THE FIRST WORD

THE SECOND WORD

THE THIRD WORD

THE FOURTH WORD

THE FIFTH WORD

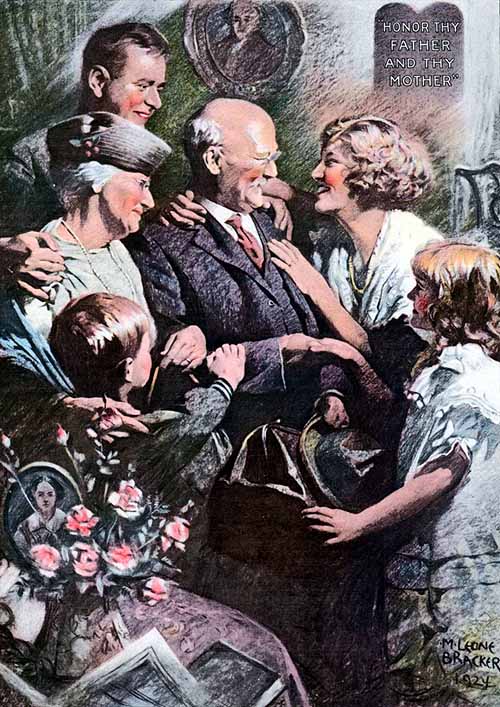

Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.

The Catechism summarizes the scope of this law as enjoining “the performance of those duties which we mutually owe in our several relations, as inferiors, superiors, or equals.”1 Which is to say that this commandment exemplifies hierarchy, and cannot be understood apart therefrom. The included acknowledgment that the law here connotes varied duties ‘to our several relations’ patently condemns the New Age ethical abstraction of ‘fairness’ which touts ‘treating everyone equally’ as a sublime virtue. Social egalitarianism is denounced, then, by the fifth law as Gnostic myth.

Assuming the egalitarian presuppositions of the Neo-Theonomists, who have come to lobby for a nuclear family based not upon any physical relation, but upon contract and cohabitation, the most that can be deduced from this annexation of promise to live ‘long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee’ is a singular, personal length of days on one’s parcel. But this interpretation, as we know, is at loggerheads with the express national context of the covenant, which is redundantly set before Israel, reminding them that the Covenant hallows not just their immediate domiciles and immediate family, but the span of their generations, preceding and proceeding: “Behold, I have set the land before you: go in and possess the land which the Lord sware unto your fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to give unto them and to their seed after them” (Deut. 1:8).

No, the inducement of the fifth word, delivered as it is in the context of the national Covenant upon promises made to remote ancestors, ensures the inheritance of the land (in conjunction with the promise of the second law) ‘to a thousand generations’ (Ex. 20:6): a promise of covenant legacy and national preservation. So did centenarian Faeroese patriarch, Graekaris Madsen, explain the fifth law:

My grandfather taught me to read and write and to obey the laws of God. He said, ‘Honor thy father and thy mother, and all the ancestors from the very first to have settled here, and you will live long in the country.’ That’s what I’ve tried to do.2

After all, if we are bound all our lives to honor father and mother, as they were likewise enjoined to honor their fathers and mothers, then we cannot avoid the implication of honoring those to whom our parents were likewise duty-bound to honor; in order to rightly esteem our father and mother, we are necessarily impelled to honor theirs, and those before them. And that with an eye toward the promise redounding to our own posterity in generations forthcoming.

Who could really imagine it otherwise? How could a child especially honor his father if he treated his father’s father as a stranger? Clearly, the fifth law is a call to special love of one’s ancestors for the sake of one’s descendants as joint partakers, a lineage hallowed to God. Few relationships lay the reciprocity of the Golden Rule before our eyes in such stark relief as when we treat our sires as we wish to be treated by our sons.

Underlying this, however, we find that the codification of familialism-on-nationalism here is not the standalone objective, as St. Paul discloses the divine rationale behind the existence of the nations He “hath made of one blood all nations [ethne] of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth . . . That they should seek the Lord, if haply they might feel after Him, and find Him” (Acts 17:26-27). Which is to say that the normative life order for mankind, as decreed by God, is ethnonationalism; and that, for the purpose of fostering true religion. As Paul explains, the relative social insularity of ethnic enclaves engenders a certain perspectivalism without which genuine religion does not flourish. The words of S.H. Kellogg are here illuminating:

If we are surprised, at first, to see this place of honour in the law of holiness given to the fifth commandment, our surprise will lessen when we remember how, taking the individual in the development of his personal life, he learns to fear God, first of all, through fearing and honouring his parents. In the earliest beginnings of life, the parent – to speak with reverence – stands to his child, in a very peculiar sense, for and in the place of God. We gain the conception of the Father in heaven first from our experience of fatherhood on earth; and so it may be said of this commandment, in a sense in which it cannot be said of any other, that it is the foundation of all religion. Alas for the child who contemns the instruction of his father and the command of his mother! for by so doing he puts himself out of the possibility of coming into the knowledge and experience of the Fatherhood of God.3

The Fatherhood of God is made accessible to the minds of men by the analogy which precedes it in our natural experience – our apprehension of physical fatherhood. Likewise, then, with spiritual brotherhood: it is preceded and made comprehensible by physical brotherhood, and the motherhood of the Church by acquaintance with our own mothers. As is our sense of solidarity in the spiritual tribe and nation of our Christian creeds made significant through the covenantal apparatus of physical peoplehood. The abiding sanctity of kinship is the epistemological emissary of all spiritual relations in the Kingdom of God. We do not truly comprehend one without the other. We dare not dismiss the physicality of our being as invalid or immoral, for to dismiss either the physical or the spiritual is to lose the meaningfulness of both. This, therefore, is the reason why the Christian faith, historically, and in the fabric of biblical law, underscores the sanctity of kinship so – because these tropes are the chosen and necessary means of God to foster true morality and religion amongst the sons of men.

Our existence as ‘sons of Abraham’ in the ‘spiritual nation of Israel’ is an incomprehensible abstraction aside from the forerunning virtues of sonship under our own patriarchs in our physical nations. Regeneration relies upon natural generation for its basic context. And if the thing analogized be wholesome and true, that by which it is analogized cannot be otherwise: if the spiritual peoplehood of Christians is good, then so too must our foregoing physical peoplehood be good.

Aside from these realities, we cannot rightly understand the fifth law.

THE SIXTH WORD

Footnotes

- Westminster Larger Catechism, question #126 ↩

- La Fay’s 1972 interview with Graekaris Madsen, The Vikings, p. 119, emphasis mine ↩

- S.H. Kellogg, The Expositor’s Bible: The Book of Leviticus, Chapter XXI ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|