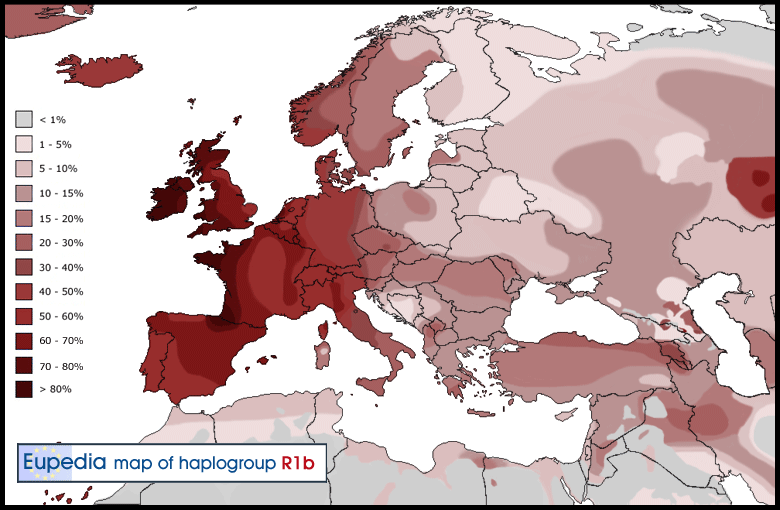

In Part 1 I discussed the differences between Eastern and Western Europe and the cultures behind those expansions. The Y-DNA lineages R1b and R1a can be further subdivided by subsequent mutations in their respective ancestries. In Part II we will take a more in-depth look at the four major subdivisions in Western European R1b, and even connect some of these genetic lineages with populations known in the historical period. All four of these clans descend from a man who carried the R1b mutation labeled L11. The two largest descendants of L11 are the brothers U106 and P312. Together, these two clans represent almost all of the R1b in Europe. P312 is actually the patriarch of another successful three clans that divided later, known as DF27, U152, and L21. To help picture this is a graphic below.

Western R1b Family Tree

We will cover the Bronze Age king or chieftain that was P312 and his three descendants first. His brother, U106, and the path he took are still shrouded in a degree of mystery. P312 and its descendants have almost uniformly been the type of R1b found in the over 100 Bell-Beaker remains that were recently tested in May this year. Jean Manco in her book Blood of the Celts demonstrates that besides DNA, we can archeologically follow a path left by the Bell-Beaker people, particularly from two iconic cultural artifacts. The first artifact is spiraled hair-binders made of precious metals, and the second is stone stelae. Theses stone stelae are anthropomorphic stone monuments, often only the outline of a head and hunched shoulders, but sometimes having a face, hands, and weapons carved into them. These two pieces of evidence stretch from the Pontic Steppe all the way to Western Europe. The first stop was the Carpathian basin in modern-day Hungary, which would have provided ample pasture for the Indo-Europeans’ large herds.

Example of Stone Stelae

DF27: Ibero-Celts

The later trail follows well-known copper ore trade routes that were already established. The Bell-Beakers appear to have been metal workers and traders, and their next stop were the rich copper deposits in the Alps.1 Jean Manco theorizes that the language of these first Bell-Beakers was an early form of Indo-European, not yet differentiated into any specific branch. These early explorers and traders could have brought word back to the Carpathian basin of the rich deposits in Western Europe, resulting in a renewed expansion.

While DF27 moved into Iberia and spread into the British Isles, these Bell-Beakers were probably speaking a Proto-Celtic language, as Celtiberian is the most archaic form of Celtic. This also lends to the idea, preserved in Gaelic oral tradition, that the first Celts in Ireland came from Spain, led by Mil Espaine. DF27 today is found in low levels throughout Europe and has differentiated into different subclades based on geography. The highest concentration of these first conquistadors is in Spain and Portugal, especially amongst the Basques. The fact that this particular clan is so frequent amongst the Basques gives even more credit to its early expansion. The Basques have a language isolate, and perhaps speak the language of the early European farmers that predate the Indo-Europeans. The early carriers of DF27 would have been highly valued members of the pre-Basque population for their metal working knowledge and trade contacts, and spread their Y-DNA, without necessarily changing the language. This is much akin to early traders and trappers in the American West, or even the early Spanish conquistadors in Latin America. Of course, like these more modern examples, these early explorers and traders would have been reinforced by further Indo-European migrations, changing the language and culture of Spain and Portugal. The Basques most likely held onto their own unique heritage by virtue of their mountainous isolation as further waves swept in. While this is one of the smaller of the four R1b clans in Europe, it was spread widely in the New World throughout Latin America.

