Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

In the first three editions on slavery and social inequality, we saw that there was no deviation in the message taught by Christ, the prophets, and the Apostles. This should make sense to orthodox Christians, since God is the divine author of the Bible (2 Tim. 3:16) and God does not change (Jas. 1:17). This edition will deal with a last-ditch effort on the part of the abolitionists. The abolitionists argued that although the Apostles did not explicitly condemn the institution of slavery, they “girdled it up and left it to die.”

The Nature of Abolitionist Exegesis

The South Carolina Presbyterian pastor James Henley Thornwell did not mince words when he stated,

The parties in the conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders. They are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, Jacobins on the one side, and friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battleground – Christianity and Atheism the combatants; and the progress of humanity at stake.1

At first this may seem like nothing more than the heated rhetoric of an embroiled southern partisan. Further analysis, however, serves to vindicate Thornwell’s claims regarding the nature of the abolitionists. Many abolitionists of the nineteenth century, as well as Christians today, argue that while the Apostles never directly condemned slavery or servitude, they were opposed to slavery in spirit. Abolitionism was simply one in a long line of social causes that liberals pursued in the name of the social gospel. Eventually, abolitionism was followed by feminism, the women’s suffrage movement, the temperance movement, and the civil rights movement as the great pursuits of the social gospel.

It should not surprise us that those who argued in this fashion tended to be theologically liberal. Many abolitionists were Unitarians who represented the core of what remained of the New England political and religious establishment. These Unitarians had clearly abandoned orthodoxy by the time that slavery became a major political issue in the nineteenth century. Some, like Unitarian pastor Theodore Parker, even went so far as to clearly dismiss the authority of the Bible. John Brown was nominally Methodist, yet his maniacal and murderous crusade against innocent people was clearly motivated by his own warped messianic pretensions.2 The fact that any self-conscious Christian can possibly admire such a man is a cause for sheer astonishment and sadness at how Christians today are incapable of discernment. John Brown showed such characteristic disregard for the authority of the Bible that he said with regards to abolishing slavery, “If any obstacle stands in your way, you may properly break all the Decalogue in order to get rid of it.”3

While there is no question that abolitionism was dominated by theological liberalism, even many of the supposedly orthodox abolitionists possessed dubious theological credentials. Many from a conservative Protestant background were nevertheless mired in liberalism, revivalism, and other theologically heterodox ideas. Many abolitionists came from long lines of prominent preachers, and their rejection of traditional Christian orthodoxy left a void in their lives that they filled with the pursuit of equality in the name of their Unitarian God. The abolition of slavery simply happened to be first in a long list of reforms on their agenda. The abolitionists included amongst their ranks many of the most famous preachers in the mid-nineteenth century, such as Lyman Beecher (the father of pulp novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe), Charles Finney, Theodore Weld, and Albert Barnes. Many of them ultimately found themselves facing ecclesiastical charges of heresy for their teachings not directly related to the slavery issue, which clearly establishes a connection between abolitionist exegesis and overt heresy.

Albert Barnes’s debate with southern Presbyterian Frederick Ross typifies the nature of abolitionist exegesis. According to Roger Schultz, in his article “The Politics of Righteousness,” he writes, “Barnes essentially said he didn’t care what the Bible said, since slavery violated the ‘spirit of love’ found in the New Testament. His final salvo against slavery was that ‘the instinctive feeling in every man’s bosom . . . is a condemnation of it.’ Given his emphasis on the ethical ultimacy of instinctive human feelings, it comes as no surprise that Barnes was deposed from the ministry in 1835 for Pelagianism.”

Frederick Ross, on the other hand, “insisted that it was dangerous to jettison scripture for speculative systems of ethics, noting that abolition rhetoric employed strained hermeneutics and was hostile to Biblical ethics.” Schultz concludes, “My impression is that Barnes, like most abolitionists, usually employed strong emotive and visceral arguments, while Ross was far more careful in dealing with Biblical texts.”

Schultz remarks of abolitionist Theodore Weld:

An excellent example of the theological confusion and rootlessness among evangelicals is Theodore Weld. Though reared in a strict Calvinistic manse, he was a protégé of Charles Finney and studied at Lane Seminary (at which Lyman Beecher was president), where he was part a group that styled itself the “Illuminati.” Weld’s early reform passions were for education and abolitionism. He became a women’s rights advocate after his marriage to Angelina Grimke, a Quaker feminist. (The Welds helped promote reforms like “bloomers”—progressive women’s attire in the 19th century). His American Slavery sold 100,000 copies in its first year and, in becoming an anti-slavery classic, made Weld the nation’s leading abolitionist spokesman. His wife, however, pursued a different track, latching onto the millennialism of William Miller, who predicted Christ’s imminent return in 1843. The Welds eventually drifted into spiritism, Swedenborgianism, and Transcendentalism. After struggling with a son’s insanity and suicide, and trying his hand at organic vegetable farming and teaching at a Utopian commune, Weld finally became a Unitarian. His life personifies Ephesians 4:14.

