Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Part 7

Part 8

Part 9

Part 10

Part 11

Chapter 26, Of the Communion of the Saints, says “being united to one another in love, they have communion in each other’s gifts and graces, and are obliged to the performance of such duties, public and private, as to conduce to their mutual good, both in the inward and outward man. (WCF 26:1)

The Alienist imputes to any mention of unity a mandate of borderless metropolitanism banning all distinction, so they take passages such as this as their vindication. But a careful reading of it in abeyance of modern assumptions tenders a precisely opposite doctrine.

Scripturally speaking, being ‘united in love’ nowhere abrogates distinction — no more between man and wife than between the members of the Godhead. For their unity and diversity are co-ultimates. This view which Alienists now profess not to recognize is simply the trinitarian view. And the only basis of coherence itself. The alternative, which the Old School Presbyterians referred to as ‘social Unitarianism’, would more precisely be identified by T. Robert Ingram as monism. According to the general definitions, “Substance monism is the philosophical view that a variety of existing things can be explained in terms of a single reality or substance.” That is, monism is characterized by the obfuscation of particulars and lesser categories by reference to some commonality between them: “because mankind is come of a monogenesis, any demarcation between Chinese and Swedes is illusion, a lie, and sin.” This is precisely the position of our neo-churchmen on the issue of unity in both the Church and mankind at large.

But note the stipulation of an obligation to use our variegated ‘gifts and graces’ to ‘their mutual good’. Acknowledgement of that unequal apportionment of graces is itself to confess inequality ordained of God.

As much as Alienists rue it, good for the inward (spiritual) and outward (physical) man “according to their several abilities and necessities” (WCF 26:2) demands divisions between families, nations, and races. Because those social bulkheads are among the ‘necessities’ which nurture ‘their several abilities’. And failing to maintain those demarcations is to unleash anarchy in principle and violence in fact. Doctrinally speaking, familism is necessary to the basic sustentation of the family; so too nationalism to the nation; as is some degree of segregation to the livelihood of the race. And each proves concursive with the last, as few things prove so deleterious to the solidarity of family life as a multicult environment. And nothing promotes strife, theft, oppression, rapine, and murder more than surpassing the lawful bounds of our ethnos — a thing which, according to Calvin’s commentary on Acts 17, occurs only as the fruit of “wicked lust” intent on “the overthrow of God’s providence.”

Accordingly, the divines conclude the chapter with these words: “The communion which the saints have with Christ, doth not make them in anywise . . . equal with Christ in any respect. . . . Nor doth their communion one with another, as saints, take away, or infringe the title or propriety which each man hath in his goods and possessions.” (WCF 26:3)

Incoherent as it is, it has become a default assertion on the part of liberals to say that our unity in Christ makes all men equal. But this does precisely what the confession disallows, as proclaiming equality of all men in one is arithmetically to declare equality with that one — in this case, Jesus. The Alienist may dissemble on the issue, but if they claim unity in Christ makes men equal, that unitary identity is inescapably a claim of equality with Christ. To which the fathers say, anathema.

This segment also speaks to the matter of private properties, as well as personal properties which are not entirely private. For God has made us each custodians to more than our private real estate holdings. We are custodians of our inherited language, culture, community, civilization, and respective folk. We are responsible not just for what happens within the walls of our homes, but in our streets. Because they are, in the communal sense, ours. If not, one could not speak of his community, culture, tribe, nation, or people. But we all do. And we all therefore acknowledge these among the properties, goods, and possessions of men; and these are wrongly taken from us by the error of Alienism.

Truth be told, short of taking their lives directly, there is no act so holistically larcenous as taking someone’s peoplehood from them. For when your country is no longer the country of your people, you have lost all that makes it your home. As the English are learning presently, an England overrun with Pakistanis and Africans is no longer England. Because the Anglo-Saxon can perceive nothing in the influx of such disparate elements but the loss of all that he loves; and that, supplanted by antipodes bent on the erasure of all vestiges of English culture and folk.