Modern distribution of DF27 clan

L21: Insular Celts

L21 is the next descendant of the P312 patriarch that we will follow. This branch is most assuredly part of a larger migration, along with its brother U152 into southern Germany. L21 brought the Bronze Age to Britain and Ireland, migrating from its homeland of Central Europe. This is the likely origin of the insular Celtic languages, the only surviving branch of the Celtic language tree. Gaelic is the most archaic of the insular Celtic languages, retaining the K or Q sound rather than what later turned into P on the continent and spread to the Insular Celts of Britain. An example of this can be seen in something as common as “Mac,” meaning “son of” in Q Celtic while it was transformed into “Map,” amongst the Welsh and other P Celtic speakers.2

L21 is particularly strong in the Celtic fringe of the British Isles, and in the province of Brittany in modern-day France, home of the Insular Celtic-speaking Bretons. Over 60% of men from Western Ireland and Scotland are of this clan. Many Americans of Irish, Scots-Irish, and Scottish ancestry paternally are of this Y-DNA haplogroup, making it an extremely large clan for its seemingly small distribution in the old world. Plenty of English carry this Y-DNA line as well, despite becoming culturally and linguistically Germanic via the Anglo-Saxons. Many Celtic men over time would have just adopted the dominant language, and their descendants the dominant culture. Norway and Iceland are also Germanic outliers that carry high amounts of L21. Norwegian Vikings in historical times spread this lineage by taking many Gaelic slaves from Ireland back home to Norway or to Iceland. In Iceland specifically, they now represent 20% of all Y-DNA lineages.

Modern distribution of L21 clan

U152: Italo-Celts

The third descendant of P312 is that of U152, whose progeny were perhaps the most grand in antiquity and could have been considered the superpower of Central Europe. U152 is the lineage associated with the Hallstatt culture, and went on to create both the Italic and the Continental Celtic language families. The Hallstatt cultural period lasted from 1200 B.C.–475 B.C, right to the edge of the Celts’ appearance in written classical sources. The Hallstatt chiefdoms were like the later Celts not centrally organized, but ruled by separate chiefs or kings whose base of power was a fortified hilltop settlement.3 These Celtic chiefdoms mastered iron working around 800 B.C, perhaps from the Cimmerians. This made possible a massive expansion and resulted in major roads being built throughout Central Europe, connecting almost all of Europe with Hallstatt trade routes that made these chiefs extremely wealthy. In fact, these roads formed the basis for the famous Roman road system, the Romans simply bricking over many of the extant Celtic roads.

One of the greater ironies archeogenetics has revealed is that the Italics themselves were most likely derived from the Hallstatt culture, when it expanded past the Alps into central Italy. One theory is that these language families were cut off from each other by the Etruscans, who spoke a non-Indo-European language. This allowed the Italic peoples of central Italy to develop in even further isolation, creating Latin, its most well-known and prolific descendant language, among others. These cousins became the most bitter of enemies in the historical period. The more individualistic and less centrally organized Celts held the upper hand for centuries. One tribe, the Senones, sacked Rome in the fourth century B.C after the Romans had breached international law through their diplomats engaging in warfare against the Celts. These continental Celts expanded far and wide, even into Eastern Europe, where they sacked the Temple of Delphi in Greece. So renowned were they for their fighting prowess that an entire tribe was invited into Turkey to supply mercenaries. This became the Kingdom of Galatia, to whom the Apostle Paul addressed his letter to the Galatians, the first non-Jewish Christian ethnic group.

