If you’re like me, you find yourself getting angry on a regular basis. Seemingly every time I read news headlines I find my fists clenched in anger at what is going on in our world. I’m angry about the rampant crime suffered by whites at the hands of non-whites, and I’m made even angrier that these stories are obscured and concealed by the mainstream media. I’m angry at the corruption in our government at every level. I’m angry at the moral degeneracy that has deluged Western civilization over the past several decades. What particularly infuriates me is the response that most professed Christians have to these problems. When these important topics are brought up in conversation most Christians range somewhere from completely oblivious to overtly hostile. It seems that Christians aren’t merely ignorant of the moral decay of our society, but in many cases are complicit in this evil. We’ve all had experiences of being told not to judge anyone based upon Jesus’ thoroughly abused statement in the Sermon on the Mount, “judge not, that ye be not judged” (Matt. 7:1). I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve heard professed Christians state that Jesus’ primary message was of “love, acceptance, and tolerance,” or something along those lines.

The error persists in the modern church that anger and hatred are intrinsically wrong, and that we should never judge the actions of others because only God can judge. This thinking demonstrates a complete ignorance of what the Bible actually teaches about anger, hatred, and judgment. The Bible does condemn unjust anger and hatred along with false judgment in many instances,1 but also establishes the existence of righteous anger, hatred, and judgment. God is repeatedly said to be angry with rebellious sinners (Ps. 7:11). Jesus becomes angry at the people’s stubbornness (Mk. 3:5). Jesus’ anger is vividly demonstrated when he beat the money changers and drove them from the Temple (Matt. 21:12-13, Mk. 11:15-18, Lk. 19: 45-46, Jn. 2:13-25).2 Nehemiah is similarly angered by the betrayal of his countrymen when they married foreign wives (Neh. 13:23-31). The prophet and judge Samuel provides an example of righteous anger and how it manifests in action. The Israelites under King Saul had been tasked with destroying the Amalekites because of their persistent injustices committed against the Israelites. King Saul fails to kill Agag, the King of the Amalekites, and Agag appeals to Samuel suggesting that the bitterness of death has passed. Samuel does not respond with mercy, because what Agag has done to others has merited his own death. Samuel cuts Agag into pieces, motivated by love and justice for all the mothers whom Agag had victimized (1 Sam. 15:8-33).

This kind of righteous anger is not merely permitted or allowed but is a necessary response to evil. The Bible explicitly commands the hatred of evil as a natural extension of the love for good (Ps. 97:10, Prov. 8:13, Amos 5:15). A lack of righteous anger is not evidence of pious detachment from the problems of the world, but rather a lack of zeal for truth and justice. The Apostle Paul castigates the church of Corinth for their practice of taking Christian brothers before the secular courts without judging these matters themselves (1 Cor. 6:1-11).3 This demonstrates that the apostolic understanding of Jesus’ teaching to “judge not, lest ye be judged” is not to refrain from any judgement whatsoever. This is impossible, as judging someone for being “too judgmental” is a judgment in and of itself. Jesus makes it clear that he was condemning hypocritical judgment. This is lost on many modern Christians who are completely ignorant of Jesus’ many judgments against the Pharisees and Sadducees recorded in the Gospels. Jesus makes it perfectly clear that the apostles are to judge righteously rather than superficially (Jn. 7:24).