As it turns out, even under circumstance of a shared faith and race, the English divines found in their collaboration with the Scots that “the adoption of purely Scottish forms by both nations was not to be hoped for.” (Warfield, The Westminster Assembly and Its Work, p. 29) Because the English had areas of wholesome divergence from Scottish anchored in their own folk and folkways. And even if the English and Irish confessed the consequent superiority of the Scottish church, and adopted the same confession, they simply could not identify wholly with Scottish worship and custom.

They harbored no Alienist delusions of uniform culture or borderless Babelism within the Church. In fact, they spurned any such blurring of national jurisdiction and identity hotly:

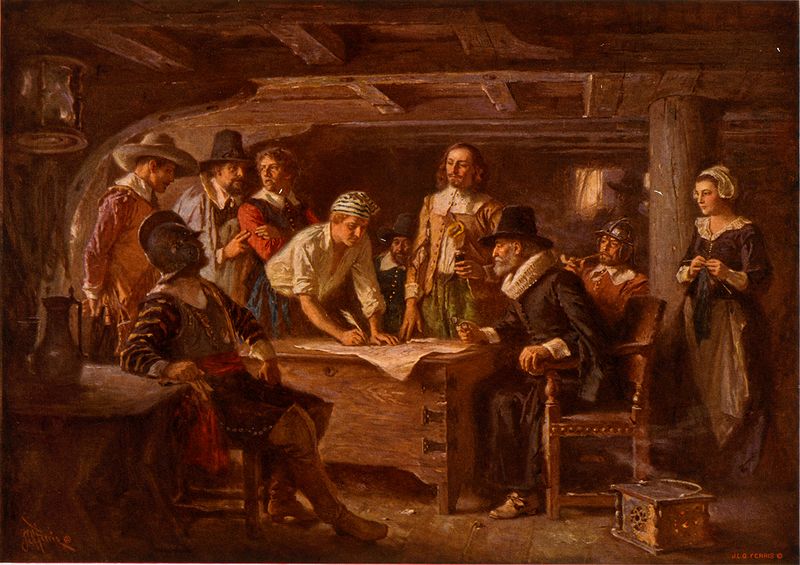

The Solemn League and Covenant, it must be borne in mind, was no loose agreement between two Churches, but a solemnly ratified treaty between two nations. The Commissioners who went up to London from Scotland under its provisions, went up not as delegates from the Scottish Church to lend their hand to the work of the assembly of Divines, but as the accredited representatives of the Scottish people … [for the sake of] religious uniformity which the two nations had agreed with one another to institute. (Warfield, ibid., p. 31)

This ardent nationalism was further buttressed by their anti-egalitarian convictions:

A disposition manifested itself . . . to look upon them merely as Scotch members of the Assembly of Divines, appointed to sit with the Divines in response to to a request from the English Parliament. This view of their functions they vigorously repudiated. They were perfectly willing, they said, to sit in the Assembly as individuals and to lend the Divines in their deliberations all the aid in their power, if the Parliament invited them to do so. But as Commissioners for their National Church, they were Treaty Commissioners, empowered to treat with the Parliament. (Warfield, ibid., p. 32-33)

Because the Scotch divines understood themselves to be advisory ambassadors representing the Scottish stock, they insisted that their roles were something apart from those of the English divines. This inequality of ethnic jurisdiction they upheld, in fact, to the point that they declined to participate in the plebiscites of the Assembly (ibid., footnote 64, p. 34). Because they were keen not to violate the principles herein which would shortly be outlined in 26th chapter of the confession.

So in chapter 29, Of the Lord’s Supper, we see the Kinist nature of the Kingdom reasserted in the “pledge of their communion with Him, and with each other, as members of His mystical body.” (WCF 29:1) That is to say, while we may enjoy sundry degrees of unity in terms of culture, geography, generation, race, etc., there is one rung of unity in which all believers share — a mystical one. The very significance of which is underscored by our lack of commonality in other ways.

And any claim that the far-flung covenanted peoples are made identical by the faith only undermines the significance of that mystical union, which is not in our totality, but by faith alone.

Read Part 13

| Tweet |

|

|

|