One of my Google Reader feeds is the website Occidental Dissent, run by Hunter Wallace. A few months ago a post of his prompted me to purchase a copy of The Road to Disunion, Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant, by William W. Freehling. I found this book to be profoundly interesting, despite its obligatory (for any historian wanting respectability and publication) anti-white bias. In 2006 I finished up Shelby Foote’s masterful trilogy on the War, but I found myself much more attentive and interested in the politics of the era, both before and after the war, than the minutiae of battles which took up the bulk of its space. Freehling’s book was exactly my cup of tea: the REAL plot that mattered, the politics leading to the war, and the strategists and players involved. Since I support the formation of a white ethnostate on the North American continent (or at least, more realistically, a state with permanent white hegemony, sort of like an Israel for white American Christians, likely achieved similar to the Israelis by a combination of gerrymandering and limited suffrage for the residual minority population), and I believe some form of secession is a necessary precondition for such an outcome, there is much to learn from the fire-eaters, a group that went from being seen as a marginalized group of extremists to mainstream political power in a remarkably short period by exploiting political opportunities.

My next post on this book will discuss these strategies, many of which are counter intuitive to what we typically hear. The book reveals the relatively small role (in terms of the acute secession crisis) played by the conventional actors: John Brown, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, hot-headed South Carolinians; it then highlights the actual players who were the immediate causes of secession: William Yancey, Hinton Helper and (unintentionally) Jefferson Davis. But more on this in the next post.

What surprised me about this book is how it affected my own feelings toward the South and the Confederacy. While I have not fundamentally changed my moral views of slavery or the rights of secession or the War (once Lincoln began raising an army to invade, secession and war was the only honorable option), I find myself questioning the wisdom of it, especially when I consider some of the very sympathetic actors on the other side. This is quite the change for me, as I had just finished Otto Scott’s The Secret Six, which expertly dissected the origins of abolitionism from the fever swamp of New England Unitarianism, legalism and self-righteousness. If the story were simply that of the likes of a heretic like William Lloyd Garrison versus the Christian civilization of the South (and this was my mental model before this book), it is easy to side with the South. However, the abolitionists were not the only players involved. They were the extremists most directly responsible for turning the slavery crisis into a shooting war (with their continual insults on Southern honor which short-circuited any hope of a peaceful resolution to the slavery and black issue), certainly, and the blood of every American killed in the War is certainly on their hands to a large degree. But there were other, more moderate voices present at the time, men working for a white ethnostate, with whom I found myself in sympathy.

Three of these men were Missouri congressman Frank Blair, Hinton Helper and Cassius Clay of Kentucky, a cousin of Henry Clay. While both were more-or-less abolitionists, their arguments focused less on the morality of slavery (which to my mind is not fundamentally in dispute – see Dabney’s Defense of Virginia for the definitive rebuke of abolitionist theology) and more on its purported effects upon free white settlers. Blair wanted a white Missouri to better compete for the high quality German immigrants* coming during this time, who preferred, all other things equal, a free labor state to a slave state like Missouri. Similarly, Clay sought for Kentucky to be a white man’s state by a delayed emancipation on a date-certain (which in effect would not deprive slaveowners of their property, as they could simply sell slaves to the Deep South states before the emancipation and recoup their investment), and arguably his support (and then disavowal) of abolitionist John Fee was a move of triangulation to make himself seem more moderate.

Like Clay’s Kentucky, Missouri was only lightly enslaved, and Blair supported purging Missouri of its remnant of slavery to make it more attractive to highly productive free white settlers. Hinton Helper was a Southerner who published a book of propaganda against slavery, in terms of how it hurt the free white population and economic development of the South. His argument was that slavery enabled capital-rich planters to purchase the best land, leaving poor whites with the least desirable land. I am less convinced by Helper’s argument as this seems to be the same old story of envying the rich for their being better stewards of their resources. The Old South was full of poor whites who through thrift and industry enlarged their estates, and their neighbors, who were less thrifty and less industrious, gladly sold them their assets. It is hard to argue that landowners should not take the highest bid because to do so would be “unfair” to the poor white man who had not accumulated any capital.

However, I am more sympathetic to the position of Blair and Clay, in wanting to make their states white ethnostates. It is arguable and defensible in my view that preserving the ethnic identity of a state is a legitimate goal of government, and to the extent this hindered individual liberty to own slaves it must be seen as a necessary evil. Certain activities (like importing blacks) have “externalities” associated with them, i.e. costs that are borne by neither the buyer or seller. Just as the state may legitimately prevent a refinery from dumping known toxics like benzene into a common body of water, it also has the right to prevent pollution of the body politic upon which the entire basis of law and society partially depends**.