The Romans absorbed everything their northern cousins had to teach them over time, and waged a much different sort of warfare. To the Celts, warfare had as much to do with honor and personal glory as it did conquering. This element can be seen in the Iliad with the ancient Greek heroes, who strove for personal glory on the battlefield above all else. To the Romans it was a zero-sum game of total warfare that sometimes involved enslaving or putting to the sword entire populations and replacing them with Roman colonies. The Romans, through superior organization, eventually conquered every single continental Celtic kingdom, including even Galatia, resulting in the death of its language and in many ways even its rich culture. U152 today signals that the descendants of this culture spread first by expanding Gallic tribes, and later over the entire Roman Empire by the Romans themselves and the Gauls who served in Rome’s legions. Perhaps this serves as a historical warning to libertarians on the futility of their dogma when confronted with a people who do not play by the same rules.4

Modern distribution of U152 clan

U106: Germanics

R1b U106 I have saved for last, as it is the most removed from the other clans genealogically, and perhaps historically as well. Three theories surround the origin of clan U106, which is most associated today with the West Germanic peoples of Europe. One theory is that it was part of the Battle Axe cultural expansion across northern Europe, and was a minority clan that came with the mostly R1a Indo-Europeans. A second theory is that it was a minority group amongst the Bell-Beaker groups, and broke off early from its fellows heading north. These are both possible, but unsatisfactory in light of what has been discovered: only one U106 individual has been found amongst the Corded Ware culture in Scandinavia, and it was very late in the Corded Ware period. The same goes for the Bell-Beakers: only one U106 individual has been found in the modern Netherlands, and it was very late in the Bell-Beaker period.

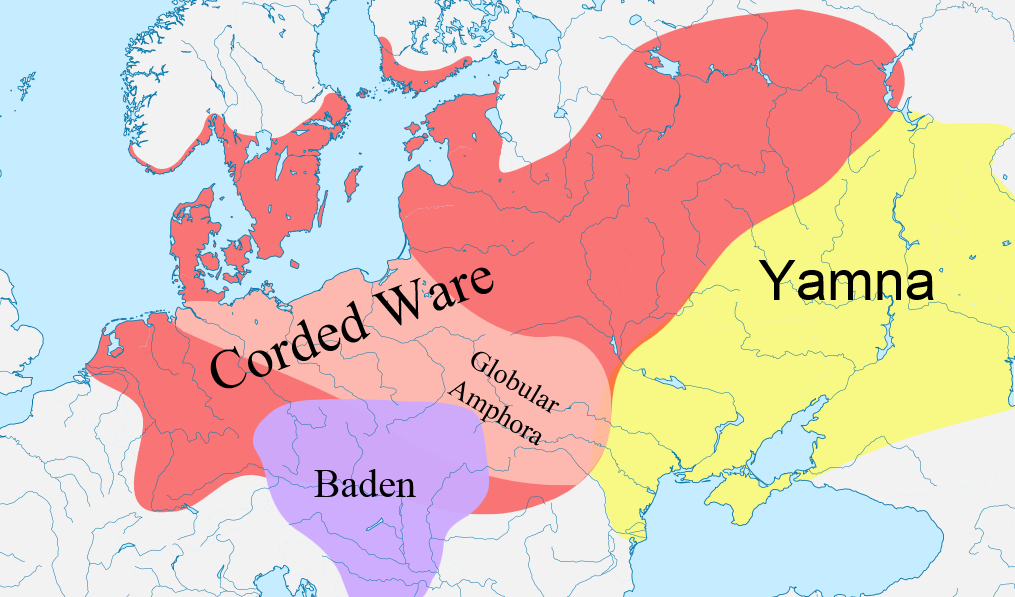

The most plausible theory that I have seen for U106’s earliest origins involve it being one of the early migrations off the Steppe into the Globular Amphora Culture, mingling with an agricultural non-Indo-European speaking people. This is supported by linguistic evidence as well. The Germanic tree is an outlier in regards to other Indo-European languages, with 1/3 of the Proto-Germanic lexicon being non-Indo-European. Most of these words are for agricultural terms, meaning this branch of Indo-Europeans had an early substantive encounter with a non-Indo-European farming culture.5

The Globular Amphora Culture in relation to Corded Ware and Yamnaya Indo-European homeland

