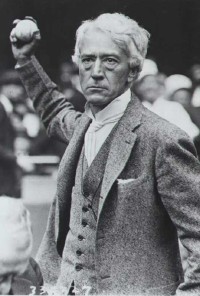

As we approach spring training for the upcoming season of Major League Baseball, we have a fascinating opportunity to give pause and to consider the legacy of baseball’s most controversial commissioner. Kenesaw Mountain Landis is famous to baseball fanatics as the first commissioner of Major League Baseball. He’s also infamous for his strong segregationist stance on maintaining separate white and Negro leagues. Landis’s decisions had a long and profound impact on the game of baseball, and it is interesting to speculate how baseball and American professional athletics would be different had Landis’s policies ultimately carried the day.

Landis was born in Ohio in 1866 and was named after the Civil War Battle of Kennesaw Mountain where his father, a Union private, was wounded. Landis dropped out of high school to work as a law clerk, eventually attended the University of Cincinnati, and graduated with a law degree from what is now Northwestern University Law School in 1891. Landis opened a law practice in Chicago, and in 1905 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Landis as a federal district judge for the Northern Illinois District. Landis’s association with professional baseball began in 1914 during an anti-trust injunction filed by the Federal League against Major League Baseball. This particularly piqued Landis’s interest in baseball, and he frequently attended Cubs and White Sox games in Chicago. In 1919, Major League Baseball experienced the infamous “Black Sox” scandal in which several players on the American League champion Chicago White Sox consorted with gamblers to “throw” the World Series so that the underdog Cincinnati Reds would win the Series and the certain gamblers would turn a large profit. The players were acquitted in court in the aftermath of the World Series and were allowed to return the following year. Pro baseball suffered immensely in the aftermath. Fans openly doubted the credibility of baseball contests, and owners were anxious to take the necessary measures to restore that credibility. In November of 1920, Landis was chosen by major league owners to become the first major league Commissioner. The owners agreed to give Landis almost total control over the internal affairs of baseball. It was the hope of many of the owners that Landis would help to clean up the game and then play a less active role in the management of the sport. Instead, Landis was anything but a figurehead, and his decisions shaped the game of baseball for the next two decades. By some he was known affectionately as the “Dictator” or “Tyrant.” Landis would serve in the post of baseball commissioner from 1920 until his death in 1944.1

Landis’s legacy in professional baseball is threefold. The first was Landis’s tough stance against players associated with gambling. Landis was responsible for banning eight White Sox players for life after the infamous “Black Sox” scandal, and he also banned many other players for throwing games or consorting with gamblers. The most famous player banned by Landis was “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. The second legacy of Landis was his attempt to curtail the increasing influence of major league teams over the minor leagues. Major league teams began buying the contracts of minor league players and eventually whole teams, beginning with the St. Louis Cardinals under the influence of Branch Rickey. Landis believed that minor league teams had the right to their own pennant races without the interference of major league teams calling up their star players. He was responsible for freeing many of the players who were under contract to major league ball clubs. His third and final legacy was the continued segregation of professional baseball into white and Negro leagues.

Landis is unique in comparison with most executives in professional sports today. It was Landis’s desire to maintain the integrity of the athletes who were allowed to compete. Landis was aware that athletes serve as role models and that they needed to have a sterling reputation. It could certainly be argued that Landis was too fast and loose in his willingness to ban players. There is certainly some doubt regarding whether every player banned for gambling was truly guilty. The most famous example of this question is Shoeless Joe Jackson. Shoeless Joe was a member of the Chicago White Sox during the infamous Black Sox scandal. He was implicated by teammates for his involvement in the scandal but steadfastly maintained his innocence. He was banned along with his teammates and is not in the Hall of Fame despite his career .356 batting average (3rd all time)! There are certainly circumstances in which Landis interpreted his powers too liberally, and he did have long feuds with several of the owners and long time American League President Ban Johnson.

It’s easy to dismiss Landis as nothing more than a tyrant obsessed with his own power and his perception of his own importance, but when we assess Landis and his position on the integrity of athletes, it is also easy to be sympathetic. Today’s athletes are disreputable. It is common to hear of many star ball players of all sports who are involved in shootings, drugs, drinking while driving, and abuse of their wives or girlfriends. (Oddly enough, hockey doesn’t seem to have the same problems. It must be because the players play with a puck instead of a ball!) Sports executives could certainly take a page out of Landis’s book in order to restore order and integrity to American sports.