One final glimpse at abolitionist duplicity will suffice to show the dubious nature of this supposedly moral crusade. Henry Ward Beecher was the son of the aforementioned Lyman Beecher. Regarding Henry Ward Beecher, Schultz writes:

The most famous child was Henry Ward Beecher, the silver-tongued preacher at the nation’s largest and most prestigious church. He was active in abolitionist causes—guns shipped to Kansas during the anti-slavery chaos were dubbed “Beecher’s Bibles.” He was the leading ecclesiastical popularizer of evolution. But he received the most national attention in an 1875 adultery trial for the seduction of a friend’s (and church elder’s) wife. . . . In addition to fat salaries from the church and lecture circuit, Beecher collected fees for endorsements (including an endorsement for soap!). The rank story of his adultery trials are outlined in Robert Shaplin, Free Love and Heavenly Sinners (N.Y.: Knopf, 1954). The trial is very unusual, for at the same time that Beecher was allegedly having an affair with Mrs. Tilton, her husband was cozy with Victoria Woodhull, the notorious free-love advocate and the first publisher of Marx in the United States. The cases were dismissed (in ecclesiastical and civil courts), in part because Mrs. Tilton’s testimony was confused. She confessed to adultery, recanted her testimony, and confessed again; she later went insane. Boys in Brooklyn had little doubt about the charges. One of their favorite ditties was: “Beecher, Beecher is my name, Beecher til I die! I never kissed Mrs. Tilton, I never told a lie!”4

These brief biographical sketches should be kept in mind when we are told that the abolition of slavery in America was a great victory for Christian morality! It should easily be apparent that abolitionists most certainly did not represent either traditional Christian morality or theology in the way that they approached social problems. This is not to say that this era was entirely lacking in wise Christian insight. Southern Presbyterian pastors like Robert Lewis Dabney, James Henley Thornwell, and Frederick Ross were on the forefront of defending orthodoxy on the questions of slavery, as well as the other moralistic crusades that plagued America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And lest we think that the issue of abolitionism was purely a regional concern, it should be noted that one of the most compelling defenders of the South was none other than the Massachusetts Rev. Nehemiah Adams.

Did the Apostolic Spirit of Charity Militate Against Slavery?

Nehemiah Adams was a compelling figure in the nineteenth century. He was a Congregationalist minister from Massachusetts in an age where this was practically synonymous with abolitionism. Rather than follow the spirit of the age, which was slipping towards Unitarianism, Adams was a vocal proponent of orthodoxy. Adams applied this same orthodoxy to the burning question of slavery. Unlike most of his contemporaries in the abolitionist camp, Adams did something particularly radical: he actually traveled to the South to witness her “peculiar institution” firsthand. Upon returning home, he wrote a balanced and accurate account of what he had seen, and defended the South by demonstrating that the South was not practicing anything contrary to the Bible.

Adams points out that humans would generally be inclined to taking an egalitarian and abolitionist position:

Men with their benevolence and zeal, if left to themselves, would, some of them, have gone to extremes on that subject; for ‘ultraism,’ as we call it, is the natural tendency of good men, not fully instructed, in their early zeal. The disposition to put away a heathen husband or wife, abstaining from marriage and from meats, Timothy’s omission to take wine in sickness, show this, and make it remarkable that slavery was dealt with as it was by the Apostles.5

This natural tendency can be contrasted with the wise moderation of the Apostles. Adams correctly states that

The wise manner in which the Apostles deal with slavery is one incidental proof of their inspiration. The hand of the same God who framed the Mosaic code is evidently still at work in directing his servants, the Apostles, how to deal with slavery. . . . Only they who had the Spirit of God in them could have spoken so wisely, so temperately, with regard to an evil which met them every where with its bad influences and grievous sorrows.

