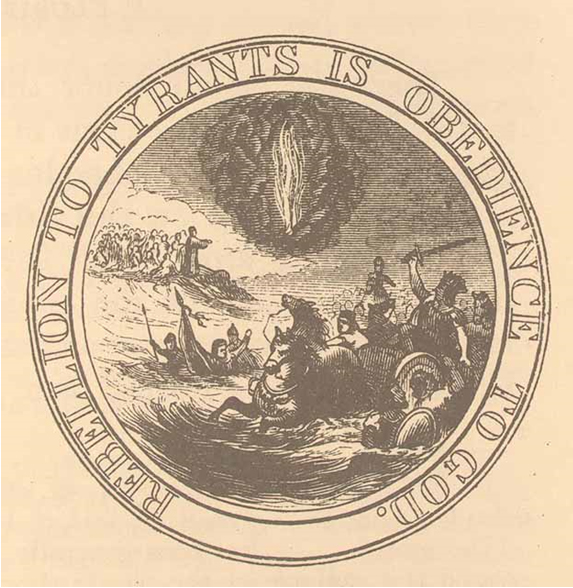

The original Seal of the United States of America as commissioned by the Founding Fathers in 1776: it depicts the drowning of Pharaoh’s army in the Red Sea. The motto along its perimeter suggests that war against the British crown was sanctioned by God and that America was a nation in covenant with God, like Israel of old.

In America religion is the road to knowledge, and the observance of the divine laws leads to civic freedom.

~ Alexis de Tocqueville1

I confess from the outset that the topic I undertake to examine here strikes me as awkward. Oh, we’re all well enough inured to indictments of the American Constitution from the Afrocentric, Muslim, and Lincolnian Left – that it is inexcusably flawed on account of being ‘Eurocentric,’ ‘patriarchal,’ and ‘too Christian,’ but vindications aplenty have been written contra that perspective and it is no longer the debate of the hour.

Besides, those who have denounced the Constitution in such terms cannot find a way around citing the provisions of the Bill of Rights in their defense. Ironically, Liberals cannot argue against the Constitution without simultaneously sheltering beneath its wings. That is, they cannot deny it without also affirming the thing itself and the concept of constitutionality back of it. Albeit, from the midst of that shelter, when they have argued the other direction – that the Framers were deists who established anti-Christian secularism – that perspective was easily enough dismissed by the flood of citations from the founding era, or, just as often, with a wave of the hand. Because modern secular Liberals arguing that the Founders – when they weren’t declaring days of thanksgiving, consecrating the business of Congress with Christian prayer, affirming America as a White ethno-state, or printing Bibles – were modern secular Liberals, like unto the denizens of 1969 UC Berkeley, was evident for nonsense.

But if all those Leftist arguments have been weighed, measured, and dismissed, a new permutation of this issue is rearing up from an unexpected source – the Right, and the Alt Right especially. Albeit the Rightists in question are co-opting whole cloth the arguments of the Liberals which preceded them, but objecting on opposite grounds: where early-twentieth-century Liberals reinterpreted the Constitution as a secular-deist or Masonic-Luciferian document meant to directly prevent Theonomy and White Christian hegemony, and affirmed it under those terms, desperate Conservatives are turning to denounce the Constitution on the basis of that Liberal interpretation. And even if those levelling the charge from the Right are in the minority, it is a growing and vocal minority necessitating redress.

If the Traditionalists who would otherwise put down those cavils have waned in number, conviction, and influence, those arguments have been addressed by just about every paleoconservative and patriot thinker throughout the twentieth century. They did such a good job of defending the Christian underpinnings of the Founders’ thought that even those historians who reject the Constitution as a Christian covenant have oft been compelled to admit that “the Founders identified themselves as Christians. Clearly, they did. In 1776, every European American . . . identified himself or herself as a Christian. Moreover, approximately 98 percent of the colonists were Protestants, with the remaining 1.9 percent being Roman Catholics.”

Gary North was the one to open this Pandora’s box on the Right via his book Political Polytheism: The Myth of Pluralism and later by a revision of the same under the title Conspiracy in Philadelphia. But even if he promulgated this ‘CONstitutional’ theory as his own, it had been a default orthodoxy of the Left first. More than that, he actually learned it at the feet of Leftist professors directly. More on that shortly.

Nonetheless, North has managed to pass the baton on this thesis to others. Leading the charge today, it seems, is Reverend Ted Weiland. I recognize many CI do not admit Weiland among their number, but his audience is all but entirely CI. Make of that what you will; identifying him as CI is convenient for our purposes in this discussion.

As the reader likely knows, Kinists and CI differ in respects of anthropology, and in some instances, soteriology. Granted, CI is rather difficult to address as a singular system on account of its inclination to encompass such a broad ecumenism, but CI folk have held fast as consistent advocates of Theonomy and the common law applications thereof in Christendom past. At least until recently. In fact, they used to host an indefatigable stable of constitutionalist authors. Case in point, this sudden anti-constitutionalist turn in those quarters would come as quite a surprise to the likes of CI Jack Mohr, who wrote exultantly of America’s founding as a “Christian constitutional republic.” As a Kinist I may disagree with Mr. Mohr about certain issues, but constitutionalism isn’t one of them. And I count him to have been a very solid thinker on other subjects, besides.

But Mr. Weiland has not only written much contrary to the Constitution; he maintains that persuading Christians to repudiate that document is a central focus of his ministry because, in his words, the Constitution is “the reason America is teetering on the precipice (or, actually, already falling into the chasm) of moral depravity and national destruction.” Or, as others have stated it, “The Constitution either caused the problems we have today, in which case it’s evil; or it allowed them, in which case it’s useless.”

This view is also gaining ground with Southern nationalists such as Al Benson, Jr., as there has been a good deal of cross-pollination between CI and Southern nationalism and between Southern nationalism and the Austrian School of economics – which is the origination point of this view on the Right via Gary North. For the purposes of this discussion North must be categorized as an Austrian School libertarian rather than a Reconstructionist/Theonomist, because his stance on this issue is antithetical to that not only of R. J. Rushdoony, but of all his theonomic predecessors.

Inasmuch as the Southrons have righteous grievance against the Union and all Americans against the federal government, the compulsion to ever more encompassing and further reaching arguments against it has, by way of passion-fueled hyperbole, unwittingly appropriated foreign perspectives, taking them afield too far. Even if most of their arguments are sound, as is common of men, and as has proven common of our people in the course of history, even those of us with the best intentions and a fair handle on Christian epistemology are not wholly immune to spurious arguments when they accommodate our own cognitive biases. Counting themselves Anti-Federalists from prior to the Constitution’s ratification, they have lately come to regard the Confederate cause of the mid-1800s as one and the same with the Anti-Federalist cause of the previous century. If the Union proved at length to turn despotic, some among them have resolved to blame the development of that tyranny on the founding covenant between the states.

Granted, the two are conceptually related, but certainly not the same thing. If they were the same issue, it would be surpassing strange that the Anti-Federalists of the founding generation played a key role in the formulation of the Constitution by drafting the Bill of Rights, and went on to become signatories to that document. Such was the case with respect to Patrick “give me liberty or give me death” Henry as much as Samuel “Christian Sparta” Adams. And once established, the Anti-Federalists and their descendants actually became the foremost defenders of the Constitution and invoked the same unceasingly in their opposition to later Northern usurpation in the run up to the war. And they persisted in constitutional ideals well after that conflict. Clearly, their righteous reservations concerning centralized power are codified in the compact itself; thus they felt justified in citing it for their defense. The 2nd and 10th amendments, among others, vouchsafe the righteousness of Southern secession. Indeed, the whole framing of said document upon independence from Britain by the same states as would later resolve to seek independence from the Union grants the Confederacy’s constitutional case whole hog. If the states had no God-given right of secession from the Union under the rubric of self-defense, neither had the colonies any such right before the crown. And if true for the former, it is only more so confirmed for the latter.

