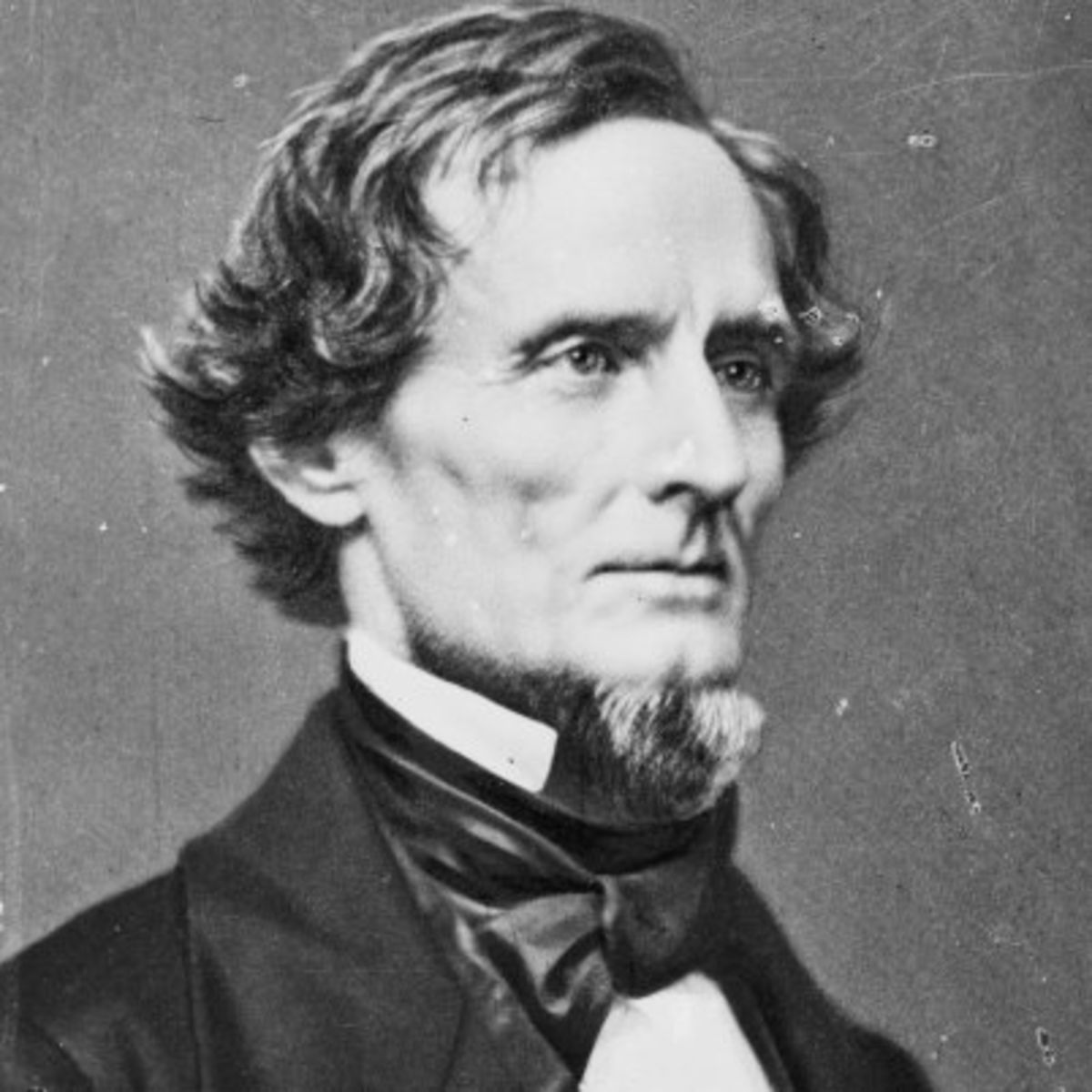

Once when living in California it was my pleasure to help with the dedication of an historical marker at an old church. After the formal speeches and such I chatted with one of the guests present. She remarked to me, “Did you realize this church was built when Lincoln was president?” I politely replied, “No, but it did cross my mind that it was built when Davis was president.” Well, not many folks may have been taught about Jefferson Davis during their school days in California, but nonetheless he was an “American” president. Of course, as president of the Confederacy he is more known in the South, and I was very pleased to learn, after my move to Mississippi in 2005, that he is honored here with a state holiday on the last Monday of every May.

Much can be written about Jefferson Davis. Although not born in Mississippi, he came to this good state as a small child when his father, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, became a planter near Woodville. Not only was he president, but he also represented Mississippi as a Congressman and Senator. Further, he held the cabinet position of Secretary of War in the federal government and was a colonel in the Mexican War, where he received much notoriety and fame for his bravery and leadership at the Battle of Buena Vista. Unfortunately a short column can’t give a complete biography of Davis. Still, something can be said, some insight into his beliefs and character can be given, to remind European-Americans, especially Southerners, to have pride in and honor him.