On the other hand, I understand what motivated secessionists such as Yancey and Rhett. In reaction to abolitionist legalism, the South had committed itself to the notion that slavery was not just a necessary evil but rather a positive good. Theorists such as Virginia’s George Fitzhugh made the case for a natural aristocracy among men, that some form of slavery is inevitable, and better for it to be formal slavery with its concomitant duties and responsibilities (such as caring for aged slaves, provision of medical care, housing, etc) than an informal debt-and-wage-based slavery such as that practiced in the Northern states. That some men are born slaves seems incontrovertible; one only has to observe the mass of unemployable losers leaching off of our current government too see this reality. Fitzhugh even believed that some form of slavery was appropriate for people of all races, including whites, who were degraded by runaway capitalism to such an extent that they became dependent upon public charity. These men also believed that race slavery allowed more white men, especially of the better type, to pursue lives of leisure, freeing them up to more fully reach their potential, and leading to an overall higher level of civilization.

This attitude, a reaction against the abolitionists, was a substantial change from previous southern attitudes. As Robert L. Dabney is at pains to point out in his Defense of Virginia, it was the Crown of England, enriched and encouraged by New England slave traders, that forced African slavery upon Virginia. The early post-Revolution South was full of recolonization societies, and the Jeffersonian fatalism towards slavery’s ultimate demise (and the recolonization of blacks) was a mainstream opinion. Such a reasonable and Christian approach to solving the issue could not be long tolerated, so in due time the demons of Unitarianism, transcendentalism and abolitionism came to the fore to make any reasonable solution impractical. A great strength and weakness of Southern character is that of pride, sometimes sinful and sometimes not, but never amenable to being told what to do. The thought of these lapsed Calvinist Yankee hypocrites – these heretics who deny the Divinity of Christ – whose own ancestors were the lawbreaking man-stealers who created the slavery problem, telling the South that its entire way of life was an abomination – this was truly unbearable.

Probably the most offensive abolitionist rhetoric was their perverse fixation upon the idea of the Southern master as sexual predator; their continual beating of this drum, of turning the debate into a referendum of Southern sexual purity, anticipated the Freudian attacks experienced by conservatives of the 20th and 21st centuries and hardened the position of both sides. The line of “you’re so angry because you’re sexually repressed,” hurled at conservatives who complained of cultural Marxist destruction of their societies (the major breakthrough of cultural Marxism was the idea that race and sexuality, not income inequality, represented the weakest point upon which to break Christian civilization) is very comparable to the abolitionist charge of “you’re only defending slavery so you can keep your Negro harem.” That men wealthy enough to afford land and slaves (who cost anywhere from $20,000-$30,000 each in today’s dollars), if inclined to sexual sin, might have access to a more attractive option than illicit mating with a black servant (which would have been impossible to hide – we forget how little privacy is afforded to very wealthy people with full-time servants) never intruded upon this fixation of the abolitionists, which tells us more in my view about their own demons, who would soon move on to outright promotion of miscegenation, than anything about Southern sexual mores.

In fact, while Freehling is at pains to provide several anecdotal incidents of master-slave miscegenation to dignify the abolitionist charge (and imply that it stung Southern honor so much because it was true), we can actually estimate the degree of miscegenation with genetic testing. According to the most reliable sources, DNA analysis has revealed that African-Americans are about 17-18% white on average. While this may seem like a lot, remember that the “one drop” convention of American social life before about 1950 ensured that any white blood simply accumulated in the black gene pool. Under the most damning set of assumptions for Southern masters, let us pretend that miscegenation has been constant for all of American black history. If we take the year 1700 as the year for the average full-blooded African to arrive in America, and assume the average age of childbirth was 20, we calculate that there have been 15.55 generations of blacks in America. To calculate the average admixture per generation, we only have to raise the inverse proportion of white blood to the inverse power of the number of generations, so (1-0.175)^(1/15.55) = 0.9878 and subtract the result from 1, which leaves us an average admixture per generation of about 1.2%. Since we know most of this miscegenation has taken place since 1900, and on an even more accelerated basis since 1950, these Southern masters were some of the most chaste slave-owning patriarchs in history, which makes sense because of the genetic distance between Europeans and Africans, and the effects of that on mutual attraction between white men and black women (compare by contrast the numerous and frequent pairing with concubines and servants in the Old Testament when both masters and slaves were from genetically similar groups). Also note how liberal rhetoric changed: before the War, racist slavery was said to cause miscegenation, whereas 100 years after the War racism was held to prevent miscegenation, now promoted as a positive good.