Blaming the Constitution for the Lincolnite revolution and reign of terror is to ignore the fact that Lincoln did all that he did in direct defiance of that covenant. For instance:

- His military blockade of Southern ports was an act of war. Under the Constitution only Congress could declare war, but Lincoln illegally circumvented them.

- Any congressmen who objected to his circumvention of the Constitution, such as Ohio Congressman Clement Vallandigham, was arrested and held without charges or trial.

- He shut down newspapers and arrested reporters who pointed out his unconstitutional acts. All in clear violation of the 1st amendment which he swore to uphold.

- He had Chief Justice Roger Taney arrested without warrant for ruling that Lincoln had violated the Constitution in his suspension of habeas corpus.

- He dispatched troops to enact door-to-door weapons confiscation in Maryland, contrary to the 2nd, 4th, and 10th amendments.

- He had Henry May, a congressman from Maryland – a Union state – arrested without warrant and held without trial for “suspicion of Southern sympathies,” and without charge.

- Likewise with the Maryland state legislature.

- And with most of the Baltimore city council.

- And with the Baltimore police commissioner.

- Likewise too with the mayor of Baltimore.

- And thousands of Maryland citizens besides.

– All of these were held in military prison camps without charge and without trial. - He issued the Emancipation Proclamation in violation of the Constitution and the Supreme Court’s decision on the matter.

- He had much private property seized for public use without compensation or due process of law, contrary to the 4th amendment.

- He routinely had prisoners tortured in violation of the 8th amendment.

- Article III, Section 3 of the Constitution defines treason as levying war against the states, which Lincoln did. Therefore, he committed treason.

- … et cetera, et cetera, ad infinitum.

Lincoln did not do what he did by powers granted him under the Constitution. He flouted it root and branch. So the fall of American society, inaugurated under Lincoln’s regime, continues on its downward spiral not on account of the Constitution, but entirely in spite of it. What a strange irony that Southrons should lately come to repudiate the Constitution in effect, because a Yankee dictator repudiated it in his lawless assault on their forebears who affirmed it. Strange beyond reckoning.

Nevertheless, it must be known that, as new as this whole approach to the subject is on the Right, it is only slightly older on the Left:

During the first decades of this century “debunkers of our national heritage,” as the first critics of the founding fathers were called, attempted to remove the haloes from around the heads of our country’s leaders during the 1780’s and 1790’s. Textbook history for them had become too much a story of national self-congratulation and too little an attempt at critical, constructive self-examination. This new generation of historians suggested that gods had not made manifest the Constitution of 1787, but rather men, human beings actuated by the temper of the times and their own human natures. In short, they argued that the founding fathers were men who could and did at times act out of normal human passions of self-interest and ambition. . . .

Historians now began to ask whether our early national leaders were also politically ambitious, self-interested, and motivated by economic considerations in their careers. In due time even the founding fathers and their work at Philadelphia in 1787 came under close scrutiny, and the debate started by these historians would not die down until almost our own time.

The opening attack against the founding fathers was launched in 1907 by J. Allen Smith in The Spirit of American Government: A Study of the Constitution. Smith claimed that it was not a forum of disinterested statesmen but “the property-owning class who framed and secured the adoption of the Constitution.” This elite, made up of southern planters and northern merchants, he argued, had become greatly alarmed during the 1780’s by the state legislatures passing laws in the interest of debtors instead of creditors. The country was largely in a state of depression after the Revolution, and in numerous instances the lower houses in state legislatures (elected annually by the people and responsible for initiating fiscal bills) had taken steps to relieve the distress of the common people. For example, stay laws were passed to prevent creditors from seizing the homes of those defaulting on their mortgages, and often paper money had been issued at an inflated value. Governors and elite groups in the states often found themselves confronted with legislative mandates and laws from which there was no recourse. Under the Articles of Confederation, the central government was so weak that it had virtually no control over the nation’s fiscal affairs or the powerful assemblies representing the people in the states. Smith, studying the backgrounds of the 55 delegates at Philadelphia, believed they constituted an economic elite. The new Constitution erected at Philadelphia greatly enhanced the fiscal powers of the national government, and so he concluded the founding fathers were acting out of natural, economic self-interest.2

If Smith’s 1907 introduction of the Marxist cash-nexus lens impugned the motives of the Founders by alienating the concept of property from their broader contexts of peoplehood and Christian ethics, he was forerunner to a more thorough deconstructionist, Algie Simons:

Where Smith had taken the first tentative steps towards working out an economic and political conspiracy thesis concerning the establishment of the Constitution, Algie Simons in 1912 presented this new interpretation quite forcefully, saying:

‘The organic law of this nation was formulated in secret session by a body called into existence through a conspiratory trick, and (it) was forced upon a disfranchised people by means of dishonest apportionment in order that the interests of a small body of wealthy rulers might be served.'”3

Though this new deconstructive theory, heralded by the arrival of Marxism on our shores, had little traction when first postulated in the early twentieth century, it would be popularized foremost through Charles A. Beard’s 1913 book An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States and adopted en masse by Liberal academics between the first and second world wars as the radical Left secured total hegemony over academia. By 1950 it was the consensus view of Leftist academia – just in time for the commencement of Gary North’s college career. And his twin emphases in college were economics and Western civ, the two areas of study most impacted by the Marxist reinterpretation of American history; so he was drowned in Leftist propaganda in precisely the areas of study where he would come to profess Leftist views. No coincidence, there.

Whether Mr. Weiland and those like him are aware of it or not, this is the pedigree of the narrative they now takes up: the ‘CONstitution’ argument has been predicated on and developed through a patently Marxist reinterpretation of our history.

That isn’t to say, of course, that profit motive or greed cannot be recognized in certain issues. Indeed, the Scripture confirms that “the love of money is the root of all sorts of evil” (I Tim. 6:10), and recognizing that certain parties may be animated by economic motives above religious, cultural, and moral ones is not the same as being a cash nexus theorist or a Marxist oneself. More plainly, to acknowledge the existence of economic Marxists doesn’t make you one of them.

I say that to preface this point: that though Confederate Christian scholars such as R.L. Dabney, who lived through the war and Reconstruction, did discuss the profit motive of the Bank of London in the slave trade as well as that animating the Yankees in some measure, they never denounced the Founding Fathers or the Constitution as an anti-Christian economic class conspiracy. No, it is clear that the ‘CONstitution’ theory came to America only on the tides of German-Jewish immigration which occurred primarily in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It made landfall with and was in fact promulgated by Marxists.

Realize that this perspective bestowed by Smith and Simons has subsequently been applied to all facets of the colonial era. Be it the Salem witch trials or racial segregation, otherwise known in PC vernacular as the “construction of Whiteness,” economic class struggle is now commonly ascribed responsibility for all. Theology, patriotism, and morality are from that vantage construed only as pretexts to monetary gain and self-interest, in turn proving that Christian civilization itself was but a crude product of social Darwinism all along. Obscene, I know, but this is the conceptual bailiwick prevailing now even amongst many erstwhile Rightists and theonomic advocates such as Misters North and Weiland.

Let my Confederate brethren recognize that the cash nexus, Illuminati ‘conspiracy in Philadelphia’ perspective has, based on all the same arguments, been turned on the Confederacy with equal force and for all the same reasons. Because up to, throughout, and after the war the Confederates championed the Constitution against its Yankee defilers.

However, even those Confederates who have unwittingly taken a Marxian frame of reference on the subject lately yet employ those assumptions to very different ends: rather than repudiating the ‘CONstitution’ for its entrenched inequality, the suppression of democracy, and the establishment of “institutional White supremacy,” as Leftists do, Mr. Weiland and co. argue just the opposite – that the Constitution guaranteed the eventual abolition of all those things. As they tell it, Americans’ having succumbed to the moral rot of Liberalism proves the Constitution was a false system apart from God’s law. Else, if the Constitution were sound, the republic it founded would have remained forever, and the people would have been nurtured by it into ever greater sanctification.

