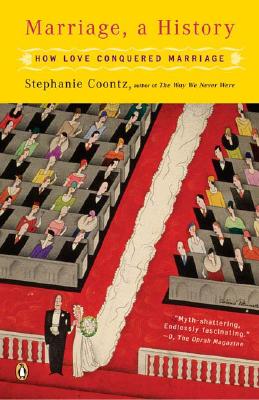

Hunter Wallace over at Occidental Dissent posted a fascinating review of Stephanie Coontz’s book, Marriage, a History. Coontz is a feminist, but in her honest chronicling of what she considers positive changes, we can see the roots of the breakdown of marriage. Predictably, the rot originates in the ill-named Enlightenment, resulting in the gradual transition from the mid-1700s to the mid-1900s of marriage from the traditional, patriarchal, community- and economy-based institution to the modern, egalitarian, individual, love-based institution. This came to full flower in the 1960s with no-fault divorce, abortion, and miscegenation all becoming fully legalized in the West. The present-day agitation for sodomy and polyamory to be recognized as marriages is just another step along the road on which love-based marriage has set us.

Hunter Wallace over at Occidental Dissent posted a fascinating review of Stephanie Coontz’s book, Marriage, a History. Coontz is a feminist, but in her honest chronicling of what she considers positive changes, we can see the roots of the breakdown of marriage. Predictably, the rot originates in the ill-named Enlightenment, resulting in the gradual transition from the mid-1700s to the mid-1900s of marriage from the traditional, patriarchal, community- and economy-based institution to the modern, egalitarian, individual, love-based institution. This came to full flower in the 1960s with no-fault divorce, abortion, and miscegenation all becoming fully legalized in the West. The present-day agitation for sodomy and polyamory to be recognized as marriages is just another step along the road on which love-based marriage has set us.

Love-based marriages are a horrible idea and entirely without support in Scripture. This is not to say that marriages should not include romantic love – they most certainly should – but holding up romantic love as the sole and necessary means of spouse-selection and marital vitality is completely without precedent in human history prior to the twentieth century. By taking biblical law, parental authority, and the community out of the mate-selection process, the West flung the doors wide open to all manner of anti-social immoral behaviors such as the interracial, sodomitic, and polyamorous unions we are seeing today. How many times have you seen such behaviors and choices defended on the basis of “love”? And if “love” is the only thing of importance, why get married at all? One can experience the full range of romantic love outside of marriage. The idea of love-based marriage leads to the very dissolution of the whole marital institution.

The conservative prophecies warning against the results of changes to the basis and definition of marriage have been accurate for almost three centuries now.

During the eighteenth century the spread of the market economy and the advent of the Enlightenment wrought profound changes in record time. By the end of the 1700s personal choice of partners had replaced arranged marriage as a social ideal, and individuals were encouraged to marry for love. For the first time in five thousand years, marriage came to be seen as a private relationship between two individuals rather than one link in a larger system of political and economic alliances. . . .

Especially momentous for relations between husband and wife was the weakening of the political model upon which marriage had long been based. Until the late seventeenth century the family was thought of as a miniature monarchy, with the husband king over his dependents. As long as political absolutism remained unchallenged in society as a whole, so did the hierarchy of traditional marriage. But the new political ideas fostered by the Glorious Revolution in England in 1688 and the even more far-reaching revolutions in America and France in the last quarter of the eighteenth century dealt a series of cataclysmic blows to the traditional justification for patriarchal authority. . . .

The people who pioneered the new ideas about love and marriage were not, by and large, trying to create anything like the egalitarian partnerships that modern Westerners associate with companionship, intimacy, and “true love.” Their aim was to make marriage more secure by getting rid of the cynicism that accompanied mercenary marriage and encouraging couples to place each other first in their affections and loyalties.

But basing marriage on love and companionship represented a break with thousands of years of tradition. Many contemporaries immediately recognized the danger this entailed. They worried that the unprecedented idea of basing marriage on love would produce rampant individualism.

Critics of the love match argued – prematurely, as it turned out, but correctly – that the values of free choice and egalitarianism could easily spin out of control. If the choice of a marriage partner was a personal decision, conservatives asked, what would prevent young people, especially women, from choosing unwisely? If people were encouraged to expect marriage to be the best and happiest experience of their lives, what would hold a marriage together if things went “for worse” rather than “for better”?

If wives and husbands were intimates, wouldn’t women demand to share decisions equally? If women possessed the same faculties of reason as men, why would they confine themselves to domesticity? Would men still financially support women and children if they lost control over their wives’ and children’s labor and could not even discipline them properly? If parents, church, and state no longer dictated people’s private lives, how could society make sure the right people married and had children or stop the wrong ones from doing so?

Conservatives warned that “the pursuit of happiness,” claimed as a right in the American Declaration of Independence, would undermine the social and moral order.

| Tweet |

|

|

|