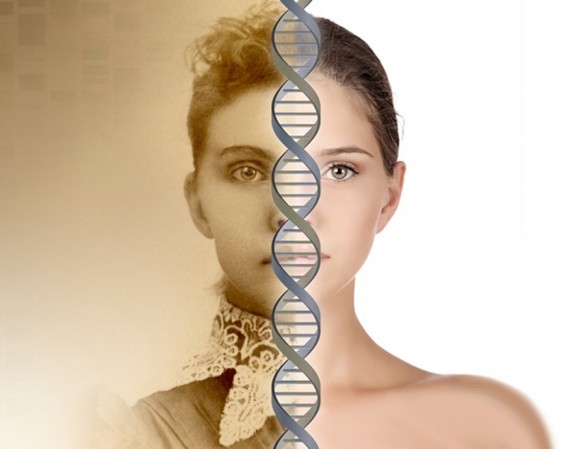

There was a fascinating article published last week discussing the work over the past two decades of molecular biologist/geneticist Szyf and neurobiologist Meaney in the field of epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression which do not alter the underlying DNA. One of these processes, and the one these two scientists focused on, are methyl groups. Not only are methyl groups modified throughout a person’s entire life, not just during fetal development as was originally believed, but Szyf and Meaney’s experiments proved that these methyl groups are inheritable and persist through generations.

The methyl groups could become married permanently to the DNA, getting replicated right along with it through a hundred generations. As in any good marriage, moreover, the attachment of the methyl groups significantly altered the behavior of whichever gene they wed, inhibiting its transcription, much like a jealous spouse….. Consider what that means: Without a mutation to the DNA code itself, the attached methyl groups cause long-term, heritable change in gene function.

This revelation was based on a series of experiments involving comparing rats born to nurturing mothers versus rats born to non-nurturing mothers. You can read the scientific details in the article itself, but the bottomline was that:

Meaney and Szyf had proved something incredible. Call it postnatal inheritance: With no changes to their genetic code, the baby rats nonetheless gained genetic attachments due solely to their upbringing — epigenetic additions of methyl groups sticking like umbrellas out the elevator doors of their histones, gumming up the works and altering the function of the brain.

They then moved on to human experiments, for example, comparing blood samples taken from English men in 1958. These experiments supported their findings with rats.

All the men had been at a socioeconomic extreme, either very rich or very poor, at some point in their lives ranging from early childhood to mid-adulthood. In all, Szyf analyzed the methylation state of about 20,000 genes. Of these, 6,176 genes varied significantly based on poverty or wealth. Most striking, however, was the finding that genes were more than twice as likely to show methylation changes based on family income during early childhood versus economic status as adults.

Timing, in other words, matters. Your parents winning the lottery or going bankrupt when you’re 2 years old will likely affect the epigenome of your brain, and your resulting emotional tendencies, far more strongly than whatever fortune finds you in middle age.

And again in a study of Russian children.

Last year, Szyf and researchers from Yale University published another study of human blood samples, comparing 14 children raised in Russian orphanages with 14 other Russian children raised by their biological parents. They found far more methylation in the orphans’ genes, including many that play an important role in neural communication and brain development and function.

This of course has lead to a change in the scope of what science considers inheritable.

According to the new insights of behavioral epigenetics, traumatic experiences in our past, or in our recent ancestors’ past, leave molecular scars adhering to our DNA. Jews whose great-grandparents were chased from their Russian shtetls; Chinese whose grandparents lived through the ravages of the Cultural Revolution; young immigrants from Africa whose parents survived massacres; adults of every ethnicity who grew up with alcoholic or abusive parents — all carry with them more than just memories.

Like silt deposited on the cogs of a finely tuned machine after the seawater of a tsunami recedes, our experiences, and those of our forebears, are never gone, even if they have been forgotten. They become a part of us, a molecular residue holding fast to our genetic scaffolding. The DNA remains the same, but psychological and behavioral tendencies are inherited. You might have inherited not just your grandmother’s knobby knees, but also her predisposition toward depression caused by the neglect she suffered as a newborn.

