2017 marks 500 years since the start of the great Church Reformation by Martin Luther. In celebration thereof I will write a series of articles throughout the year relating to the Reformers’ views on race and nationhood, which will be published here on Faith and Heritage between now and October 31st.

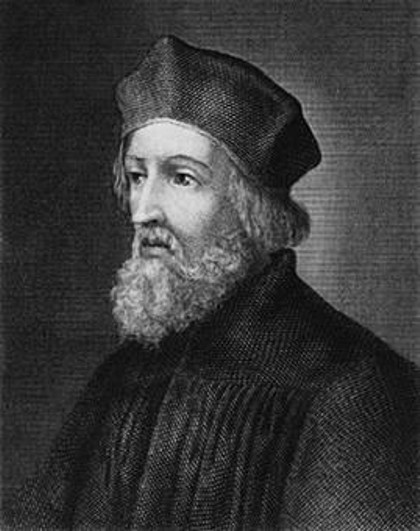

I plan on focusing in particular on relevant quotes from sixteenth-century Reformers themselves, but today I thought it appropriate to start off the series with a statement by one of the most famous proto-Reformers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, John Hus (1369-1415). This Czech theologian was a key predecessor to the Reformation in continental Europe. His God-glorifying life came to a sad end after he was convicted for heresy and burned at the stake.

Referring in a sermon to the foreign invasion of Bohemia in 1401, Hus proclaimed:

According to every law, including the law of God, and the natural order of things, Czechs in the kingdom of Bohemia should be preferred in the offices of the Czech kingdom. This is the way it is for the French in the French kingdom and for the Germans in German lands. Therefore a Czech should have authority over his own subordinates as should a German.1

Hus’s appeal to God’s law and the natural order signifies his commitment to divine revelation as supremely authoritative. This was, of course, a central doctrinal pillar upon which the Reformation stood. With this appeal to divine revelation, he argues for the principle of kin-rule (Deut. 17:15) as the ordained order by which states and governments function optimally, and the best means of achieving human flourishing. The premises underlying this statement can therefore be understood as both kinist and race-realist.

Firstly, the argument is based on the recognition of the nature of God’s created order in establishing families, clans, nations, and races distinctly and separately in order to establish fruitful human frameworks for the optimal functioning of God’s law. Natural affinities are proclaimed as good in Scripture (Romans 1:31; II. Tim. 3:3) precisely because the cultivation of these creates God-honoring societies.

Secondly, Hus recognizes that the reality of ethnic (or racial) distinctions generates counterproductive political circumstances when government and populace become multicultural. He argues for the preservation of homogeneity in the Bohemian state on the basis of the principle of the golden rule, as reality demands this as in the interest of all peoples.

Finally, his distinction of Bohemia as the land of the Czechs from the “French kingdom” and the “German lands” exemplifies his commitment to the biblical principle of one ethnicity per political unit (Acts. 17:26), in contradistinction to multiracialism and multiculturalism.

Part II: John Wycliffe on the Ethnic Homogeneity of the National Church

| Tweet |

|

|

|