Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: McDurmon’s Rejection of Christendom and Embrace of Egalitarianism

Part 3: McDurmon’s Use of Sources

Joel McDurmon makes several claims about the specific abuses suffered by black Africans at the hands of white Christians. The majority of McDurmon’s book is dedicated to chronicling these abuses in order to explain the horrors of American slavery. The claims McDurmon makes are extremely tenuous. Let’s begin by examining McDurmon’s claims about the trans-Atlantic slave trade, as well as accusations of “slave breeding” in order to increase the slave population.

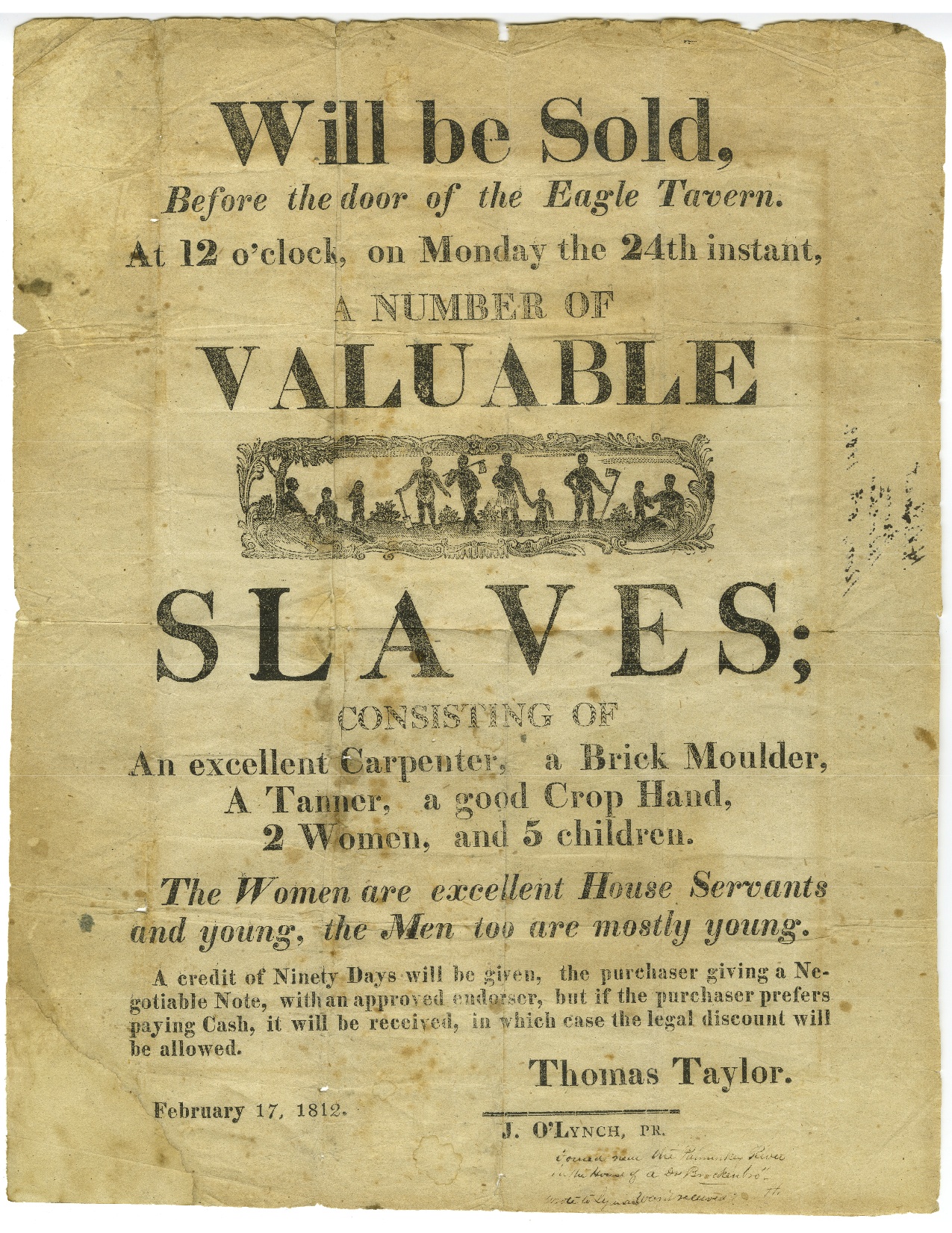

The Slave Trade

McDurmon’s anti-white animus is obvious in his portrayal of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, as he seeks to divert blame from African chieftains and assign all blame to white Europeans. During his discussion on manstealing McDurmon discusses the argument that “if we blame whites, we ought just as strongly to blame the African chieftains.”1 McDurmon responds by insisting that “although chieftains bear responsibility, they played only a facilitative role once the Portuguese started the trade. . . . This new demand was a ‘new force’ which affected areas of Africa in new ways. Prior to western involvement, slavery within these parts of Africa was largely a parochial form of social dependency. . . . The Atlantic slave trade in effect led to the creation of a vast political and social institution in Africa that was devoted to producing slaves for western consumption, which decimated entire populations, and which had not existed as such before. It was no subtle shift, but rather a ‘radical break in the history of Africa.’”2

McDurmon would have his readers believe that slavery in Africa was a benign “form of social dependency” until those nasty, evil white men arrived. Naturally whites are to receive any and all blame for whatever crimes occurred during the slave trade. Native Africans played a merely “facilitative role.” This idea is so radical that even most mainstream leftist academic sources don’t take this contention seriously. Most black Africans acknowledge the role that the native blacks played in advancing the slave trade with Europeans. White European demand for African slaves may certainly have fueled the long-existing internecine warfare of Africa, but it is asinine to assert that whites are to blame for its origin. Even PBS, which would be favorably disposed to virtually anything that casts white Christians in a bad light, has published an article detailing the deep history of slavery in Africa.

The author Zayde Antrim states,

Europeans often acted as junior partners to African rulers, merchants, and middlemen in the slave trade along the West African coast from the mid-15th century on. . . . Furthermore, when Europeans first initiated a trading relationship with West Africans in the mid-15th century they encountered well-established and highly-developed political organizations and competitive regional commercial networks. Europeans relied heavily on the African rulers and mercantile classes