But this argument is false on its face, lying somewhere between the logical fallacies of cum hoc ergo propter hoc and post hoc ergo propter hoc. Neither the correlation between the Constitution and modern America, nor America’s eventual degeneration, prove any causation. For if granted, it would prove entirely too much. This line of reasoning would invalidate not just the constitutional republic in the New World, but literally every government in history, including all those founded by Christians, and upon the most theonomic premises. If we rebuke the Constitution for a lack of durability, we equally indict the Puritan commonwealth, the Old Dominion of Virginia, and the Articles of Confederation which preceded it – not to mention the United Kingdom which, incidentally, CIs (inclusive of Weiland’s British and/or Anglo-Israelism) have historically regarded as a divinely sanctioned government subordinate to their Lia Fáil–Stone of Destiny narrative. If the constitutional republic in America is invalidated for its common law extensions of biblical nomology, the British monarchies fall with it, and for not only the same reasons, but even more, as the doctrine of the divine right of kings originates in papal dogma and paganism, rather than God’s Law.

Moreover, did not the original Israelite republic founded in the books of Deuteronomy and Numbers fall too? If governmental structure were the panacea for the total healing of society and the perpetuation of the righteous community, the establishment of the Israelite republic under the prophetic authority of Moses and Joshua, and thereafter upheld by the administration of the judges, should have lasted forever and raised the people to righteousness in perpetuity. But it didn’t. Because it couldn’t. This is simply not the telos of the magistrate. The Law does not redeem men’s hearts, so a sound legal and civic structure cannot prevent apostasy. That is the realm of saving faith in Christ, inclusive of His perfect law-keeping on our behalf.

If the nation-state of old Israel established under the circumstances of direct prophetic oversight failed to produce the sanctified and everlasting state which Mr. Weiland insists true Theonomy would produce, the issue is insurmountable. And the standard to which he subjects the Constitution, then, is clearly mistaken.

In his crowning work, Lex Rex (“[God’s] Law and the King”) – a work held dear by the majority of America’s founding generation – Westminster divine Samuel Rutherford expressly refutes Weiland’s idea, saying that since all government among men is vested by God rudimentarily in the agency of the people themselves, all civil government is subject to the suffrage of a given people.

The kings of Israel . . . were made kings by the people, as the word saith expressly . . . by this medium, viz., by the free choice of the people. (p. 10)

A community [of families] . . . have a perfect liberty to choose either a monarchy, or a Democracy, or an Aristocracy [Republic]. . . . Israel did of their own free will choose the change of government. (p. 29)

A community of families . . . may choose any of the three. (p. 30)

In context, Rutherford was not arguing for some libertarian will to power or sanction of legal positivism drafting law out of the imagination, but rather, as explicitly defined for nations in Scripture; and that against the usurpations of foreign governmental bodies such as the Scots and the English were facing under the Roman Magisterium.

Though the prophet Samuel warned Israel severely against their revolution in laying down the theonomic republic for monarchy (I Sam. 8), and God describes this as their having rejected Him as their king, it is from the old Latin texts of this exchange whence Western political science would appropriate the phrase “vox populi.” God instructs the prophet to “heed the voice of the people” (8:7). Though God’s Law and His Kingship are the inarguable mandate of heaven, top-down imposition of that order contrary to the plebiscites of the people themselves cannot sustain it in fact, because the very nature of the theonomic republic instituted under Moses is a decentralized minarchy dependent upon the bottom-up commitment to that order on the part of the people themselves. If the people do not believe in it, or are unable to self-govern under God’s Law, a decentralized magistracy cannot persist, as its free character itself will be regarded by its slavish people to be a tyranny by neglect. The liberty associated with it is exactly coordinate with the degree of personal responsibility in the spirit and capacities of the people, things which simply cannot be legislated into being or compelled by statute. For any government to maintain the liberty of a folk unsuited to it is not at length possible, as they will regard that freedom as tyranny and in the name of ‘freedom’ and ‘justice’ beg for tyranny. More than begging in fact, they will subvert, usurp, and supplant any righteous state from within. So it was that Israel demanded centralization under a human king. And there was nothing to be done about that so long as the people themselves lacked the moral integrity to live free and independent under God. As grievous as this reality was to Samuel, God told him there was no recourse but to heed the vox populi. To the extent that a people refuse the direct rule of God the apparata they erect against it are but gallows for their own judgment.

Rutherford’s point is not to vindicate democracy. Rather, it is to explain that all governments among men stand or fall by the character of the people.

We have watched this dynamic play out in modernity, as what we all recognize for terribly flawed systems of government and economics prove sustainable relative to the temperaments of the people: Swedish socialism, for instance, became the posterchild of Leftist success in the minds of Liberals everywhere. Whenever a Conservative anywhere denounced statist-socialism, Liberals were keen to invoke the socialist Camelot of Scandinavia. But the durability of each northern European Xanadu proved to have a very specific threshold: their utopias persisted only so long as they remained racially homogenous. Prior to the immigration tidal wave Swedish socialism managed to work only because it dealt with Swedes; for even if that system would have offered robust financial support to any Swede who opted to spend his days lounging about on street corners, that circumstance is so contrary to basic Swedish character that public resources were scarcely abused in such ways. But upon introduction of Africans and Arabs to that country, a large percentage of whom, and quite contrary to the nature of their host nation, simply refuse to work, those resources were suddenly consumed by the immigrant populace at rates unfathomable to ethnic Swedes. Swedes were a people who instituted a nanny state without needing or utilizing it, but that dynamic does not pertain universally to the character of every folk. If the character of the people be high, they may make a highly imperfect system work surprisingly well; but if their character is low, the best system in the world shall not suffice to preserve them. Hence the old chestnut, “Every country has the government it deserves.”4

But as we all know, if homogenous Scandinavian socialism seemed to work for Scandinavians, it also bore within it the assumption of absolute egalitarianism – the very thing which would open the gates to invasion by peoples unsuited to that cohabitation. So while Scandinavian socialism may work with Scandinavians, its presuppositions necessarily lead to an erasure of Scandinavians themselves, thus bringing to a rapid end all seeming success in their system of government.

As we’ve said, even the direct administration of the theonomic republic did not secure the hearts of the people in Israel, nor even the perpetuation of its own operation. But that was not an error in the system. It is a fault in men which can only be restrained by personal adherence to God’s Law and Gospel. Thus did John Adams say, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Congruent then with Adams’ words, American history from the 1860s forward has been a steady stream of law redefined, abolished, or, as in the cases of blue laws and sodomy laws, simply ignored. Because the Christian faith which undergirt the founding generations has precipitously slipped away, founding covenant and procedural safeguards notwithstanding.

Moreover, if Conservatives have always denounced the notion of the perfectibility of man via the top-down social programming professed by secular administrator types, how shall we do less when advocates of God’s law functionally don the same perspective? It is apparent that Weiland’s expectations of civil government overflow the bounds of nomology and civics into the realm of soteriology: by preaching a theory of the polis as panacea to the human condition, he presupposes the perfectibility of man through the therapeutic state. Even if he rightly lobbies for God’s law, I regret to say that he has misconceived the mechanism of corporate sanctification. His top-down administrative view of society has historically been the perspective not of Theonomists, but of social gospel advocates, and utopians of every sort. Even if pursued under the auspices of God’s Law, he envisions its institution under the rubric of statism, which is contrary to that very law.

Of the revolutionary coups in Israel’s early history, there were the recurrent turns toward statism wherein the government came to be seen, in Hegel’s terminology, as “God walking on earth.” But the other signal revolution, while maintaining cognizance of the difference between God and the state, was nonetheless seduced to centralization under monarchy. Though there is a distinction between monarchy and god-state, the Scripture discerns it as the difference between declension and open apostasy, because a monarchy can yet hold kings under the Law, as in constitutional monarchies, and therefore under God. But should a monarchy embrace the pagan doctrine of the ‘divine right of kings,’ as was the rule in the Orient, and as would later appertain in fits and starts in Europe, it descends into lawless autocracy and absolutism, the arbitrary god-state tyranny known biblically as Baalism. All of which CI ministers have traditionally acknowledged as much as any orthodox denominations.