To these false and malign insults to Southern honor, and in true Southern form, a reactionary blow-back responded that marginalized any hope of a peaceful and gradual end to slavery through recolonization. Those most reactionary Southerners’ Southerners, the South Carolinians, proceeded to develop an elaborate ideology defending slavery as an explicit blessing instead of a necessary evil. James Henry Thornwell, the great Presbyterian theologian, took the lead on the moral front. He made the obvious case that slavery is explicitly authorized in the Bible, though he did advocate reforms of the system, notably preventing the separation of slave families and protection against capricious cruelty from masters. What is notable is the seriousness with which he advocated these reforms, even in the midst of reactionary feelings towards the abolitionists.

Dabney concurred with Thornwell’s belief that slave families should be protected from separation and their marriages recognized under law. However, Dabney was careful to point out that an institution’s deviations from an ideal form do not automatically undermine an entire institution. Note that slave family separations, while occasionally the intention of callous and cruel masters, were mostly initiated by creditors possessing a bankrupted estate, who legally had to auction every slave to the highest bidder. Like all farmers for all history, the Southern planters got excited by high crop prices, which resulted in overinvestment funded by debt, then oversupply, then a collapse in prices followed by a liquidation of assets by creditors of the most overextended estates. Dabney and Thornwell supported slightly abrogating the rights of slaveowners and their creditors such that slave families could not be separated. In Dabney’s sermon upon the death of Stonewall Jackson, he repeatedly refers to Jackson’s death as a consequence of the sin of the Southern people; one wonders what exactly he had in mind. It is dangerous business to not respect God’s law, because you never really know how much any one offense will spur Him to action (and offend him it does, as He is holy), as often God will use Canaanites like the Unitarian Yankees to discipline His people when they stray off course. Freehling reports that, at the moment of secession, Thornwell was visiting Europe, and when the news was delivered he immediately thought that the drive to secession was the road to ruin for South Carolina, and that the foolishness thereof was a punishment of God for the South’s refusal to reform slavery to both keep families together and allow the Gospel to be preached to slaves (while most masters allowed this, Thornwell thought that no master should have the legal authority to require a slave to work on the Sabbath, nor prevent a slave from attending church services). Thornwell immediately resolved to return home and advocate for gradual emancipation such that South Carolina, in his view, might escape war and God’s wrath, but he demurred upon observing the impossible political situation on his return. The moderate response of this South Carolian theologian, so important in the 1850’s for defending the morality of slavery, at the moment of secession contrasted greatly with the fire-eaters who worked on the political front.

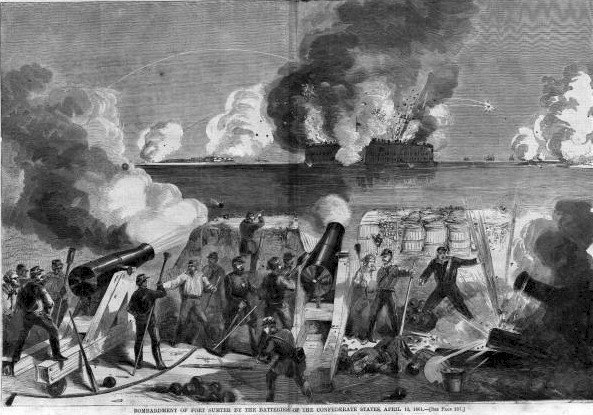

Robert Barnwell Rhett provided early political agitation for secession through his newspaper, The Charleston Mercury. In the classic biography of Jefferson Davis by Eckenrode, Rhett is portrayed as the visionary who saw the South and its institutions doomed if it did not seek political independence, which was seriously considered in 1850 at the Nashville Convention; in 1850, before the massive waves of immigration providing fresh conscripts, accelerating industrialization of Northern manufacturing and modernization of the US Army under, ironically, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, it is likely the South could have easily have defeated any Yankee invasion. However, Davis was a Unionist at the time who derailed the plans of Rhetts’ radicals.