Like his father and his his elder brother, Joseph, Jefferson Davis was a Mississippi planter. Primarily he farmed a place called Brierfield Plantation near Vicksburg. As was common for most people of his time, he accepted the constitutionality of the institution of slavery. Unlike many people of the mid-1800s in these United States, including those in the North where many places wouldn’t even allow blacks to live, he had unusual views towards the treatment of his people on Brierfield. Davis, from the time of his youth, felt great tenderness towards people, especially those with the inability to fight back. As a result of these feelings, he never used corporal punishment on his slaves, which included prohibiting any overseer from whipping them. If one of his slaves was accused of inappropriate behavior, regardless of whether the accuser was white or black, Davis said of the accused slave, “I will ask him to give me his account of it. . . . How can I know whether he was misunderstood, or meant well and awkwardly expressed himself?” He even armed some of his slaves and led them against some lawless white neighbors. He treated his slaves with respect, allowed them to select their own names, gave many responsibilities and a measure of independence, made sure his slaves had religious instruction, educated many, and insisted, even to his economic detriment, that the health of his slaves be of more importance than his crops. One slave of his youth, Pemberton, developed a deep friendship with Davis. Pemberton was given authority over the slaves and was overseer himself at Brierfield. When discussing plantation business Davis often would give Pemberton a cigar, sit at the same table with him, and even bring forth a chair for Pemberton if needed. When holding public office Davis was gone often from his wife, Varina. Ordinarily in antebellum times, the wife would assume management of the plantation during the husband’s absence; however, Davis valued and trusted Pemberton so thoroughly that Pemberton, and not Varina, was left in charge. After Pemberton’s death Davis could never replace him as a friend or a manager, going through a seemingly endless string of white overseers.

Due to the high civic positions he held and because of the fame received at the Battle of Buena Vista, Davis assumed the informal leadership position in the South after the death of John C. Calhoun. He was widely read and educated. Certainly he understood the Constitution, and thus states’ rights, along with the history of the founding of these United States, which his father helped to form. He knew that, in his own words, the federal government had no natural authority: “It is a creature of the States. . . . As such it could have no inherent power, all it possesses was delegated by the States.” Davis understood properly that the Constitution guaranteed and recognized slavery. He made it clear that slavery was not the primary issue of the War Between the States, saying instead that the cause was “to totally destroy political equality. . . . The mask is off, the question is before us; it is a struggle for political power.” As a supporter of states’ rights and the Constitution, Davis understood that since the states formed the union with limited delegated powers, the states had the right to secede should the federal government attempt to dominate and exceed its delegated authority. Although he believed in secession, he was slow to actually support the secession movement and made attempts as a federal senator to compromise and resolve the differences between South and North. As Davis said, “I was slower and more reluctant than others. . . . I was behind the general opinion of the people of the State [Mississippi] as to the propriety of prompt secession.” When this became impossible, he accepted the presidency of the Confederacy when it was first formed and subsequently was elected to that position.

As president of the Confederacy Davis, like most Southerners, had no desire to fight the North or invade any Northern states. Rather, he wished to have good relations with them, their recognition of the Confederate States, and their promise of nonaggression. Some historians dispute this claim when they say that the South started the war when the Confederacy fired on Fort Sumter. It must be remembered, though, that the federal garrison there was ordered by the federal government not to leave even though the fort became the property of South Carolina upon its secession. Davis, of course, viewed it as an act of aggression when federal attempts were made to supply the fort. Yet, far from immediately engaging in battle, Davis sent commissioners to Lincoln to discuss the situation at Fort Sumter. As one historian writes, “As soon as Davis assumed direction of the Sumter matter, he decided on yet another commission to Washington. . . . Lincoln would not receive them and had little or no intention of negotiating.” After weeks of neither action nor reception, the commissioners and Davis understood they were being deceived; no meeting with the commission would take place, while instead the fort would be reinforced. Davis ultimately ordered the immediate evacuation of Fort Sumter, and in the event of noncompliance he ordered his batteries to open fire. As Davis said, “They have been trimming and blindfolding in Washington. . . . We have been patient and forbearing here. . . . Nothing was left for us but to forestall their schemings by a bold act.” Davis still hoped that the Lincoln government would understand that the provoked firing on Sumter was a defensive measure, and that an honest attempt at negotiations would occur. Instead of making any attempt to deal with the Confederate government, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteer troops to – using Lincoln’s words – “put down the rebellion.” Davis was disappointed at this clearly unconstitutional action by Lincoln.

Much more could be said about Davis, such as his bravery at the Battle of Buena Vista, the extensive accomplishments and exemplary work he performed when Secretary of War, his great work ethic and attention to duty, his Christian character and acknowledgement of God, his refusal to be pardoned after the war because of his loyalty to the Constitution and what the Confederacy exemplified. Still, I hope this short essay gives you reason to respect this great Mississippian. Instead of being an evil master, he treated his slaves well; instead of being a self-serving politician, he was a statesman with a proper understanding of the Constitution; and instead of being a “fire eater” anxious for war, he hoped it could be prevented and made numerous attempts to communicate and negotiate with the North.

| Tweet |

|

|

|