To ultimately understand the American Republic and her Constitution, one must take them in context. Even if it is now denigrated as merely one ‘perspective’ amongst others, originalism is simply the acceptance that the Constitution has a finite meaning – the circumscribed intent of its authors. And that may be comprehended only by the explanations, references, and usages of the same. Absurd as it is to entertain any alternate interpretations of the Constitution, the “living Constitution” school has driven all regard for the compact’s actual meaning from the institutional seats of power.

Because at root, originalism presupposes not only the internal coherence and finitude of the Constitution, but a certain ontological coherence back of it which descends conceptually directly out of the biblical hermeneutic, the analogia de fide. As such, it relies upon epistemological realities irreconcilable with the open-ended ambitions of statism. Thus, for the god-state to rise, originalism had to be interred as a dead letter.

The Text of the Preamble to the Constitution

We the people…

The word ‘people’ is not to be defined in the terms foisted on us by nineteenth and twentieth century socialism in slogans such as “power to the people” – or songs – which reconstrued the term ‘the people’ as its antithesis: a repudiation of the European stock of America’s founding. No, there is no mistaking the identity of ‘the people’ addressed in the preamble because it goes on, in the same sentence, to describe them as “ourselves and our posterity.” This is in keeping with the Declaration of Independence, which invoked the rights of “consanguinity” with the English against the “Indian savages,” as well as John Jay’s description of Americans as all being descended from the same ancestors and being very similar in religion and custom. And as if all this were not enough, the founding Congress clarified the identity of the people beyond all dispute as “free White people” in the Naturalization Act of 1790.

This conception of nationhood is the same argued for long beforehand in the Declaration of Arbroath as much as Rutherford’s Lex, Rex. Both of which assumed the biblical standard of nationality – ethnos and genos.

And if any would suggest that the article were flawed on account of opening with reference to men rather than to God, we might compare it to the introduction to that overtly Calvinist compact, the Solemn League and Covenant:

We noblemen, barons, knights, gentlemen, citizens, burgesses, ministers of the Gospel, and commons of all sorts…

Likewise, the Mayflower Compact opens:

We whose names are underwritten…

And Magna Carta (1215) begins:

John, by the grace of God king of England…

So too with the Constitution of Virginia (1776):

A declaration of rights made by the representatives of the good people of Viriginia…

And the Articles of Confederation, which many Rightist subscribers to the ‘conspiracy in Philadelphia’ idea hold sacrosanct, began thus:

To all to whom these Presents shall come, we the undersigned Delegates of the States affixed to our Names send greeting.

It is then evident that the political covenants of Christendom have tended to follow a like pattern of approach, identifying the testators at the outset of each instrument. This pattern in Western civics follows the ecclesiastic rulings definitive of trinitarian orthodoxy such as the Definition of Chalcedon (AD 451) which begins, “Following, then, the holy Fathers, we all unanimously teach…” And back of that of course, is the first of such statements – the Apostles’ Creed: “I believe…”

Which is to say that the body of our civic and political creeds in the West is the public outworking of ethics which has blossomed from the root of our religious credo itself. This conceptual lineage is not incidental, but an ever-present and recapitulated acknowledgement by our fathers of the fact that all government is religious and undergirt by faith. And the legacy of Western law stems from the Christian faith in particular.

This is all the more underscored by the language of “a more perfect Union” invoked in the preamble. Though Lincoln would misconstrue it terribly by teaching that the states were the product of the Union under the federal government, the Founders’ reference to union communicates exactly the opposite: they were speaking the language of the Articles of Confederation, the preamble to which not only describes the “perpetual union” of the states as by voluntary and independent compact of those states for their common defense, but even speaks of “Americans” as a nation pre-existing said compact! Which is to say that the propositional nation imagined in the Gettysburg Address – of a federal government creating or constituting a nation is an overt denial of the self-identification of our fathers in this land from colonial times up through the founding generation, and even up into the mid-twentieth century, as was evident as recently as the case of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind.

But inasmuch as the Constitution’s reference to union had its antecedent in the Articles of Confederation, both were predicated upon the very recent context of the English Revolution, which had formed the United Kingdom by way of the Solemn League and Covenant. This kingdom would become the United Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland under the administration of one who refused the title of king – Oliver Cromwell – in deference to the biblically prescribed civics of a theonomic republic a la Moses’s books of the Law, Joshua, and Judges. With all this in mind, the executive office in American civics would be titled “president.” Because we followed the theonomic principles of the Presbyterian and Puritan roundheads in proclaiming, “No king but King Jesus!” A ‘president’ was a chief minister or presbyter, but in the context of civil government, he “is the minister of God, a revenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil” (Rom. 13:4).

This was the context out of which Americans took our conception of republican union – Theonomy as it had been so arduously worked out in the British Isles up through the Reformation. Yes, we understood God’s Law and its establishment of the nation-state of ancient Israel, as well as New Testament creedalism, as mutually reinforcing and interlocking halves to the whole for godly civil government, thus producing the constitutional republic. Thus making the language of the preamble of one conceptual cloth with Cromwellian Theonomy. This is why the battle cry of the American War of Independence was “No king but King Jesus!” It is also why King George would refer to that war as “the parson’s rebellion” and “the Presbyterian rebellion.”

What’s more, the preamble’s reference to “blessings” of the things therein “ordained” is blatant benedictory language. Indeed, the secular humanist mind rages because they too recognize any talk of ordination as distinctly religious.

Article 1, Section 1

Out of the gate we come to a structural question. Fellows such as Mr. Weiland have found it easy enough to point out that the words ‘congress,’ ‘senate,’ and ‘house of representatives’ are not found in Scripture, and that God is the only true Legislator. All well enough true. But as every trinitarian knows, no matter how much gusto someone levels the “that word doesn’t appear in the Bible” argument, it is a spurious standard. Just as with the term ‘Trinity,’ Latinate Anglo-Saxonisms such as ‘legislature’ were always understood as born of the biblical civic structure which emphasized rule by elders in Old and New Testaments. Though this principle of rule by elders is ubiquitous in Scripture, the formal and forensic arrangement of those conclaves, be it in Sanhedrinal committees of seventy, or proportional representation of tribes and families, is not specified.

But neither does the Scripture impart any explicit procedural standards, only general calls for things to be done “in good order” and principles (such as the golden rule) which in the course of time Christendom has refined into procedural practices by “good and necessary consequence” from the text. Though there have been a few permutations of parliamentary procedure adopted by Protestant republics and denominations at different times, our Presbyterian and Reformed churches have for some time found the iteration known as Robert’s Rules of Order most profitable for the deliberation of church business.

These things – legislative bodies such as the House of Lords and the House of Commons or Congress and Senate – have also, irrespective of their differing nomenclature, been found, under the circumstance of their time and place, necessary outworkings of biblical principle.

All of this is passed down in Christendom from the template of the historic councils of the church, all the way back to the Jerusalem Council recorded in the book of Acts, as well as the general call for the people to identify and electorally set natural elder-representatives over our tribes (Deut. 1) and Christ’s Church.

As regards Mr. Weiland’s protestations against the concept of man-made legislation, he must ignore the entire conception of law under which our republic was founded – the Christian common law. Of which Rushdoony has said, “[C]ommon law is essentially Biblical law.”5

The Commentaries on the Laws of England by Blackstone are characterized by historian Daniel J. Boorstin thus: “In the history of American institutions, no other book – except the Bible – has played so great a role.”6 In Blackstone’s introduction to his commentaries we read:

The doctrines thus delivered we call the revealed or divine law, and they are to be found only in the holy scriptures. . . .

Upon these two foundations, the law of nature and the law of revelation, depend all human laws; that is to say, no human laws should be suffered to contradict these.