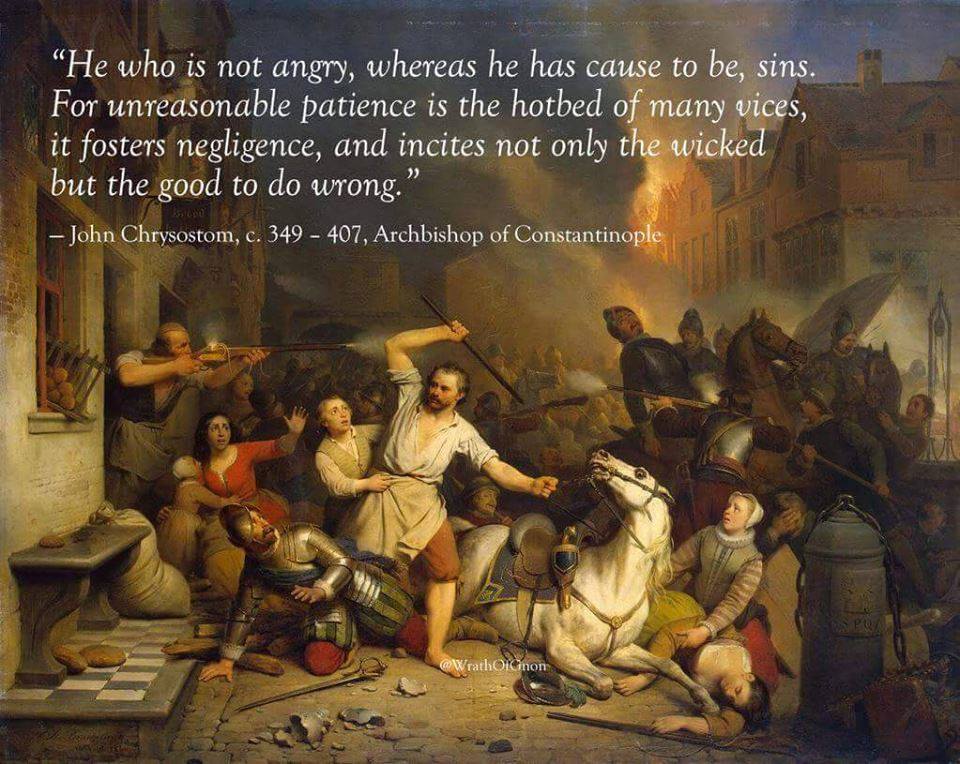

Eminent theologians in all ages of Church history have understood the important place of righteous anger. John Chrysostom stated,

Only the person who becomes irate without reason, sins. Whoever becomes irate for a just reason is not guilty. Because, if ire were lacking, the science of God would not progress, judgments would not be sound, and crimes would not be repressed. Further, the person who does not become irate when he has cause to be, sins. For an unreasonable patience is the hotbed of many vices: it fosters negligence, and stimulates not only the wicked, but above all the good, to do wrong.4

Thomas Aquinas also explained the proper place of righteous anger in the Christian life:

Ire may be understood in two ways. In one way, as a simple movement of the will that inflicts punishment not through passion, but by virtue of a judgment of the reason: and in this case, without a doubt, lack of ire is a sin. This is how Chrysostom understands ire when he says: ‘Ire, when it has a cause, is not ire but judgment. For properly speaking, ire is a movement of passion. And when a man is irate with just cause, his ire does not derive from passion. Rather, it is an act of judgment, not of ire.” In another way, ire can be understood as a movement of the sensitive appetite agitated by passion with bodily excitation. This movement is a necessary sequel in man to the previous movement of his will, since the lower appetite naturally follows the movement of the higher appetite unless some obstacle prevents it. Hence the movement of ire in the sensitive appetite cannot be lacking altogether, unless the movement of the will is altogether lacking or weak. Consequently, the lack of the passion of ire is also a vice, as it is the lack of movement in the will to punish according to the judgment of reason.”5

Finally, Charles Spurgeon speaks to the necessity of righteous anger: “A vigorous temper is not altogether an evil. Men who are as easy as an old shoe are generally of as little worth.”6

King David provides us with an excellent example of how judgment against sin and sinners ought to follow from our zeal for personal holiness. David states that God will surely slay the wicked that speak against Him and take His name in vain. David states that he hates those who hate God, and he counts them as his enemies (Ps. 139:19-22). This righteous anger and hatred towards those who hate God is rooted in God’s own hatred for the wicked (Lev. 20:23 and Ps. 5:4-6, 7:11). The righteous zeal expressed by King David is grounded in a love of God’s law as God’s perfect standard of righteousness (Ps. 1:2, 19:7, 94:12, and Ps. 119). David’s hatred of evil prompts him to examine himself and purge evil out of his own life (Ps. 139:23-24). Likewise, the anger that we experience at the injustices in our world should primarily motivate us to banish sinful habits from ourselves first. In this way we follow Jesus’ teaching by removing the logs from our own eyes, so that we can remove the specks from our neighbors (Matt. 7:2-5). In this way we also avoid the hypocritical judgment that Christ condemned. Secondly, we must make sure that our righteous anger does not spill over into sinful anger and hatred. I find that I can at times direct even righteous anger at an innocent target. Anger should always be directed at those who have merited it by their actions. By experiencing and harnessing righteous anger, we can play a small role in awaking lethargic Christians from their moral slumber and making a real and lasting change in our world.

For more on the topic of righteous anger and hatred, see the Rev. John Weaver’s excellent sermon: “The Biblical Doctrine of Hatred.” Also see Nil Desperandum’s “Biblical Love and Hatred Harmonized.”

Footnotes

- For example see Matt. 5:22, Eph. 4:31, Col. 3:8, Jas. 1:19-20, etc. ↩

- As an aside, I take the view that the incident recorded in John’s Gospel is distinct from the incident recorded in the three synoptic Gospels. The details are different enough, and it seems that the most natural explanation is that John is recording something that happened at a Passover near the beginning of Jesus’ public ministry while the synoptic Gospels record an incident that occurred after Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem before his final Passover. ↩

- In Paul’s second epistle he praises the Corinthians’ repentance which led to their “indignation,” “vehement desire,” “zeal,” and even “revenge” or “punishment.” ↩

- Homily XI super Matheum, 1c, nt.7 ↩

- Summa Theologiae, II, II, q. 158, art. 8. Both quotes from Chrysostom and Aquinas are featured on the Tradition in Action post titled, “One Sins By Not Becoming Duly Irate.” ↩

- Charles Haddon Spurgeon, Lectures to My Students ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|