But not just bad experiences effect epigenetics, of course.

If your grandmother was adopted by nurturing parents, you might be enjoying the boost she received thanks to their love and support. The mechanisms of behavioral epigenetics underlie not only deficits and weaknesses but strengths and resiliencies, too.

I’ve always found the notion taught by modern “Christianity” that the only things we inherit from our parents are our fundamental sinful nature, our relatively superficial physical appearance, and nothing in-between, to be rather silly. If Adam and Eve’s fallen nature could be passed down generation to generation for over 7,000 years, then why wouldn’t the imprint of ancestral memories and experiences from a mere couple hundred or more years ago be passed down as well? But I always chalked this up to something spiritual rather than genetic, since such things don’t change DNA. However our expanding understanding of epigenetic processes like methyl groups gives a physical genetic means by which this could occur. Now to reassure the romantic nationalists like my friend Scott Terry, I still believe that there is an aspect of this that is spiritual and will never be quantifiable, however it is nice to have at least some material evidence as well to corroborate.

Now Szyf is a member of the Tribe, so that explains why these experiments were allowed to happen, why the experiments were so narrow in scope, and why there are so few applications of these insights other than pharmaceuticals. So I’ll lay out a few things I think are valid take-aways from this broadening of our understanding of epigentics.

1) Like I said above, these experiments are very narrow in scope; only looking at the effects such things as poverty have on the individual. I would bet that because the members of an ethnicity have similar ancestral experiences, these methyl group changes would be similar across the members of an ethnicity and markedly different from members of other ethnic groups. This would only be following the pattern we see in the rest of genetics. There are many ethnicity-wide personality traits that are stereotypically considered valid and are the basis for ethnic jokes – Irish are bellicose, Scots are stingy, English are reserved – could epigenetics help explain and give credence to these?

2) This is yet another torpedo into the side of the discredited “we are all just blank slates” and “race is just skin deep” ideologies. This is just another reason why transracial adoption is a very bad idea; you’re not just bringing little Samba or Chang into your house, you’re bringing their entire ancestry with them – ancestral traditions which do not mesh well with Western Civilization at all. And with interracial marriage not only are two different people being joined, but two very different ancestral epigenetics. Monoracial children only have to deal with a set of similar ancestral baggage, while biracial children have to deal with two completely different sets. No wonder interracial marriages have such a high divorce rate and biracial children have such crippling issues with identity and behavioral problems.

3) Unlike some pagan white nationalists, we are not genetic determinists. Our DNA and epigenetics give us our baseline and proclivities, but they are not the Norns setting us a path we must follow. We can overcome our negative proclivities by the grace of God and our good actions in this generation can ameliorate in future generations the bad epigenetics we inherited from past generations.

4) Note that the experiments specifically showed that epigenetic changes were most powerful in the early years of life and that positive contact with biological parents was a key to this. The old adage that a woman’s most important job is to be a mother is true even on a genetic level. All those feminist grrrl power moms who let their children be raised by daycare workers because they want to work like a man are not only screwing up their children, they’re screwing up their great-grandchildren.

5) The article ends with this question:

The question arises: Why can’t we just take a drug to rinse away the unwanted methyl groups like a bar of epigenetic Irish Spring?

The hunt is on. Giant pharmaceutical and smaller biotech firms are searching for epigenetic compounds to boost learning and memory. It has been lost on no one that epigenetic medications might succeed in treating depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder where today’s psychiatric drugs have failed.

But it is going to be a leap. How could we be sure that epigenetic drugs would scrub clean only the dangerous marks, leaving beneficial — perhaps essential — methyl groups intact? And what if we could create a pill potent enough to wipe clean the epigenetic slate of all that history wrote? If such a pill could free the genes within your brain of the epigenetic detritus left by all the wars, the rapes, the abandonments and cheated childhoods of your ancestors, would you take it?

My question is this; and if you took that pill, would you really still be you?

| Tweet |

|

|

|