at whose mercy, more often than not, they gained access to the commodities they desired. European military technology was not effective enough to allow them this access by means of force on a consistent basis until the 19th century. Therefore it was most often Africans, especially those elite coastal rulers and merchants who controlled the means of coastal and river navigation, under whose authority and to whose advantage the Atlantic trade was conducted. Domestic slave ownership as well as domestic and international slave trades in western Africa preceded the late 15th-century origins of the Atlantic slave trade.

The demand for slaves was high in Africa, both among native sub-Saharan Africans and Arab Muslim slave traders. It is ridiculous to contend that the demand for slaves was fueled almost exclusively by white Europeans. The Muslim demand for slavery was incredibly high and existed both before and after the European trans-Atlantic slave trade and after the abolition of slavery in Western countries. Arab enslavement of Africans was particularly brutal in comparison to the treatment of Africans by white Europeans. The mortality rate of Africans transported across the Sahara desert by Arabic slave traders is estimated to be as much as eight or nine times the mortality rate of Africans transported across the Atlantic. To ignore the role of Arab and African slave traders is an egregiously dishonest portrayal of slavery in Africa on McDurmon’s part.

Slave Breeding

McDurmon has a section titled “The Slave Breeding Industry.” McDurmon states that “the phrase ‘breeding females’ was part of common usage” in the antebellum South.3 The primary motivation for slave breeding, according to McDurmon, was the end of the importation of slaves in 1808 which made the value of domestic slaves and their children increase. It makes sense that slave-owners would naturally want their slaves to reproduce for economic reasons, if nothing else, but does this mean that slaves were routinely forced to copulate with other slaves against their will? McDurmon alleges that slaves were routinely encouraged to breed exclusively for profit. As evidence, McDurmon cites letters that Thomas Jefferson wrote to his sons-in-law and friends about the profitability of breeding females. I reproduce these portions of the letters with McDurmon’s emphases in italics, because it is so central to his argument on this point.

The death of 5 little ones in 4 years induces me to fear that the overseers do not permit the women to devote as much time as is necessary to the care of their children: that they view their labor as the 1st object and their raising their child as but as secondary. I consider the labor of a breeding woman as no object, and that a child raised every 2 years as of more profit than the crop of the best laboring man. In this, as in all other cases, providence has made our interests and our duties coincide perfectly. . . . With respect therefore to our women and their children I must pray you to inculcate upon our overseers that it is not their labor, but their increase which is the first consideration with us.

