Introduction

The doctrine of the Trinity is the most central one to Christian theology. When Paul writes to the Philippians and prays that the Church may be able to discern the things that are excellent (1:9-10), one of the first doctrines that would arise in the mind of any true Christian is the doctrine of the Trinity. This doctrine, along with the doctrine of divine revelation, is the main premise from which all theology proceeds. Looking at the historic Calvinist tradition, one notices that the Belgic Confession commences with the doctrine of God in its first article, followed by the doctrine of revelation in articles 2-7, before returning to the doctrine of God, and the doctrine of the Trinity in particular, in article 8.1 The Westminster Confession of Faith begins with the doctrine of special revelation in chapter 1, followed by the doctrine of God and the Holy Trinity in its second chapter.2 While the two differ slightly in their ordering, it is evident that the Reformers viewed orthodox knowledge of the essence of God and of His revelation to us as the chief premises. In the Lutheran tradition also, the doctrine of God is granted the chief place among all in the ordering of the Augsburg Confession.3

The Witness of Scripture

The doctrine of the Trinity can be derived from various texts in Scripture, the first of which is Genesis 1:26,4 to which we will return in the second part of this series. Other passages in support of this doctrine include Gen. 3:22; Matt. 3:17; 28:19; Luke 1:35; and II Cor. 13:14.

The most explicit reference to the Trinity in Scripture, however, is I John 5:7. Known as the Comma Johanneum, this text has been disputed over the past few centuries by textual critics in the tradition of Westcott and Hort. Their view of textual criticism, however, is suspect. These critics maintain that the oldest extant manuscripts are the closest to the original and therefore to be accepted as authoritative. While this presupposition is accepted by the overwhelming majority of Christians today, its implications are very problematic with regard to the Christian doctrine of canonicity. The Westminster Confession declares in its first chapter, paragraph IV: “The authority of the Holy Scripture, for which it ought to be believed, and obeyed, depends not upon the testimony of any man, or Church; but wholly upon God (who is truth itself) the author thereof: and therefore it is to be received, because it is the Word of God.” The confession continues to say that the Greek and Hebrew manuscripts, “being immediately inspired by God, and, by His singular care and providence, kept pure in all ages, are therefore authentical; so as, in all controversies of religion, the Church is finally to appeal unto them.”

The Church is therefore rightfully incapable of laying down the criteria for canonicity, but merely receives the Scripture (by the inward witness of the Holy Spirit) as such. As John Calvin notes, “In vain were the authority of Scripture fortified by argument, or supported by the consent of the Church, or confirmed by any other helps, if unaccompanied by an assurance higher and stronger than human judgement can give.”5 Calvin also writes concerning the reception of the Word: “The Law of Moses [although this applies to all of Scripture] has been wonderfully preserved, more by divine providence than by human care. . . . [I]t has continued in the hands of men, and has been transmitted in unbroken succession from generation to generation.”6 We see, then, that lower criticism, as applied by Westcott-Hort, errs in the same way the Roman Catholic Church errs: both unlawfully regard human judgment (whether scientific or ecclesiastical) as the determining factor for canonicity. Therefore, the reasons for doubting the Comma Johanneum on textual-critical grounds already rest on erroneous premises.

Furthermore, a myth utilized to discredit this Trinitarian clause claims that a Greek manuscript containing the text was fabricated by the Franciscan monk Froy. This allegedly occurred when Disederius Erasmus requested a manuscript with the comma, so he could be surer of the authenticity of his translations. Yet, there is no evidence in the writings of Erasmus himself that this ever happened. Furthermore, while it is true that the Greek evidence for this clause is weak, the Latin manuscripts make up for it.7 R.L. Dabney, though understandably weary of using this passage for polemical purposes against skeptics, also makes a strong argument as to why the Latin reading of this particular passage (mostly used by the Church through the ages) is to be received:

[Here] the Latin Church stands opposed to the Greek church. . . . There are strong probable grounds to conclude, that the text of the Scriptures current in the East received a mischievous modification at the hands of the famous Origen. . . . Those who are best acquainted with the history of Christian opinion know best, that Origen was the great corrupter, and the source, or at least earliest channel, of nearly all the speculative errors which plagued the church in after ages. . . . He disbelieved the full inspiration and infallibility of the Scriptures, holding that the inspired men apprehended and stated many things obscurely. . . . He expressly denied the consubstantial unity of the Persons and the proper incarnation of the Godhead—the very propositions most clearly asserted in the doctrinal various readings we have under review.8

Much more can certainly be said about this controversial passage, but for the purposes of this article, let it suffice that the author indeed receives it in faith as authentic and as the most explicit text in support of the doctrine of the Trinity.

Throughout the history of Christianity, there have been a great number of distortions of this cardinal doctrine of Trinitarian “consubstantial unity,” as Dabney calls it, but the Church has held it dear since the time of the apostles. Of these heresies, Arianism – known for its denial of the divinity and eternal existence of Christ – is probably the most famous. Another (though less familiar) heresy, which the Church has had to combat since its earliest days, has been the doctrine of Unitarianism. It is my purpose to address this heresy, specifically because it is more alive and well in the Church than most would like to admit. I will argue in the second article of this series that, given the current context, the Unitarian heresy desperately needs to be opposed through Christian and biblical polemics.

