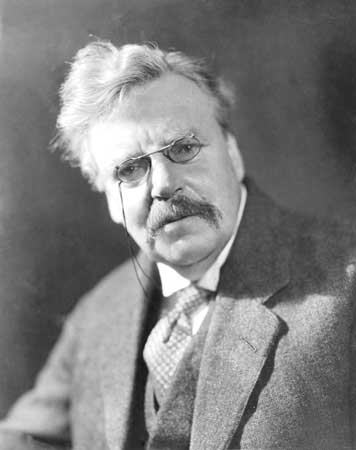

Several months back, I posted an excellent quote by G.K. Chesterton on democracy and tradition, and today I’ll be following that up with some excerpts and discussion of Chesterton on economics. To reiterate, G.K. Chesterton was a British writer and philosopher who lived from 1874 to 1936. He wrote many books defending and discussing the Christian faith, and despite my disagreement with his Catholicism, I have found many of his works and quotes to be brilliant and well worth the read. Chesterton was one of the founders of the economic theory of distributism, which offers very deserved critiques of both socialism and capitalism, and which advocates for a more pro-tradition and pro-human economic model. This is what this post will be specifically addressing today. I recently ran across the transcript of a talk given at the 2001 American Chesterton Society annual conference entitled “G.K. Chesterton and Dorothy Day on Economics: Neither Socialism nor Capitalism.” While I would certainly take issue both with the talk’s tirade against Calvinism as the root of all our modern economic ills, and with its insistence in rooting social organization in submission to the Papacy, I do think that there is a lot of value in it for the discerning reader, especially in the quotes from Chesterton.

So what is distributism?

The economic philosophy of both The Catholic Worker and Chesterton was distributism and at the heart of distributism is private property. The word distributism comes from the idea that a just social order can be achieved through a much more widespread distribution of property. Distributism means a society of owners. It means that property belongs to the many rather than the few.

Or, as Chesterton put it, “Too much capitalism does not mean too many capitalists, but too few capitalists.” In other words, the ownership of capital and the means of production should be controlled by many families, small businesses, and local cooperatives, rather than by a few large corporations. It is the distributists’ contention, with which I tend to agree, that the greater profitability due to the increased efficiency of centralization in huge corporations in the short run is more than offset by the long-term damage done to individuals and society. This damage consists of huge sections of the population being dependent wage-slaves, in addition to the supreme danger of concentrating the vast majority of a society’s wealth into the hands of a few corruptible men. Note that the redistribution of wealth is a very different philosophy from the distribution of property: the difference between giving a man a fish and teaching a man to fish, to use the cliche.

Dorothy described it this way: “The aim of distributism is family ownership of land, workshops, stores, transport, trades, professions, and so on. Family ownership in the means of production so widely distributed as to be the mark of the economic life of the community—this is the Distributist’s desire. It is also the world’s desire. (The Catholic Worker, June 1948)

Chesterton contended in What’s Wrong with the World that “property is merely the art of democracy.” For him, property meant, “every man should have something that he can shape in his own image, as he is shaped in the image of heaven. But because he is not God, but only a graven image of God, his self-expression must deal with limits; property with limits that are strict and even small.”

He illustrated the difference between the idea of Private Property of distributism and that of the Private Enterprise of capitalism: “A pickpocket is obviously a champion of private enterprise. But it would perhaps be an exaggeration to say that a pickpocket is a champion of private property. Capitalism and Commercialism . . . have at best tried to disguise the pickpocket with some of the virtues of the pirate. The point about Communism is that it only reforms the pickpocket by forbidding pockets.”

Chesterton said, “It is all very well to repeat distractedly, ‘What are we coming to, with all this Bolshevism?’ It is equally relevant to add, ‘What are we coming to, even without Bolshevism?’ The obvious answer is–Monopoly. It is certainly not private enterprise.”

Under the editorship of Dorothy Day, The Catholic Worker criticized an unbridled capitalism which put the majority of money and resources in the hands of a few big corporations and individuals. At the same time Dorothy noted, the people she called robber barons spoke against socialism and defended private property.

Chesterton pointed out the irony of this: “One would think, to hear people talk, that the Rothschilds and the Rockefellers were on the side of property. But obviously they are the enemies of property because they are enemies of their own limitations. They do not want their own land; but other people’s. . . . It is the negation of property that the Duke of Sutherland should have all the farms in one estate; just as it would be the negation of marriage if he had all our wives in one harem.”

Thus on the one hand, we have an affirmation of private property against socialism and a contention that capitalism is also an assault (although more subtle) on private property. And on the other hand, we have agreement with the socialist about the social injustice which capitalism creates and agreement with the capitalist that the destruction of private property is an extreme evil.