While honest Christians are compelled to acknowledge the Apostles’ moderation in the way that they handle the issue of slavery, many still seek to extricate themselves from the conclusion that the Apostles thought that slavery was anything other than entirely immoral, if not the very worst of evils. Many suggest that the Apostles really were indeed opposed to slavery, but did not want to get sidetracked from preaching the Gospel. Adams alleges that in his day, the maxim regarding the Apostles’ view of slavery was that “they girdled slavery, and left it to die.” This is to charge the Apostles with cowardice, if it is true that they considered slavery to be intrinsically evil. The true preaching of the Gospel never interferes with denouncing evil! On the contrary, the two always necessarily go hand in hand. Thus it is entirely without foundation to suggest that the Apostles were ever merely passive in their opposition to any evil. Adams responds in his nineteenth century eloquence:

[T]his surely is not in accordance with the apostolic spirit. There is no public wickedness which they merely girdled and left to die. Paul did not quietly pass his axe round the public sins of his day. His divine Master did not so deal with adultery and divorces. James did not girdle wars and fightings, governmental measures. Let Jude be questioned on this point, with that thunderbolt of an Epistle in his hand. Even the beloved disciple disdained this gentle method of dealing with public sins when he prophesied against all the governments of the earth at once.But slavery, declared by some to be the greatest sin against God’s image in man, most fruitful, it is said, of evils, is not assaulted, but the sins and abuses under it are reproved, the duties pertaining to the relation of master and slave are prescribed, a slave is sent back to servitude with an inspired epistle in his hand, and slavery itself is nowhere assailed. On the contrary, masters are instructed and exhorted with regard to their duties as slaveholders. Suppose the instructions which are addressed to slaveholders to be addressed to those sinners with whom slaveholders are promiscuously classed by many, for example: “Thieves, render to those from whom you may continue to steal, that which is just and equal.” “And, ye murderers, do the same things unto your victims, forbearing threatenings.” “Let as many as are cheated count their extortioners worthy of all honor.” If to be a slave owner is in itself parallel with stealing and other crimes, miserable subterfuge to say that Paul did not denounce it because it was connected with the institutions of society; that he “girdled it, and left it to die.” Happy they whose principles with regard to slavery enable them to have a higher opinion of Paul than thus to make him a timeserver and a slave to expediency.

Obviously, the Apostles confronted evil forthrightly. The Apostles never tiptoed around a subject because it was sensitive — especially if the practice in question was really as evil as the abolitionists suggested. Instead, we can easily find clear and unambiguous denunciations of actual evil throughout the epistles. Since the Apostles believed that sin was a transgression of God’s Law (1 John 3:4), we should expect them to have forbidden Christians from engaging in the practice of slavery altogether if they actually believed that slavery ran counter to the Law. The abolitionists who argued that the Apostles “girdled” slavery and left it to die fancy that they were actually morally superior and more courageous than the Apostles themselves! Quite a proposition, when you consider the heterodox ideas that the abolitionists held dear.

This same logic is often used today who carry the abolitionist mentality to its logical conclusion. Feminists read passages that enjoin Christian women to submission to their husbands with utter disdain. They either reject these passages outright, or they assume that the Apostles really did believe in equality, but since women were treated as chattel in the first century, the Apostles did not believe that they were in a position to challenge established cultural norms on gender. This, of course, requires us to ignore the fact that the Apostle Paul and Peter demand submission from Christian women as a Christian duty, not because of cultural considerations (Num. 30; 1 Cor. 11:3, 14:34; Eph. 5:22-24; Col. 3:18; 1 Pet. 3:1-6). The underlying assumption is that we live in a more conscientious age than the Apostles lived. Therefore, we should be more proactive in confronting evils that they seemingly ignored.

This approach to the scriptures in entirely faithless and denigrates God’s Word. The Apostles confronted and opposed evil wherever they found it, and most of them gave their lives in the service of truth. The courageous attitude of the Apostles can easily be contrasted with the path taken by feminists and abolitionists who have allowed themselves to be carried away by the spirit of the age.

Conclusion

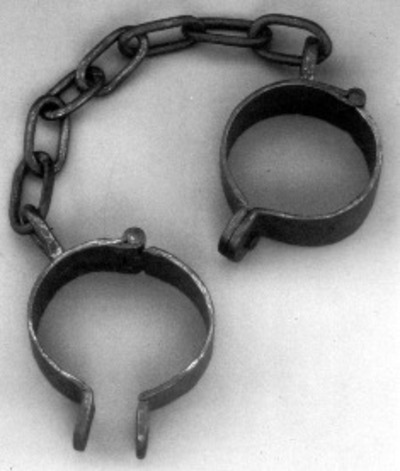

Even though legalized slavery ended throughout the Western world in the nineteenth century, the issue is still an important one to address today. What a person in my position is often asked is if I want to reinstitute slavery in America or elsewhere in the Western world. Many people will conjure up images of the whites exploiting and terrorizing non-whites, such that any defense of slavery, even in the abstract, is a defense of white oppression. Let me assure you that this is not the case. I have no desire to reinstitute slavery of whites or non-whites. Most whites intended slavery to be a temporary situation in which non-whites, most of whom were black Africans, would serve time as laborers and return home to Africa armed with Western manners, the Christian faith, and an elevated standard of civil society. There were various reasons why this did not happen, not the least of which was white complacency. While I will deal with some popular misconceptions of slavery next time, suffice it to say that I think that short-term participation by Western nations in the slave trade was a mistake that has had grave repercussions on the health of Western societies.

