The Edict of Thessalonica, issued by three Roman emperors in AD 380, marked the beginning of Christendom.

The persecution of the early Christian Church under the Roman Empire had been temporarily halted for the first time in the early fourth century, with the emperors Constantine the Great and Licinius I, who respectively led the western and eastern parts of the empire, issuing the Edict of Milan in 313. The edict determined that Christians ought to be treated with benevolence within the Roman Empire. Constantine’s successors, Constantius II and Julian the Apostate, favored paganism, Arianism, and Judaism over Christianity, however.

The Constantinian dynasty ended in AD 364, to be succeeded by the Valentinians. The Valentinians would rule the Western Roman empire until 392 and the East until 378. The first two emperors of this dynasty, Valentinian I and Valens, were either impartial towards Christianity or favorable towards the Arians.

In 367 things started to change radically for Christianity in the Roman Empire. Gratian, son of Valentinian I, succeeded Valens as Roman emperor. Gratian refused participation in the imperial cult and removed some pagan idols from public spaces in Rome. He appointed the Christian bishop Ambrose as his chief advisor. He also appointed as Christian co-regent in the East Theodosius I, a cousin of his wife.

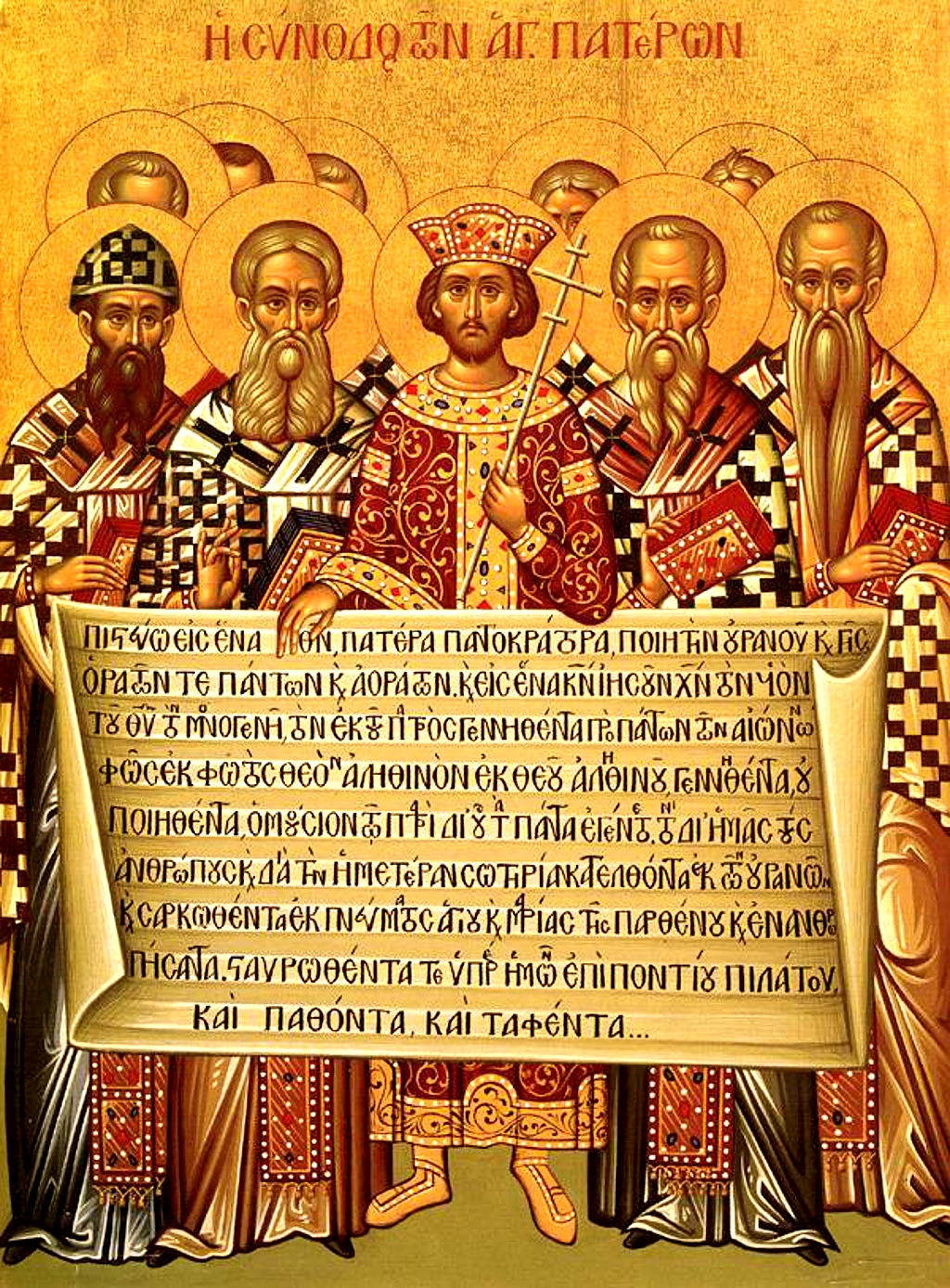

Under the influence of the Church father and bishop Ambrose, Gratian and Theodosius realized that the existing policy of religious pluralism was untenable. With Gratian’s rejection of the imperial cult, a religious vacuum subsisted in the empire, as it had effectively disestablished the public religion of the time. Together with the young western co-regent, Valentinian II, they consequently issued the Edict of Thessalonica, which officially made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire.

The edict stated:

It is our desire that all the various nations which are subject to our Clemency and Moderation, should continue to profess that religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by faithful tradition, and which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic holiness. According to the apostolic teaching and the doctrine of the Gospel, let us believe in the one deity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. We authorize the followers of this law to assume the title of Catholic Christians; but as for the others, since, in our judgment they are foolish madmen, we decree that they shall be branded with the ignominious name of heretics, and shall not presume to give to their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of the divine condemnation and in the second the punishment of our authority which in accordance with the will of Heaven we shall decide to inflict.