Both Chesterton and The Catholic Worker criticized monopoly capitalism, where a few wealthy capitalists owned the capital and the majority, the masses, worked each day in monotonous jobs. Chesterton and The Catholic Worker insisted that all people were created in the image and likeness of God, and should not be treated like cogs in a machine (or made to work twelve hours a day in back-breaking work as wage slaves), while large corporations and their directors became fabulously wealthy. However, Chesterton, Maurin and Day knew that Socialism was not a solution, and frequently criticized it as well.

Most modern right-wingers consider themselves capitalists, and thus I suspect that they may not be liking this article so far. They are rightly opposed to the evils of Marxism and communism and hold to private property and free enterprise, which is what they’ve been told capitalism embodies. However, what the average American considers to be capitalism and the way capitalism is actually practiced are two very different things. Chesterton’s attacks are aimed primarily at the latter and not the former.

To clarify for his [Chesterton’s] readers what he was criticizing, he first described the situation where a few people hold the wealth and all others struggle: “When I say ‘Capitalism,’ I commonly mean something that may be stated thus: ‘That economic condition in which there is a class of capitalists roughly recognizable and relatively small, in whose possession so much of the capital is concentrated as to necessitate a very large majority of the citizens serving those capitalists for a wage.'” He emphasized that others had something quite different in mind when they spoke of capitalism:

“The word . . . is used by other people to mean quite other things. Some people seem to mean merely private property. Others suppose that capitalism must mean anything involving the use of capital.

“If capitalism means private property, I am capitalist. If capitalism means capital, everybody is capitalist. But if capitalism means this particular condition of capital, only paid out to the mass in the form of wages, then it does mean something, even if it ought to mean something else.

“The truth is that what we call Capitalism ought to be called Proletarianism. The point of it is not that some people have capital, but that most people only have wages because they do not have capital.”

This is not to say that everyone must own their own business and that no one should work for wages—far from it. However, as far as it is practical and as far as each individual’s abilities allow, economic activities like production should be small and widespread, whether through small businesses, family affairs, or single-person enterprises. Further, this is not to say that there will be complete economic parity without the distinction between rich and poor—again, far from it. However, distributism would provide the basis for a much more equitable system, an alternative to having a tiny number of the super-rich and a vast amount of the very-poor. It would allow many more opportunities for upward mobility and more just economic rewards for work.

One of the major tenets of of distributism is widespread land ownership and encouraging local agriculture.

Dorothy quoted Joseph T. Nolan from Orate Fratres on the support of Popes in their encyclicals for the CW position: “Too long has idle talk made out of Distributism as something medieval and myopic, as if four modern popes were somehow talking nonsense when they said: the law should favor widespread ownership (Leo XIII); land is the most natural form of property (Leo XIII and Pius XII); wages should enable a man to purchase land (Leo XIII and Pius XI); the family is most perfect when rooted in its own holding (Pius XII); agriculture is the first and most important of all the arts and the tiller of the soil still represents the natural order of things willed by God (Pius XII). (Catholic Worker, July-Aug. 1948)

Despite the source, this does line up well with our own American experience, common sense, and biblical wisdom. The small freeholding farmer and tradesman, having the means to provide for himself apart from the government or corporation, has always been the bane of tyranny. Our own Colby has expounded upon the virtues of tilling the soil, even if only in a small backyard garden. There is something intangible, but very real and positive, in the ownership of land which should be encouraged (probably something to do with the ingrained command of Genesis 1:28-30). It would be prudent to point out that despite the (arguably legitimate) emphasis distributism places on agriculture, it is not necessary to be a farmer to be a distributist. The shop owner, tradesman, and small businessman in the town are just as necessary for the distributist economy as the tiller of the soil.

Some will argue that this all sounds well and good, but it is impossible or impractical. Chesterton answers them:

In The Outline of Sanity, making the case [for] distributism, Chesterton argued, “They say it is Utopian; and they are right. They say it is idealistic; and they are right. They say it is quixotic; and they are right. It deserves every name that will indicate how completely they have driven justice out of the world; every name that will measure how remote from them and their sort is the standard of honourable living; every name that will emphasize and repeat the fact that property and liberty are sundered from them and theirs, by an abyss between heaven and hell.

“Distributism may be a dream; three acres and a cow may be a joke; cows may be fabulous animals; liberty may be a name; private enterprise may be a wild goose chase on which the world can go no further. But as for the people who talk as if property and private enterprise were the principles now in operation—those people are so blind and deaf and dead to all the realities of their own daily existence, that they can be dismissed from the debate.”

This article is certainly not intended to be the final word on the subject, but I do hope that this has given you something to consider. Hopefully, it will aid in moving us away from our current economic model and towards a more Christian and man-centered (as opposed to profit-centered) system.

In closing,

“To say that I do not like the present state of wealth and poverty is merely to say that I am not the devil in human form. No one but Satan or Beelzebub could like the present state of wealth and poverty” (G.K. Chesterton, The Outline of Sanity, London, Methuen and Co., pp. 108, 151, 148).

| Tweet |

|

|

|