Again the very next year, “I know no error more consuming to an estate than that of stocking farms with men almost exclusively. I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm what she produces is an addition to the capital.”4

McDurmon draws attention to similar statements to the effect that slave breeding should be encouraged because the children of slaves increased the overall value of the plantation. What do Jefferson’s statements in private conversations reveal about him or other slave-owners in general? While Jefferson was clearly motivated at least in part by profitability, this far from qualifies as “slave breeding.” Jefferson expresses a concern for the infant mortality of slave families. He states that plantation managers should allow slave women sufficient leisure to make sure that they can safely deliver and care for their offspring.

Jefferson states his belief that ideally slave women would have children every two years, which is certainly not excessive or consistent with the idea of “breeding” slaves. That Jefferson would also express an interest in the profitability of the increase of slave families is likewise sensible. Many Southern families had a good deal of wealth tied to slavery, so it is only natural that they had a financial interest in the future generations of slave families for either the future labor of these generations or, frequently, the money made by their future redemption by relatives.

Even McDurmon acknowledges that accusations of slave breeding are largely rooted in mythology. McDurmon writes, “We should quickly clarify that by ‘slave breeding,’ we do not refer to the largely mythical ‘stud farms,’ where slaveowners allegedly did nothing else than mate choice male ‘stock’ with select slave women and harvest crops of slave babies. Even the most thorough studies of the domestic trade and slave breeding admit that no such plantations existed (although a few isolated masters apparently tried).”5

McDurmon provides a purported attempt at slave breeding in Samuel Maverick. “Boston plantation owner Samuel Maverick attempted as early as 1639 to coerce a female slave to submit to impregnation by a male slave he selected. She resisted vehemently, and while the account does not clearly say that the deed never occurred, it does seem that she prevailed.”6 This incident is simply sourced to Winthrop Jordan’s White Over Black without any further primary documentation.7, p. 71.] Even this one example hardly establishes the practice of anything that could be called “slave breeding,” and the fact that the female slave in this case was able to refuse is actually proof that the prevailing opinion among whites was that blacks could not be abused at whim by slave-owners or bred as though they were cattle.

Next we’ll examine McDurmon’s claims about white-on-black rape. Amazingly McDurmon argues that it was both common and legal for white men to rape slave women. He also manages to accuse the great Robert L. Dabney of lying in his Defense of the South. Buckle your seat belts.

Read Part 5: Rape

Footnotes

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Location 9089). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 9091-9107). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. Emphasis is mine. McDurmon continues, “Slaves may have been taken in tribal warfare, or may have been subjected for economic reasons. With increased demand from foreign traders, however, slaves immediately became a valuable commodity. Warlords, sometimes armed with weapons they obtained in the trade, led raids for the express purpose of enslaving individuals for sale to Europeans. The vast majority of victims were enslaved through slave raids, kidnapping, or legal manipulations. Some substantial cases used religious deception and trickery with local oracles, but the end result was kidnapping nonetheless. . . . Slave exports rose drastically in the 1600s, then exploded in the 1700s, totaling about 6.5 million souls in that century alone. By the time the Atlantic slave trade was finally ended, it had exported 12.8 million victims. Another 12 million newly-enslaved victims never left Africa: they either died during the enslavement processes, or were simply never sold. These atrocities, after 1700, were for the most part not the result of natural native wars, but of a phenomenon that would not have taken place without the demand from the West.” McDurmon sources this to Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. 2nd Ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2000),18, 22, 23, 82–83. Lovejoy, 18, 64–65, 74. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 2685-2686). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- Thomas Jefferson to Joel Yancey, January 17, 1819; and to John Wayles Eppes, June 30, 1820; both unpublished (Massachusetts Historical Society, Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts), available at http://www.inmotion-aame.org (accessed May 18, 2017). See also Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., February 13, 1792; and to Bowling Clarke, September 21, 1792; both unpublished (Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Thomas Jefferson Papers), available at http://www.inmotion-aame.org (accessed May 18, 2017). Cited in McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 2712-2723). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. Emphasis is McDurmon’s. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 2690-2693). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 2686-2689). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- McDurmon cites Jordan, Winthrop D. White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550—1812. New York and London: W. W. Norton and Co., 1977 [1968 ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|