A young lieutenant of the early fire-eaters, a South Carolinian who moved to Alabama, was William L. Yancey. I will explore Yancey’s genius as described by Freehling in my next post, but suffice to say that the man was ideally positioned because he was a hybrid South Carolinian, radical in his policies but practical in his politics. South Carolina at the time was the last aristocratic republic of the 18th century, frozen in time 100 years later. To serve in the South Carolina legislature, a gentleman had to own property worth 10 slaves plus 500 acres. To be a state senator, the candidate was required to own 1000 acres, and to be governor, 2500 acres. South Carolina was the only state in 1860 where the legislature selected the governor, and also the only state where the legislature alone picked presidential electors, without input from voters. The South Carolina ethos was to put superior men in positions of authority and let them make decisions for their lessors. This was at least due to a greater English influence in South Carolina, where greater wealth (in the pre-Cotton era at least) enabled more of their gentlemen to receive English educations, and also the fact that the state itself was a colony of Barbados, whose culture was more of the British Imperial tradition than the colonial tradition of the United States.

I must confess that I simply love the state of South Carolina, its culture, its literature, everything about it. It’s everything that’s beautiful about New Orleans and Louisiana, minus the decadent Latin influence, an Englishman’s lowcountry culture. However, as we look into the self-image of the South Carolina elite, we start to see the essential problems. The South Carolina elites were self-consciously trying to reproduce the aristocratic system of England, the picture-perfect pastoral contentment that instantly lowers the blood pressure when I view a Jane Austen movie; biology, unfortunately, gets in the way, as there are real biological limits when the aristocratic society is comprised of blacks instead of white peasants. The coastal counties of South Carolina were often 80-90% black, which takes me to my final point. These Southern gentlemen, then, can be seen as noble but quixotic reactionaries who were the last vestiges of feudalism against the dehumanizing wave of materialistic modernism. Even if we grant that feudalism is a better mode of society, its advantages mostly lay in a better quality of community and cultivation, and so could not overcome the biological limits of Africans, nor the brute force of Yankee war manufacturing.

The ultimate test case for whether the Confederacy was a viable society is provided by South Africa. The reality of why South Africa failed in my opinion is as follows:

1. Blacks are definitively materially better off under white rule.

2. As a consequence of #1, blacks will have higher fecundity than whites. Less intelligent, less responsible individuals will always have more children, lacking the self-control to voluntarily limit births. White medical care guaranteed that more of these children would survive to adulthood than white children.

3. The reliance on cheap labor distorts the economy and begets more and more demand for additional cheap labor, a race to the bottom demographically.

4. Eventually, as in South Africa, the less intelligent racial groups overwhelm demographically. Once South Africa reached a tipping point it was impossible even for the very skilled Boers to keep the criminals in line. The extremely high ratio, in the contemporary world, of the destructive potential of cheap terrorism versus the extremely high cost of preventing it were contributory factors. See John Robb’s work for more on this. Essentially, modern societies are complex and fragile, with severely expensive and vulnerable choke points (like power distribution stations, water sanitation facilities, etc). As the Confederacy inevitably modernized with the rest of the Western world, a scary but containable Nat Turner Rebellion, especially supported by outside agitators, could easily become a successful terrorist organization like the ANC. It is entirely plausible that the slave codes enacted after Nat Turner were perfectly necessary, as the same literacy required to read the Bible could be used to read abolitionist propaganda. This serves as an additional demonstration that multicultural societies are inherently unstable and unjust (to both groups), as they are contrary to God’s Providence. Whites could not be reasonably be asked to consent to having their slaves read the Satanic propaganda of the abolitionists, but the injustice of preventing slaves from reading the Bible struck at the very heart of the North European sense of individual religious liberty, hard-won through the Reformation. The only solution to both wrongs was racial separation.

5. The ultimate outcome of the War were the “Jim Crow” laws of the Redemption period, where Southern whites finally abandoned their paternalistic delusions towards blacks and went about setting up an explicitly white government. Over the next 100 years, the South would become whiter demographically as blacks moved to Northern urban areas (the Confederacy at its birth was 59% white; South Carolina, of course always the most extreme example of nearly anything, was at best 42% white on the eve of the War, and according to the 2010 census is now 66.2% white). Now the South is again the hotbed of secession-type talk through the Tea Parties, only this time with a much whiter self-identity. Perhaps we can start to see God’s Providence and mercy towards His people in the South at work, which was so hard to understand in the immediate aftermath of the War. The South is a much nicer place to live today, and a much more viable future white hegemonic nation, than South Africa. The sacrifices of our ancestors, however, were not in vain, as the post-war Reconstruction period served as a crucible to unify the whites of the South. Perhaps we can dream of a day when an independent American Heartland nation will welcome the Boers as refugees, completing the circle of Providence for both groups of similar faithfully Christian whites faced with such historical Hobson’s choices. I am reminded of Robert E. Lee’s immortal words in reflecting on the War:

“My experience of men has neither disposed me to think worse of them, or indisposed me to serve them; nor in spite of failures, which I lament, of errors which I now see and acknowledge; or of the present aspect of affairs; do I despair of the future. The truth is this: The march of Providence is so slow, and our desires so impatient; the work of progress is so immense and our means of aiding it so feeble; the life of humanity is so long, that of the individual so brief, that we often see only the ebb of the advancing wave and are thus discouraged. It is history that teaches us to hope.”