Landis also lost his battle against the progressive incorporation of minor league players and teams into the major leagues. He was only able to score temporary victories in the battle to keep minor league teams independent. Eventually Branch Rickey, who had been hired by the St. Louis Cardinals as their general manager, would win out, and today every major league club controls their minor league affiliates. Personally, I used to be more favorably inclined toward Branch Rickey because I’ve been a lifelong Cardinals fan, and I considered Rickey to be an innovator. Over time I’ve come to respect the arguments that Landis made against incorporation. Landis argued that it was wrong for major league clubs to micromanage the affairs of other baseball teams. Incorporation would ruin minor league pennant races and unnecessarily rob their teams of talent. Sadly, Landis’s predictions came true. The incorporation of minor league teams by the majors started a process in which the game of baseball became increasingly more managed by purely commercial interests. There used to be a vast array of minor league teams loosely networked through many towns and cities, and were often organized in rural farm areas by local farm boys from neighboring communities. This is how the minor leagues came to be known as the farm system. These teams were associated with leagues of varying competition that were independently owned, operated, and managed. Most of these teams are no longer in existence because it became too expensive for major league teams to operate them, and the clubs could no longer compete with minor league teams affiliated with the majors. The size of the minor leagues greatly shrunk, and the eclipse of baseball as America’s pastime had begun. The farm system remains in name only as what was once the great system that grew baseball from the bottom up in America’s once fertile cornfields, and has been thoroughly dismantled by major league interests.

Landis’s third and final legacy was for the segregation of Major League Baseball into the white American and National Leagues and the black American Negro League and National Negro League. This is definitely Landis’s most controversial legacy today. Interestingly enough, this controversy also involved Branch Rickey, who began working for the Dodgers in the 1940s. Baseball was finally integrated after the death of Landis in 1944 and the ascension of A.B. “Happy” Chandler to the position as baseball’s new commissioner. Today, Major League Baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson, who became the first black player allowed to play for a white major league team in 1947. By 1949, the Negro leagues would be disbanded. One can’t help but wonder if the game of baseball has been improved through racial integration. Up until the Negro leagues were disbanded in the late 1940s, many inner city black boys routinely attended Negro league games. Desegregation in baseball had the same effects as desegregation generally. Back when there were segregated schools, businesses, and recreational facilities, blacks banded together and were able to create successful schools, businesses, and yes, baseball leagues. Columnist Elizabeth Wright reminds us that blacks created “institutions such as restaurants, stores, motels and movie theaters. There were banks, insurance companies, newspaper publishers. It is assumed that all blacks were helpless victims, financially crippled drudges, with no resources to pool among themselves. In fact, most of black entrepreneurial success originated in the South, the poorest region and the one of greatest need.”2 It is a little ironic that integration generally was pursued in order to further the interests of blacks, but ultimately ended up leading to demise of distinctly black institutions. The Negro leagues are a perfect example: within two years of integration the Negro leagues were defunct, and black participation in baseball has declined steadily since this time. It is not as though separate leagues were rooted in the idea that the two races could never interact. Since the inception of the game of baseball, blacks and whites had been playing together in exhibition games, and Landis never seemed to try to curtail this practice. Landis only tried to maintain the common wisdom of the time, which was unanimously enforced by baseball owners, that separate leagues were in the best interests of everyone. Given the history of integration in general and in baseball in particular, I see no reason to think that Landis was wrong.

As I reflect back on the history of game I’ve come to love so much as a spectator, I cannot help but regret that more managers and owners did not seek to maintain Landis’s legacy. The game of baseball has become very heavily commercialized, and baseball policies have gone further awry after Landis’s death. The designated hitter and free agency have largely changed the game of baseball for the worse as well. Landis was certainly as flawed a character as any. But he was also a man that showed considerable foresight and sound judgment in the policies that he pursued as Major League Baseball Commissioner. The passing of time has only served to vindicate his decisions.

For Further Reading

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Kenesaw Landis. http://baseballhall.org/hof/landis-kenesaw

Baseball Almanac. Kenesaw Mountain Landis biography. http://www.baseball-almanac.com/articles/kenesaw_landis_biography.shtml

Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Kenesaw Mountain Landis. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/329376/Kenesaw-Mountain-Landis

Footnotes

- MLB.com, Biographies of Major League Baseball Commissioners: Kenesaw Mountain Landis. http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/mlb_history_people.jsp?story=com_bio_1 ↩

- Wright, Elizabeth. The Civil Rights Myth: Integration and the End of Black Self-Reliance. Alternative Right. http://www.alternativeright.com/main/the-magazine/the-myth-of-civil-rights/ ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|