Trinitarian Unity Versus Unitarianism in the Early Church

Unitarianism finds its roots in the Monarchian heresies, which the early church had to oppose from as early as the the end of the second century A.D. Theodotus the leather-dealer, who came from Byzantium to Rome at the end of the second century, was the first known advocate of what became known as Monarchianism. He was most probably influenced by the Alogians in Asia Minor, and he taught that Jesus was merely a human, not eternally divine, and that He only received the powers to fulfill His office at His baptism after having proven Himself worthy. Therefore, Christ’s divine power is only communicated to Him externally, not inherent to His Person. This doctrine is known as Dynamic Monarchianism. Paulus of Samosata further developed Dynamic Monarchianism in the following century, arguing that when the Sophia or the Logos can be distinguished in God, they are merely attributes. The Father, Son, and Spirit are, then, merely impersonal powers, not different persons.

A fraternal heresy, which proved to be even more dangerous, would be Modalistic Monarchianism. This doctrine also arose in Asia Minor and, from there, spread to Rome. It teaches that Christ is simply the Father incarnate, and therefore merely a mode (modus) of the Godhead. Its first known proponent was Noetius, who was excommunicated from the Church around 230. The Noetians are famous for arguing that if Christ is God, He must be the Father, for if He is not the Father, then He is not God. By the time of the Council of Nicaea, all these heresies were comprehended under the term “Sabellianism.” The third-century theologian Sabellius principally taught that the Father, Son, and Spirit are merely three distinct names, but only one person. He also taught that God was not the Father, Son, and Spirit at the same time, but had been active under three successive forms of energy.9

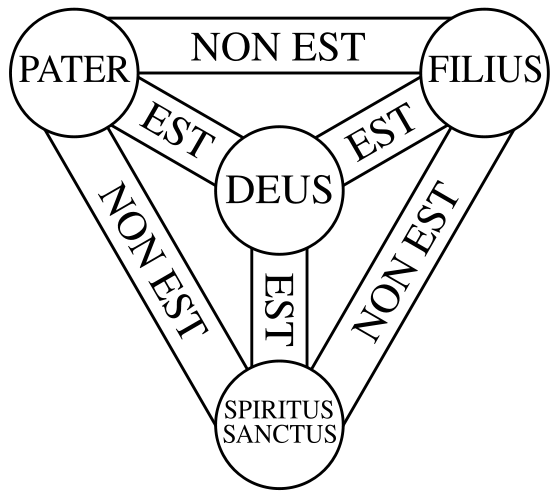

Because of the controversy caused by these early forms of Unitarianism, the Council of Nicaea convened in 325. Here the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity, delivered down from the apostles, was defended against all heresies, with Athanasius being the foremost defender of orthodoxy at the time. The council, convened by Emperor Constantine, adopted the Nicene Creed, the first orthodox creed accepted universally by the Church. The Greek word chosen to describe the unity-in-diversity of the Persons within the Trinity was ὁμοουσιος (homoousios), literally meaning “of the same substance or being,” and therefore equally God.10 (This term opposed the similar but contrary concept of ὁμοιουσιος (homoiousios), which means “of a similar substance.”) This creed, along with the Athanasian creed, clearly set forth the orthodox doctrine of consubstantial unity in the Triune Godhead. This work of God through the early church fathers, and especially Athanasius, also laid the foundation for the Westminster Divines to eventually summarize the doctrine with these words: “In the unity of the Godhead there be three Persons of one substance, power, and eternity: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost. The Father is of none, neither begotten nor proceeding; the Son is eternally begotten of the Father; the Holy Ghost eternally proceeding from the Father and the Son.”11

Conclusion

It is clear then, that Biblical Christianity confesses within the Godhead both unity and diversity. God is both one and many, as had been clearly established both by the infallible witness of Scripture and by the early Church. The heretical Unitarian heresy would, however, continue to be professed by various sects throughout history, of which the best known example in recent history is probably the Unitarian Universalist Churches. In the second article of this series, however, I intend to point out that, despite the clear witness of Scripture and the admirable work of the orthodox church fathers, the views accompanying this erroneous concept of God are more widespread than some might think, since even the contemporary mainstream Church, by embracing both alienism and egalitarianism, implicitly represents the Unitarian view of God.

Read Part 2: The Imago Dei

Footnotes

- http://www.reformed.org/documents/index.html?mainframe=http://www.reformed.org/documents/BelgicConfession.html ↩

- http://www.reformed.org/documents/wcf_with_proofs/ ↩

- http://bookofconcord.org/augsburgconfession.php#article1 ↩

- However, Gen. 1:2 alludes to the Holy Spirit. ↩

- John Calvin, The Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559), 1.8.1. ↩

- John Calvin, The Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559), 1.8.9. ↩

- http://www.thescripturealone.com/TOTT52%20(11-09)%20–%201%20John%205.7%E2%80%938%20-%20Beyond%20a%20Reasonable%20Doubt.pdf ↩

- R. L. Dabney, Discursions of Robert Lewis Dabney, biographical sketch by B. B. Warfield, 2 vols. (Carlisle, PA, USA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1967), pp. 381-382 ↩

- http://www.earlychurch.org.uk/monarch.php ↩

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homoousian#Adoption_of_the_term_in_the_Nicene_Creed ↩

- Westminster Confession of Faith, 2.III ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|