It has been noted that in the era of America’s founding all homes had a Bible, but next to Scripture in popularity was Blackstone’s Commentaries; and that followed by Rutherford’s Presbyterian law book, Lex, Rex, and Bunyan’s Puritan work, Pilgrim’s Progress. These works framed the popular milieu.

American law and civic structure was from the beginning self-consciously based in Protestant – that is to say Calvinist – which in turn is to say theonomic – deontology. Law was, in Blackstone’s reckoning, a thing not to be created, only discovered. Despite modernist descriptions of American institutions as experiments in positive law, American law was never fiat in nature, as Americans reviled the very notion of legal innovation, insisting instead on organic application of God’s law through Christian conscience to men’s particular and regional concerns. And this, of course, comports with the case laws of Deuteronomy, which act as the template for the stare decisis of common law. Which explains how Tocqueville could summarize our civics in such theonomic terms:

In America religion is the road to knowledge, and the observance of the divine laws leads to civic freedom.

Article 1, Section 2, Subsection 1

The concept of a delegation of representatives chosen by the plebiscites of their people is a resolve which long precedes the American context. Not only did the Westminster divines teach just this view, they did so emphasizing that it is the patent teaching of Scripture; for even under the de facto circumstance of monarchy in his day Rutherford taught:

[N]o man can be formally a lawful king without the suffrages of the people. . . . Saul was no king, till the people made him king, and elected him king . . . never a king till the people made him so . . . there floweth something from the power of the people. (p. 9)They were made kings by the people, as the word sayeth expressly . . . by this medium, viz., by the free choice of the people. (p. 10)

[T]his law of the people is prior and more ancient than the king. . . . That which taketh away that natural aptitude and nature’s birthright in a community, given to them by God and nature . . . is not to be holden. (p. 43)

Rutherford took the state of society under the old Israelite republic as the default society of men under God: a decentralized patriarchal clan society in which power was vested by God in the families themselves, who in turn (per Deut. 1 as well as all the pastoral letters of the NT) are obliged to identify and raise their own natural elder-representatives from their midst to rule over them.

This is precisely what obtained in varying capacities from Calvin’s Geneva to Cromwell’s England, from old South Africa to America.

Term limits are but the hard-proven check against total depravity to which our Reformed fathers found themselves compelled in the English Revolution against Charles I. In keeping with the Reformed doctrine of the lesser magistrate, our fathers found the responsibility to defend the nation and their own families to supersede the offices of the magistrates, as the people have a duty under the sixth commandment to safeguard their own lives and those of their neighbors from tyranny and the threat of democide: “Thou shalt not stand by the blood of thy neighbor” (Lev. 19:16). Seeing as how King Charles was one in a string of kings who colluded with the Roman empire to the point of prosecuting genocidal war against his own folk, and under the circumstance of their unimpeachable titles his vested noblemen, too, proved so easily bent to the same treason against the nation, the process of Reformation in England deeply impressed upon our fathers the need for hedges against such evil. In keeping with orthodox Christian anthropology, the moral frailties of fallen men made lifetime appointments to certain levers of power, such as under monarchy and hereditary titles, a clear and present risk to life – even to the life of the nation itself – as well as to the Christian religion among them. Since all our Reformed fathers recognized the principle of “good and necessary consequence” in exegeting Scripture (WCF 1:6), safeguarding the life of one’s neighbor as well as that of his own house, and true religion amongst all, God’s Law necessarily implied to the minds of our wise fathers the mandate of term limits, among other such checks on power – if not to wholly thwart, then at least to mitigate the damage which proved inevitable under monarchy. In the context of the Founders’ immediate history, term limits were the expression of biblical law applied, allowing for peaceful remedy to circumstances which had proved otherwise to come to catastrophic bloodshed for lack of such provisions.

Article 1, Section 2, Subsection 2

Restricting eligibility of representatives to certain minimums of age is clearly assumed in the perennial biblical language of “elder.” Since the Scripture does not specify any particular age at which one may suddenly be deemed ‘elder,’ we have to define it somewhat by reference to its opposite: clearly, even if married, a fifteen-year-old would not satisfy the definition of ‘elder’ in anyone’s mind.

Though it may be a seemingly arbitrary means of safeguarding fidelity on the part of prospective representatives, setting a minimum duration of residence – in this case, a seven-year period of perfection, hinting strongly at numerous biblical probations – goes some ways to ensure a degree of rootedness within the jurisdictions of a given state. In the colonial context, this most closely approximates the biblical injunction that our leaders must arise from amongst our own tribes (Deut. 1:13). Particularly because that stipulation of rootedness functions in tandem with the assumption of freehold suffrage: from the earliest times in America – at least 1676 onward – the franchise was officially limited to free, landed White males over the age of twenty-one. But the age of twenty-five in particular is the same as listed in Numbers 8:24 as the time at which a Levite might ascend to office to represent the people before God: “This is it that belongeth unto the Levites: from twenty and five years old and upward they shall go in to wait upon the service of the tabernacle of the congregation.”

Consider the correspondence: “The Levites are to be responsible for the care of the tabernacle of the covenant law” (Num. 1:53). What is a priest, after all, but a representative of the people appointed to the ministrations of the law on their behalf? An office warranted both by biblical example and needfulness, these biblically literate men had warrant to say, “It seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” (Acts 15:28) to set a minimum age requirement which corresponds precisely to a biblical office, per Numbers 8:24.

Article 1, Section 2, Subsection 3

The question of proportionality of representation being needful to any genuine representation is apparent, else whole districts of counties would find themselves bereft of a voice for the local administrations of law. This sort of populist representation, too, has precedent in Scripture:

So I took the leading men of your tribes, wise and respected men, and appointed them to have authority over you – as commanders of thousands, of hundreds, of fifties and of tens and as tribal officials. (Deut. 1:15; cf. Ex. 18:21-25)

Though Moses ‘appointed’ these elders to their offices, the proviso that they must be deemed ‘wise and respected’ immediately implies some system of voting on the part of the people to identify their natural aristocrats in order for Moses to vet them. Under apostolic administration the same is reiterated, but moves the question of plebiscites from implicit to explicit:

So the twelve summoned the whole multitude of the disciples and said, “It is not desirable for us to neglect the word of God in order to serve tables. Therefore, brethren, select from among you seven men of good reputation, full of the Spirit and of wisdom, whom we may put in charge of this task.” (Acts 6:2-3)

The command to ‘select from among you’ may, without the slightest damage to the language, be translated ‘elect from among you.’

The exclusion of Indians from representation was in keeping with the biblical definition of nationhood. A race apart from us, they have no rightful voice in our government. Once again, per Deuteronomy 1:15-16, the Christian ideal of leadership is one of natural elder-judges born from amongst our own tribes who will in turn judge between their brethren and the stranger in our midst.

The provision for “free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years” is congruous with the biblical allowance for terms of bonditure, as both Scripture and the Constitution take for granted that they remain “free” in the sense that their term of service is limited. In America, as in the Israelite republic before, we maintained a tiered system of domestic bonditure in which bondsmen of our own race – the Irish and poor Northern British in large numbers – might be held for a seven-year term (cf. Ex. 21:2; Deut. 15:12), which Jeremiah underscores with an admonishment to Israel to do better than their ancestors in this regard: “‘Every seventh year each of you must free any fellow Hebrews who have sold themselves to you. After they have served you six years, you must let them go free.’ Your ancestors, however, did not listen to me or pay attention to me” (Jer. 34:14).

From the earliest colonial times – and still well within the Reformation era – the British, in keeping with the aforementioned biblical codes of bonditure capped spans of servitude for Whites at the seven-year marker. “By contrast, Virginians usually made lifelong slaves of Africans and their progeny, beginning in 1619.”7 And this practice was entered into consciously in fidelity to God’s law around slaves of foreign races, which the Scripture granted as “perpetual slaves” (Lev. 25:44-46). At the time this was equally the perspective of New Englanders as much as Virginians.