The edict is also known as Cunctus populos, the first two Latin words of the edict often translated as “various nations”, but could be even better translated as “conjoining nations”. The first two words chosen by the Christian Emperors speak volumes about their view of and vision for the empire. The emperors did not view the empire as a country. They did not view it as a nation. They viewed it as a group of Christian nations peacefully co-existing under their reign. In other words, they rejected the idea of propositional nationhood. This indicates a clear understanding of the Christian worldview principle of the one and the many, rooted in God’s trinitarian nature, on the part of these two great emperors.

Calvinist philosopher R.J. Rushdoony noted:

The religious reduction of all reality to one is pantheism. . . . [It] presupposes unity as the one virtue. . . . [In contradistinction] we have a distinction which does not exist in non-Christian thought: we have a temporal one-and-many in the created universe, and we have an eternal One-and-Many in the ontological trinity.1

This was the philosophy of the emperors. It is very different from the unitarian aims of Enlightenment-inspired organizations like the United Nations, which tolerate none of God’s creational distinctions. In fact, the Christian civilization that this edict initiated was characterized by a plurality of co-existing governmental authorities exercising decentralized power in a fashion that can best be described as subsidiarity: dukes, princes, bishops, kings, and emperors all co-reigned peacefully in Christendom for more than a thousand years. This established arrangement would only be interrupted by the amalgamationist objectives of the French Revolution, which marked the beginning of the end for Western Christendom.

I chose this particular aspect of this historic edict as my focus for this article, but other commendable elements clearly expressed in the edict that cannot go unmentioned include the respect for tradition as the means of preserving true religion, and the solidly theonomic view of law.

The Edict of Thessalonica needs to be re-affirmed once we, as white Christian nations, regain self-determination.

Footnotes

- RJ Rushdoony, The One and the Many. Thoburn Press: Fairfax, Virginia, 1978, pp. 6, 7,10 ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|