The primary reason that the issue of slavery is still relevant a century and a half after its abolition throughout the Western world is that the liberal methodology used by the abolitionists in the nineteenth century is used today by professed Christians who seek to make the Bible conform to their own preconceived notions about the way that society ought to be ordered. The abolitionists in the nineteenth century believed that slavery or servitude of any kind was wrong because it contradicted their egalitarian presuppositions. The master/slave relationship is predicated upon social inequality, not necessarily social injustice, as the writings of the Apostles make clear. The nineteenth-century abolitionists had surrendered their belief in Christian orthodoxy and erected an alternative construct for ethics and morality in place of orthodoxy. In place of Christian fellowship, which reconciles people of different social classes, genders, and nations, the abolitionists demanded that these distinctions be leveled in the name of equality.

The feminists and suffragettes immediately followed suit by applying this egalitarianism to gender issues. The abolitionists successfully overturned the natural order with regard to social classes, and the feminists were similarly successful in overturning the natural order with regard to gender. In recent decades, we have witnessed the so-called civil rights activists laboring to overturn God’s created order for national identity. For those who read the Bible through the lens of egalitarianism, the precepts and exhortations of the Apostles cannot be allowed to get in the way of their social engineering.

To be clear, no one is suggesting that oppression or unjust hatred can ever be justified. The effect of the Gospel is to reconcile people of different cultural, social, ethnic, and racial backgrounds. The Gospel does not eradicate these differences. Social inequality still remains after conversion, but masters and slaves are commended to each other in the love of Christian brotherhood. Christ makes it clear that He did not come to establish equality (Luke 12:13-14), and so we should not read equality into passages that speak of reconciliation. Inequality is embedded in our nature, and this reflects God’s purpose and design.

The purpose of the Gospel is not to change this, but to sanctify these differences and distinctions for the glory of God. Those who replace the ethics of the Apostles for the ethics and morality of unequivocal equality are bound to ultimately reject the authority of the Bible itself. It is no coincidence that the North was being overtaken by Unitarianism and agnosticism at the very time when they had focused their energies on ending what they deemed to be an intrinsically evil institution. This has only progressed to our current state of affairs, in which all distinctions and inequalities are considered evil. Sadly, the time has come when virtually all Christians believe that any crusade to end any form of inequality is thoroughly biblical and Christian. The Christian worldview — that God has created humanity as unequal members in society who can and should work together for the common good — has been replaced by a secular imitation. Thus we can easily see that the nineteenth-century debate over slavery was not simply about slavery, but about how one views inequality as something that is God-ordained and natural or necessarily evil. In this sense, the debate over abolitionism is as relevant as ever.

Footnotes

- Quote taken from Confederado, Southern Messenger, “Thornwell’s Prophetic Analysis.” February 20, 2006. http://southernmessenger.blogspot.com/2006/02/thornwells-prophetic-analysis.html ↩

- For a thorough and comprehensive treatment of John Brown’s homicidal crusade against slavery, see Otto Scott’s The Secret Six: John Brown and the Abolitionist Movement (New York: Times Books, 1979). Scott offers a definitive overview from a Christian perspective. http://www.amazon.com/The-Secret-Six-Abolitionist-Movement/dp/0963838105 ↩

- Otto Scott, The Secret Six: John Brown and the Abolitionist Movement (New York: Times Books, 1979), pp. 295f. ↩

- The above quotes are from The Politics of Righteousness: Christian Political Movements in the Early 19th Century. Roger Schultz. Contra Mundum. No. 4. Summer 1992. http://www.contramundum.org/cm/features/04_politics.pdf ↩

- Nehemiah Adams quotes are from Religion and the Demise of Slavery taken from A Southside View of Slavery. Nehemiah Adams. Boston: T.R. Marvin and B.B. Mussey and Company, 1854. http://www.southernslavery.com/articles/religion_demise_slavery.htm ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|