So committed are Leftists to the narrative of outrage at past Black servitude, that they either intentionally misinterpret the representational apportionment of the Three-Fifths Compromise for ‘all other persons’ to mean that the Founders regarded Blacks as less than human. Either that or they simply cannot understand the language. Or a little of both.

No, it does not mean Africans were deemed 3/5ths of a person. Just the opposite, the language of the provision explicitly acknowledges their full personhood, conceiving them part of ‘all other persons’. The 3/5ths mentioned is descriptive of their apportioned representation, not their personhood.

As a covenantal compact between independent states following the pattern of the Solemn League and Covenant before it, certain countervailing geographic interests had to be ameliorated by some sort of compromise. Our fathers’ resolution was a certain disproportionate representation on the part of the slave-holding states. Inasmuch as Christians had always understood the relation of a master to his slaves to be implicit somehow in the fifth commandment regarding honor due to parents, the Southern states were understood to be ward of a secondary population under some category of paternal oversight, not unlike children. Hence the now sullied term, “paternalism.” But because they were not heirs of the people, the apportionment of representation could not be full. The question of the appropriate ratio then was, then, left to a relative estimate of equity and expedience. This has been the manner of all treaties, compacts, and covenants of Christendom in some measure. Matters of equity and proportionality are always subject to myriad clauses and provisos as much as it is to basic mathematics and the relative tongue of those entering into covenant. Biblical law does not prohibit consideration of logistics. On the contrary, it provides the only just framework for their consideration.

The people who would have us scuttle the Constitution on account of points such as this would, on the same grounds, do likewise with everything from the Mayflower Compact to the Magna Carta. Disallowing all such circumstantial applications of biblical law, they would have us repudiate the last two millennia of exegesis whole cloth, and leave us to begin the process of building Christendom again from the beginning. Not only is their conclusion unnecessary, it is by definition a declaration of war upon Christendom as built by our sires, who though asleep in Christ, yet live; and who, as a rule, were much wiser and more righteous than we.

Beyond the question of proportionality, however, is the base question of taxation. This is a matter about which Theonomists have always been at loggerheads with one another. Some have made the case from certain Scriptures that alongside a tithe to the temple and priests, and the tithe to the poor, there was a tithe to the judges and elders as well. Granted, I’ve generally taken Christ’s discussion of taxation with Peter to conclude the matter:

And when they were come to Capernaum, they that received tribute money came to Peter, and said, Doth not your master pay tribute?

He saith, Yes. And when he was come into the house, Jesus prevented him, saying, What thinkest thou, Simon? of whom do the kings of the earth take custom or tribute? of their own children, or of strangers?

Peter saith unto him, Of strangers. Jesus saith unto him, Then are the children free. (Matt. 17:24-26)

Even if we see in this a rebuke against all direct taxation in favor of international tariffs for material support of the state, the exegetical disagreement amongst Theonomists has been intractable. Though I personally believe the Constitution is imperfectly organized on this point, a broad majority of God’s Law advocates yet stand opposite, insisting that Theonomy mandates, or at least allows for, direct taxation so long as those against whom a tax is levied are both the ones to vote it in or out, as well also the beneficiaries thereof. Such as in regard to the raising of armies in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 12, which allows for the levy of a tax should the people (via their representatives) deem it temporarily necessary.

Be that as it may, we do not here seek to prove that the Constitution is flawless or divine, only that, as Keeton has said, “The judges of earlier times spoke with a certainty which was derived from their conviction that the Common law was an expression of Christian doctrine, which none challenged.”8

Just as with instruments like the Westminster Confession and the Apostles’ Creed, our Constitution is predicated upon applications of biblical principle and subordinate to Holy Writ.

Article 1, Section 2, Subsections 4-5

These policies are also procedural in nature, like unto the various parliamentary rules of order by which our Western governments, denominations, and town hall meetings are conducted. As covered, these are logistical iterations arising out of the apostolic commendations to do all in good order, and with reference to the golden rule.

According to historical witness, these things were affirmed in our Continental Congress with Bibles open: “[I]t is the duty of all to acknowledge that the Divine Law which requires us to love God with all our heart and our neighbor as ourselves, on pain of eternal damnation, is Holy, just, and good. . . . The revealed law of God is the rule of our duty.”9 The above description typified the rituals of the Founders under the guidance of John Witherspoon.

Those who would cast the American founding as a secular experiment like unto the French Revolution are quick to point out the resemblances and citations of Locke’s and Montesquieu’s writings on independence and “checks and balances” as proof of that thesis. We concede to our Founders’ citations of said men, but the citation of Jacobin-leaning Liberals, when counterbalanced against the Founders’ copious citations of Burke, de Maistre, Rutherford, et al., demonstrates that they believed all of these to be sipping from the same well of principle, albeit in varied degrees of purity. Whether or not Montesquieu was an orthodox Christian, his writings are awash in the language of Christianity, and his technical observations on the structure of equitable government are only what they are because of the rubric of Christian tradition amidst which he was born. This he very much acknowledged, writing, “The Christian religion is a stranger to mere despotic power. . . . It is the Christian religion that, in spite of the extent of the empire and in spite of the influence of the climate, has hindered despotic power. . . . We owe to Christianity a certain political law; and in war, a certain law of nations – benefits which human nature can never sufficiently acknowledge.”10

Beyond his copious endorsements of Christianity as divinely revealed, and the signal force for the civilizing of men, he even affirms biblical law as superseding all human positive law. While he does entertain the Jacobin discussion of ‘man in the natural state,’ he predicates that discussion entirely upon the Genesis account of Adam and Eve in Eden. Really, were he alive today Montesquieu would be decried for a right-wing Christian extremist by the same people who otherwise cite him as a secular Leftist now. And as Francis Schaeffer famously argued in A Christian Manifesto, Locke’s work was but a retread of Rutherford’s Lex, Rex, though with most scriptural references omitted.

Our Constitution’s myriad restraints on power by dispersion and decentralization – concepts very much present in Montesquieu’s writing – were couched in decidedly biblical principle and tradition. As such his civics evidenced no small correspondence with Presbyterian ecclesiology into which the founding generation of Americans were born. Thus they saw no conflict in referencing the essays of Montesquieu alongside Presbyterian sermons, canons of common law, and Scripture. So when Donald Lutz confirms that Montesquieu sits right beside Blackstone as the authority most oft quoted by the American Founders behind the Bible,11 it makes a good deal of sense.

God’s Word was the common primer by which the Founders and men like Montesquieu became literate and on which they were reared. It formed their very language and framed all their categories of thought. If secularists are quick to point out that the separation of powers between judicial, legislative, and executive branches come not of God’s Law, but from Montesquieu’s work in The Spirit of the Laws, the very same demarcation of powers was outlined by the prophet Isaiah long prior: “The Lord is our Judge, the Lord is our Lawgiver, the Lord is our King” (Isa. 33:22). But the secularists assure us that is entirely coincidental.

Article 1, Section 3, Subsection 1

The word “senate” (senat in Middle English) is old amongst us, entering the English language between 1175 and 1225 A.D. It came down to us from the old Latin senatus: literally, “council of elders,” from senex “old man.” This senatus then, is the conceptual equivalent to the witenagemot, a “council of wise men,” which came to be known as the British House of Lords and broader Parliament; but it is yet more precisely equivalent to the biblical term presbyteros. As all our Founders were not only Anglophiles by descent, but, as was common throughout the Reformation era, classical Latinates by education, they knew this term ‘senate’ to accord exactly to biblical mandate and, by established Protestant usage, to ‘rule by presbyteroi.’ Eerdmans Bible Dictionary even translates the terms used for councils of presbyteroi as nothing less than ‘senate’:

In a few cases, other words are substituted for synedrion, e.g. presbyterion, ‘body of elders’ (Luke xxii. 66; Acts xxii. 5), and gerousia, ‘senate’ (Acts v. 21) . . . The councils (synedria) of Mt. v. 22, x. 17; Mk. xiii. 9, and the boulai of Jos., Ant. iv. 8. 14, etc. were local courts of at least seven elders, and in large towns up to twenty-three elders.12

Inasmuch as the old Hebrew council of the Sanhedrin is cognate with the Greek synedrion, and both mean, in essence, a conclave of elders ‘sitting together,’ both the Reformed church council known as synod and the civil office known as senate are derived from the same source conceptually and etymologically. The template was the apostolic councils, which were the but a continuation of the OT councils called synedrion, or Sanhedrin, in the Hellenic-Hasmonean era. All of which originated under the administration of Moses.