This early encounter is perhaps remembered in Germanic oral mythology, later written down in the Christian period as the two different clans of Aesir and Vanir clashing. The Aesir were warlike and represent the Indo-European side of the family, while the Vanir were agricultural and often associated more with fertility and wealth. From this meeting the U106 clan would have traveled north and brought the Nordic Bronze Age to a beginning around 1700 B.C, blending with the previous Corded Ware Indo-Europeans already there. These various blendings are perhaps why the Germanic language tree is so intermediate between the Italo-Celtic and Balto-Slavic superfamilies; it received influence from each of them, as well as from a non-Indo-European language. Modern-day Scandinavians are almost split evenly into thirds by their Y-DNA: 1/3 R1b, which is mostly U106, 1/3 R1a from the earlier Corded Ware invasions, and 1/3 haplogroup I, carried by the Hunter-Gatherers of Scandinavia. U106 came to predominate amongst the tribes that formed the Western Germanic branch.

Of all the clans covered in this article, this is the easiest to connect to historically-known migrations. The Germanic folk wanderings of the 4th-6th centuries A.D. spread the U106 clan to Spain in low levels as the Goths, and to northern Italy as the Lombards. It spread down southern Germany as the Germanic tribes put pressure on the declining Celtic peoples who lived there before. U106 pressed into northern France with the Franks, who bequeathed their name to the modern country and gave us Charles Martel and his even more famous grandson Charlemagne. Perhaps most controversially of all, U106 spread massively into Britain, especially modern-day England, where on the eastern coast it is found at levels as high as 40%. This seems to put to rest both extreme sides of the Anglo-Saxon debate. The Anglo-Saxons did not completely genocide the Celtic peoples who came before, nor were they just a cultural elite of a few hundred that the Celts fancied so much they adopted their language and customs. Today, U106 represents over 25% of all R1b in Europe. Its highest frequency is found amongst the Dutch, and especially the Frisians. Like the Insular Celtic L21 clan, this is a very common Y-DNA clan in North America, brought by the many English, German, Dutch and (to a lesser degree) Scandinavian settlers.

Modern distribution of the U106 clan

For anyone interested in getting their Y-DNA, mtDNA or even both tested, I recommend Family Tree DNA. They have the largest database with an abundance of groups to join and help you learn more about your particular line. It can get much more detailed than the four broad clans I have covered in this essay for R1b. As an important reminder, Y-DNA tells you solely about your direct paternal line. Plenty of Western Europeans have different Y-DNA than the four major clans I have covered today. It does not make them any less Western European in their autosomal DNA than someone with one of these Y-DNA lineages, unless it was from recent admixture. For those of a more practical nature, this is a great genealogical tool, even if you aren’t interested in the more medieval or ancient path your paternal line may have taken. To provide a personal example, one of my surnames has a large group with Family Tree DNA, and their connection to the family of the same name in England was proven through Y-DNA. This is even more helpful for many Southerners, as many paper records were destroyed in the South, and testing Y-DNA can allow people to break through brick walls they have run into on paper.

If anything, I hope this demonstrates clearly our people’s common origin. We truly are extended relatives. While there are real, substantive differences between various Europeans, these pale in comparison to the differences between Europeans and other groups. There are signs that this common spirit can be renewed with the recent showing of solidarity made by various Alt-Right groups in coming to defend Southern monuments in Charlottesville. These men were from many regions of the United States and many different “American Nations.” but all shared a common European origin. No more Brothers’ Wars.

Footnotes

- Jean Manco, Blood of the Celts, ch. 5 ↩

- “Map” was eventually shortened to “Ap.” ↩

- Simon James, The World of the Celts, Chapter 2: “Earliest Celts” ↩

- The cultural difference seen between the Romans and Continentals Celts, who shared the same paternal ancestry, likely involves the differing amounts of Early Farmer ancestry. This difference can be seen even today between Northern and Southern Europeans. Northern Euros put a larger emphasis on individuality and personal liberty and operate on an atomic level with nuclear families. Southern Euros, on the other hand, are more clannish, put more emphasis on extended family (even to the point of living with them), and are more comfortable with a strong central government. ↩

- Jean Manco, Blood of the Celts, Chapter 4: “The Indo-European Family” ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|