These two visions, that of the free white republic of Blair and Clay on the one hand, and that of the aristocratic racial feudalism of Thornwell and Fitzhugh, are the two competing visions of how whites should utilize their gifts in relation to wider mankind. The free white republic is the ideology of European nationalism and self-sufficiency. Racial feudalism is the philosophy of white supremacism and imperialism. I used to not be so quick to dismiss the latter. It is a tempting vision, indeed, to see how much better off black slaves in America were compared to their relations in Africa. When we observe Africa, a continent of boundless resources, full of people created in the image of God who live in such degradation relative to Europeans, it is attractive to imagine that white leadership, such as that provided by the colonizers, is the God-ordained order of things, enriching the white and black alike through the white man’s superior skills of dominion over creation. Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” shows why this is fallacy:

Take up the White Man’s burden–

And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better,

The hate of those ye guard–

The cry of hosts ye humour

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light:–

“Why brought he us from bondage,

Our loved Egyptian night?”

It asks too much of men to allow aliens to lead them. Any group of people, and as Kinists we must respect this instinct, would rather be ruled by a butcher and incompetent from among their own than the most benevolent alien. Just as we rightly oppose the ruling of our societies by arguably superior East Asians or Ashkenazi Jews, Africans oppose any attempts at European leadership, for they too feel the call of the blood that they alone, according to God’s decree of nations, should determine their collective fate as a society.

Perhaps there is another way for the white man to provide much-needed leadership to Africa and other Third World nations without triggering rebellion; the Cold War approach was the soft colonialism of the puppet dictator, who ruled over his own people while allowing Western countries to develop his country with the skills his natives lacked. While this worked in many cases, it also gave us fundamentalist Iran and Saddam Hussein; even puppets resent their strings it turns out. Nevertheless, these are mere speculations. The situation of the European race is currently too precarious to worry anymore about how to help the Third World. In fact, no help at all may be ultimately necessary; the free market, using white technology, is already doing a fabulous job of elevating the poor people of the world. Ethiopia, for example, has a 2008 life expectancy of 56, which is equivalent to the life expectancy of a United States citizen in 1920, at which time an Ethiopian could expect to live to 30 years, an improvement of 87% over the last 90 years. White people should consider this carefully: when Africans are now only 90 years behind the Western world (in terms of quality of life), is it really necessary to continue this destructive rescue fantasy where we ruin our own homelands to “save” (and morally corrupt through welfare) a tiny sliver of the Third World?

The task at hand is the self-preservation of European peoples with ethnostates in their historic homelands: Europe, Russia, the Americas, Australia and New Zealand, and at least parts of South Africa if possible. We will gladly grant to every other people their place under the sun according to God’s ordained order if our own sovereignty is respected.

Notes:

* It is a misconception that all German immigrants were anti-slavery. In general, the German colonization societies tended to encourage more conservative (and slavery-tolerant) Germans to move to slave states like Texas, whereas “freethinker” liberal Germans were encourage to settle in free states. Chronicles Magazine published an article a few years back definitively defending German Texans of the charge of disloyalty during the War.

**I believe genetics AND culture/religion both contribute to determine the nature of a society, and changing either will necessarily change the society; the religion reductionists have a blind spot in this area – Haiti or Uganda is clearly more Christian than Denmark, but no matter how Christian Haiti becomes, it is unlikely because of genetic constraints to ever approach the standard of living and societal characteristics of Northern European groups. Of course, salvation is dependent upon true faith in Christ, not GDP, so it is entirely plausible that a Christian African society, while likely to be better off than non-Christian African societies, would contain more of God’s elect than an advanced but atheist European society. However, the non-religious characteristics of both societies are God-ordained and worthy of protection. Some religion reductionists believe Europe is coasting on its Christian heritage and will return to a much lower level of civilization once neo-paganism and atheism completely runs its course on social mores and values. Time will tell if this prediction is correct. The Chinese have never been Christian yet have maintained a relatively high level of civilization compared to Africa throughout their history, as did the Greeks and Romans.

| Tweet |

|

|

|