The American Senate was literally established as a civil presbytery, because the ecclesiastic organization of the New Testament is contiguous with the civil government of the Israelite republic. And because the NT speaks of civil magistrates as ‘ministers of God’ we see both institutions – church and state – are to be organized under a similarly authority structure.

Article 1, Section 3, Subsection 2

The division of the Senate into three tiered classes mirrors the distributed powers of the New Testament offices of deacons, ruling elders, and teaching elders. These strata exist for the same reason – to mitigate the danger of concentrations of power accruing to individuals.

We also recognize the insistence on a minimum age of thirty as keeping with the pattern of Scripture. In the first generations after Adam, thirty years old seems to have been normative marrying age. Joseph was elevated over Egypt at age thirty (Gen. 41:46). The primary body of priests entered service at age thirty (Num. 4:3). David’s kingship was confirmed at age thirty (2 Sam. 5:4). Ezekiel was called by God at age thirty (Ezek. 1:1). John the Baptist seems to have begun his work heralding the Messiah around age thirty. (This is likely as Luke 1 tells us John’s and Jesus’s mothers were pregnant with them at the same time, and John’s ministry coincides closely with the beginning of Christ’s.) And, of course, the exemplar of our Lawgiver – Jesus began His earthly ministry at thirty (Lk. 3:23).

Admittedly though, one third of the senate being made susceptible to deposal at every election cycle seems a redoubled safeguard against the entrenchment of a new unaccountable nobility as had obtained back in jolly old England; and against which our people had so recently fought a terrible internecine struggle for the English nation.

If not an explicit command in Scripture, it certainly does not contradict the Word. Rather, applied to the circumstance, these sorts of checks on power were implicit. So the checks on power peppered throughout our civic structure were not experimental, nor frivolous novelty, but the culmination of lessons learned in our own history under biblical law. Because lifelong appointment of rulers – a thing itself nowhere stipulated for magistrates in God’s Law – had oft proven too firm a concentration of power in the hands of men, and in practical experience, too consistent a threat to the life of the nation. Lifelong appointments as existed under the conditions of royalty had proven redundantly to not only endanger the God-given rights and lives of men and whole classes of men, but beyond this, the perpetuation of the Protestant faith and the very existence of the nations themselves. The many treasons of the Stuarts against the English people reached a level intolerable to Christian conscience when Charles I went so far as to issue death warrants for the people’s representatives in Parliament for the crime of upholding God’s Law over the arbitrary and cruel whims of the king; who in response would go and on to hire foreign Romanist armies to wage war on his own nation. All this was pursued with the clear aim of suppressing the Free English Church, which had been affirmed in Magna Carta as well as the councils of the Celtic See from the dawn of Christendom, and of bringing the English nation bound under the yoke of a foreign tyrant in the person of the pope.

Herein I have only undertaken to elaborate the theonomic assumptions of the Constitution in regard to Article 1, and that, not even in whole. Though we could easily proceed throughout the entirety of the Constitution in this fashion, to do so would amount to a lengthy book. Not that such would be an unworthy undertaking, but the purpose is served well enough, I think, by demonstrating the thesis in the portion which I have.

Objections

So if I am not to account for every jot and tittle of the Constitution, I will address some of the broad strokes which the Left, and more recently, the Right (ultimately following Gary North), have taken against her.

I) The Constitution doesn’t mention Jesus. Nor does it even offer any reference to deity generically.

This is false. Unlike the statements issued under the Jacobin revolution underway contemporaneous to the American War for Independence, our Founders insisted on acknowledging America as both an inheritor of and tributary to the Christian millennium by reference to the Christian calendar – “in the Year of our Lord.”

What Lord other than Christ might they have been referencing? It is an uncontested fact that this phrase was the English equivalent of the Latin anno Domini (A.D.) – ‘the year of His dominion’ – a denotation of time defined by its antecedent – “before Christ” (B.C.). Both of which were the common denotations of the Christian millennium from at least A.D. 525. The symbolism of which was so repugnant to the Jacobins that they made an overt point of renouncing all such language and reckonings of time in favor of starting the calendar over again at “Year One”; and that, to designate the “birth of Reason,” a purposeful replacement of the Incarnate Logos with carnal gnosis. The American Founders, though well acquainted with the Enlightenment arguments, spurned this Jacobin revolutionary sentiment in favor of continuity with and recognition of the Christian millennium. No slapdash fools among them, the Founders well conceived the meaning of their words here. Their reprisal of ‘the Year of our Lord’ counted Christ their Lord.

While modern Liberals may scoff at this as merely some throwaway colloquialism absent theological content in the minds of the Founders, we cannot help but note the same men typically insist on a sanitized denotation of time themselves – “Common Era” (CE) and “Before Common Era” (BCE). Because they, like the Jacobins of the sixteenth century, abjure the Christian millennium. Clearly, the Founders were not men such as themselves.

The Constitution’s reference to Christ defines America’s place in history, and as a Christian nation. Which is to say that America was defined in the context of Christ’s Kingdom.

Besides this, the ‘CONstitution’ interpretation, if embraced, here demands us to assume that the Founders simply did not mean at all what they wrote, but its exact opposite. Such a hermeneutic refutes itself.

II) The inclusion of a ‘Bill of Rights’ in the Constitution is anti-Theonomy because the Bible teaches no rights, only duties. The French Revolution introduced the idea of rights as the refutation of biblical law.

On the contrary, rights, liberties, and freedoms were principles native to Magna Carta, the Codes of Alfred, the common law, the Saxon codes, and even Brehon law well prior to and very much apart from the Enlightenment. By the time of America’s founding, purposeful explication and defense of the liberties of Englishmen, Welshmen, Saxons, Britons, Scots, and Irishmen already stretched back more than a millennium.

In America the Puritans had been stumping for their rights from the beginning. Be it the Massachussets Body of Liberties (1641), the Charter of Liberties of Pennsylvania (1681), The Mayflower Compact, or the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1638-39), the Puritans were insistent on rights no less than duties. Because our well established understanding of God’s Law from the time of the Reformation and prior was that each command imposes certain inverse corollaries: if “thou shalt not murder” any man, then men have a God-given right not to be murdered. This was the unquestioned understanding of the founding generation, reared as they were under the Westminster Catechism, which outlined sundry rights entailed in the Decalogue. Or as Bentham famously stated it, “Right, the substantive right, is the child of law.”

However, we must concede that certain noteworthy Conservatives such as Edmund Burke and Robert T. Ingram have occasionally repudiated the concept of rights in favor of duties. But we can acknowledge both at once, because the thing at which those Conservative were aiming in their rebukes of rights was a concept of the Enlightenment: the ‘rights of man’ and ‘human rights’ were originally crafted by the likes of Rousseau and Voltaire as repudiations of Christian law. To the extent that we might limit the conversation to that scope, we must rebuke rights; but that is a myopic approach which would disregard the otherwise ubiquitous acknowledgement of God-given rights from the Christian Weltanschauung throughout the history of Christendom.

III) The Founders were all deists who denounced orthodox Christianity.

This is absurd. Granted, there were a handful of the Founders whose commentary waxed and waned back and forth between Christianity and deism, yet the vast majority were solidly Christian. Even the two most notorious for their dalliances with deistic thought – Jefferson and Franklin – alternately affirmed trinitarian orthodoxy.

Though Jefferson implied himself to be a unitarian in his 6/26/1822 letter to Benjamin Waterhouse, and though he reported especially fearing the Presbyterians in his 3/13/1820 letter to William Short – or even though he defamed Calvinism as “Daemonism” in his 3/11/1823 letter to John Adams – he was yet a faithful confessing member of “the Calvinistical Reformed Church” when strict subscriptionism to the Reformed confessions was mandatory for membership. This Calvinistical Reformed Church convened alternately in the U.S. Capitol building and the Charlottesville Courthouse. Yes, the fellow hailed by the modern Left as the champion of the “separation of church and state” was a member of a church which tabernacled in the central federal buildings as the official spiritual guidance to U.S. statesmen. What’s more, he was actually one of the founders of said church! The Calvinistical Reformed Church was no anomaly; several churches – all Christian of course – convened in federal facilities, and none of the Founders imagined any conflict between that and the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, as moderns have come to allege. The fact that Congress opens each session with an invocation and that all her members are sworn in on an open Bible testifies to the essential character of Christianity in our form of government. Clearly, Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists assuring them of a wall of separation between church and state was not an endorsement of secularism, as Leftists have imagined.

In fact, it was a clear endorsement of the Protestant doctrine which Kuyper termed “sphere sovereignty.” Throughout Scripture God disambiguates ministers in the civic realm – judges, rulers, kings, magistrates, etc. – from ministers in the ecclesiastic realm – priests, presbyters, etc. – but all are nonetheless entrusted with the administration of God’s Law and reference to His mercy within their respective spheres. Even if Kuyper coined the term for it, the doctrine long preexisted his terminology and was well present in the writings of not only Calvin but many before him.

Jefferson’s spiritual status is complex. He cannot tritely be written off as a deist, as he wrote as much (or more) affirming orthodoxy as he did opposing it.

Ben Franklin was drafter and signatory to the Paris Peace Treaty of 1783, which concluded hostilities between the nations of Christendom “in the name of the most holy and undivided Trinity.” This, one of the foremost important resolutions of the founding American government, was conducted in the name of the Christian God. It cannot then be construed that the American republic was at the time imagined to be a secular Enlightenment state. Ben Franklin was not so committed to deism at that time as to demure from punctilious recognition of the Christian God. Nor was he disinclined to acknowledge America to be a Christian nation.

Albeit some may dismiss the Paris Treaty as written in the language of ritual and formality rather than true belief. This may be so, but could we imagine any comparably high-profile secularist – say, Richard Dawkins – drafting and signing such an oath? How about a high-profile practitioner of any other religion such as Islam or Judaism? Would anyone other than a Christian, or at the very least, someone conceding to the Christian foundation of law and society, ever lay his signet to such a statement? Frankly, it is doubtful that most who self-identify as devout Christians today would feel comfortable endorsing a civil document which upheld overt Christo-supremacy as the Paris Treaty did. Even if we granted that an unbeliever might concede to such central Christian truths in government, the Holy Spirit has clearly suppressed the evil in his heart for the sake of furthering Christian principle in the land.

So even assuming the presence of a handful of on-and-off deists amongst the Founders, it does not negate the orthodox Christian milieu in which they lived and from which they drew their principles of government anymore than Judas’s presence nullified the testimony of the apostles. If Franklin’s trinitarian oath laid to the Paris Treaty or his affirmations of the Constitution were in some degree disingenuous or based in a heterodox faith, they did not sully the content of those works nor negate the presumption of Christian law over the nations.

The vast majority of our Founders expressed no deistic bent whatever. They were catechized Presbyterians, Dutch Calvinists, and Congregationalists, mostly, reared on the Geneva Bible, the works of the Westminster divines, and the Three Forms of Unity. So it was that these same men drafted and approved Christo-supremacist anti-blasphemy codes, blue laws to hallow the Christian Sabbath, anti-sodomy laws, and the like – things which only Christian Theonomists would codify, and which are understood by none save Christian Reconstructionists.

IV) But the Bill of Rights enshrines a right to freedom of religion. This is an endorsement of pluralism and secularism. It therefore repudiates the First Table of God’s Law directly, and the second implicitly.

This is a major, albeit ubiquitous, misconception of the matter today. Due to its prevalence now I cannot wholly blame my Rightist friends for being befuddled over this point. But this too is a matter in which the Right has allowed the Left, who through the “living document” delusion otherwise claim the Constitution has no proximate meaning at all (a resolve to nonsense), to authoritatively define the First Amendment for them.

But it wasn’t always so.

So taken for granted was the Christian theonomic understanding of freedom of religion in 1838, that when one Abner Kneeland took to publicly writing and speaking in favor of pantheism that he was indicted for blasphemy. That text of indictment read that Mr. Kneeland was “willfully blaspheming the holy name of God” by denying that Jesus is God.

Kneeland’s case made of him a celebrity amongst the sparse unitarians and transcendentalists of the day, who contributed to Mr. Kneeland’s legal defense, both in rhetoric and finance. At trial the defense attorney for Mr. Kneeland argued that the anti-blasphemy laws of Massachusetts were invalid as they conflicted with the state constitution’s guarantee of religious freedom and the principle of a free press enshrined in the federal constitution.

The court responded with comparison to the laws of other states, wherein were found both assurances of religious freedom and anti-blasphemy codes side by side, just as was the case in Massachusetts, confirming that it was the common understanding that these things did not conflict. They also pointed out that the state anti-blasphemy law in question was, like in the other states, drafted and adopted close to the times of the religious liberty principle enshrined in their constitutions, as well as the federal constitution – and that in most cases, the same men had passed both. Thus confirming that the Founding Fathers themselves saw no tension between the concepts of religious liberty and anti-blasphemy laws to safeguard the Christian religion uniquely. Mr. Kneeland’s defense was thus laughed out of court as preposterous.

And only to doubly underscore the point, when Mr. Kneeland appealed the case, William Ellery Channing, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William Lloyd Garrison launched a petition for his release, arguing that Kneeland was being denied his right of free speech a la the First Amendment. Though it was signed by unitarians and transcendentalists, it didn’t do well at all with the mainstream public. When a counter-petition was launched reaffirming Kneeland’s guilt for blasphemy and apostasy, the signatories thereto were everyone but the unitarian and transcendentalist fringe. Kneeland served out his sentence of sixty days in prison.

Thus Justice Joseph Story would come to explain:

The real object of the amendment was not to countenance, much less to advance, Mahommetanism, or Judaism, or infidelity, by prostrating Christianity, but to exclude all rivalry among Christian sects, and to prevent any national ecclesiastical establishment which should give to a hierarchy the exclusive patronage of the national government.

Yes, contrary to the imagination of modern secularists, the neo-theonomists at American Vision, and Mr. Weiland, the religious liberty enshrined in the First Amendment never intended religious pluralism. For all their hyperventilation over the notion of multifaith or secular interpretation of the First Amendment, it just isn’t so.

While the concept of religious tolerance and free speech are taken for granted as the Protestant view since Luther’s apologetic for “liberty of conscience” at the Diet of Worms, neither Luther, nor Calvin, nor Zwingli, nor Knox, nor any other Reformer admitted non-Christian perspectives as inside the umbrella of that toleration. Luther himself never ceased inveighing against the Jew and the Turk (i.e. Mohammedan), and urged their suppression in and expulsion from every Christian land. The Reformers preached even the suppression of Anabaptists in society. The Reformers would have seen the notion of religious pluralism credited to them by their supposed mantle-bearers now as nothing less than apostasy.

But this history of Protestant toleration and liberty of conscience does inform the concept of religious liberty as it was assumed in colonial America. Hence the ubiquitous anti-blasphemy codes by which Mr. Kneeland was convicted:

Whoever willfully blasphemes the holy name of God by denying, cursing or contumeliously reproaching God, his creation, government or final judging of the world, or by cursing or contumeliously reproaching Jesus Christ or the Holy Ghost, or by cursing or contumeliously reproaching or exposing to contempt and ridicule, the holy word of God contained in the holy scriptures shall be punished by imprisonment in jail for not more than one year or by a fine of not more than three hundred dollars, and may also be bound to good behavior.