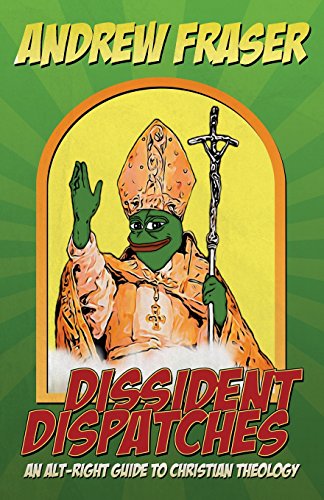

I confess, I didn’t expect much from this book. On sight, the cover image of Pepe the Frog as pope announces this as a work of satire, no doubt riddled with irreverence and blasphemies.

But I was pleasantly surprised. Fraser is a serious thinker, cover notwithstanding.

An accomplished attorney, Andrew Fraser saw the eclipse of Christian law and civics, and White nations with them, as nearly a fait accompli. But he rightly perceived these abdications and usurpations to be borne on a wind beyond policy: a spiritual tide, and therefore, a matter of theology.

So he set out for seminary late in life, hoping to take the wall where the fight for the traditional world order still raged hot. But rather than an entrenched church contra mundum, he found just the opposite — the watchmen of objective meaning and morality were nowhere to be found. Those who now occupied their posts proved indistinguishable from the Humanists assailing Christendom and the White race without. He found the siege on the Church and European civilization in as much as out. Or in his words, “The differences between mainstream Christianity and the cultural Marxism common to most academic disciplines is difficult to discern.” Because those institutions are now defined by a “nasty anti-white animus prevalent among the disingenuous white liberals and non-white racial activists who dominate contemporary theological discourse.” (p. xiii)

So much so that his tenure as a student was defined by continual harassment and threats of expulsion for merely speaking and writing candidly on certain topics in the voice of traditional Protestantism. This book is the ensemble of academic essays and notes which came of that tenure.

The book opens in consideration of no small subject — the modern revolution in exegesis. (pp. 2-7) Which Fraser attributes directly to the messianic prophecies of the OT proving of special insult to the Jews. The example he leads with on this subject is how radically different the interpretation of Psalm 22 was among the Patristic and Reformation fathers in comparison to modern interpreters. All traditionally understood the “dogs” of “the congregation of the wicked” who “enclosed” the Messiah to be (in the words of Eusebius) ‘the rulers of the Jews, the Scribes, and High Priests, and the Pharisees who spurred the whole multitude to demand His blood against themselves and their own children’, consonant with “the synagogue of Satan” referenced in Revelation. Obvious as that is, modern exegetes typically shun both the perspicuous meaning and those who dare endorse it.

The Jews, of course, declaim any such reading as ‘antisemitism.’ No surprise there, but the majority claiming Christ today turning to side with the Jews against Christ does rock us on our heels. Yes, the ascendant view of Psalm 22 even in Christian seminaries is now as a description of David’s unique suffering universalized. Odd as that is, taking the ‘congregation of the wicked’ as “all oppressors” (i.e., White males) is considered obligatory. And if said text is allowed to pertain to Christ at all, it is only in the secondary and universalized sense, as synecdoche for all ‘oppressed’ (i.e. non-Whites).

This de-christening of messianic passages, and the weirdling exegetical approach on which it relies, Fraser frankly attributes to “fear of the Jews.” Nothing more or less. And with respect to OT messianic prophecies, this is difficult to deny. Because those who make the case for such a hermeneutic typically employ the via negativa, warding all away from the traditional view because “it leads to the gas chambers.”

So Judaized, it begs the question of how claimants of Christ who consent to this approach to prophecy and typology might be considered Christian in any meaningful way. If bowing to the PC zeitgeist and the pride of the Jews over Christ to the degree that they will mute or deny the prophecies of Messiah, they simply serve another god.

In chapter 3 he identifies Barth’s ‘hermeneutics from below’ on which he justified his self-professed communism and war against historic Christendom as an overt rejection of divine revelation, and Christianity with it. Supersessionism, as well as the traditional conceptions of family, race, and gender, were all born of the ‘hermeneutics from above’ and a view of Scripture as plenary revelation. To be an inerrantist is to be a patriarchal antisemite and racist by default.

He briefly deconstructs one New Age hero after another: he refutes Bonhoeffer by doing no more than relaying the man’s position: “Only one nation can claim to have been ‘the hidden centre of history, put there by God.’ For Bonhoeffer, ‘Israel stands alone’ as the ‘place where God fulfills His promise.'” (p. 18)

He had a higher view of antichrist Jews than the Church comprised of Christian nations — a position obviously foreign to Scripture. Prior to consideration of his other heresies, this alone identifies him as an extreme Judaizer, and apostate.

But in an ecclesiastic atmosphere where Bonhoeffer is regarded a giant of the faith, Fraser’s critique is itself deemed heresy.

He deals alternately with feminist and liberation theologians. The former holding masculinity the definition of evil, and women’s only sin insufficient aggression against it; the latter holding Whiteness to be the definition of evil, and dark people’s only sin insufficient aggression against it. The overlap of which — militancy contra White Patriarchy — perfectly defines the prevailing secular ethos. No inkling of contra mundum thought, there. The supposed clergy are now in total lockstep with the church’s most aggressive enemies.

Fraser rebukes the narrative of men like J. Kameron Carter who teach that all non-White peoples share a special communion through the priestly office of the Jews, and in them, God (p. 25). In Carter’s words, ‘Israel is already a mulatto people precisely in being YHWH’s people’ and ‘Jesus himself as the Israel of God is mulatto.’ (p. 26) From which Carter further confers to all non-Whites a similitude, bordering on total equivalence, with deity.

And the consequence of Carter’s deification of Blackness, miscegenation, is recognized no less in his exaltation of all African social dysfunction. (p. 27) If dark skin is divine, then the copious savagery committed by dusky hands is deemed holy.

One recurrent theme somewhat unexpected is that his professors took major exception to Fraser’s preterism. Not so much for the position itself, as on account of its implications of Supersessionism. Because it is, according to Jews, the zenith of antisemitism. And this is not his own guessing at the motives therein, it’s the result of his adversaries making their case on said premises. It truly does appear that our churchmen have popularly abandoned an inaugural view of the Kingdom in preterism specifically because its Supersessionist implications are an affront to the Jews.

Along related lines, Fraser relays a brilliant exchange between himself and one Dr. Havea (p. 53): the professor was lecturing on how the biblical account of Joshua bringing down the walls of Jericho should not be trusted because we have no forensic proof of it. To which Fraser replied by basically asking the professor why he was denying the holocaust*.

Of course, he was trolling the professor, but it was more than that. He was crystallizing the fact that Havea had greater faith in the testimony (and fear) of Jews hostile to Christ than in the testimony of God Himself!

In which case, he had reduced not only Havea’s textual criticism to absurdity, but his office, and his claim to be a Christian as well, to utter obscenity.

This exchange fatally undercut not just Dr. Havea, but the whole institution, and the whole edifice of the modern church which has been erected on such premises contrary to God’s Word.

He tackles even subtleties in ecclesiology that people expect to be insulated from the liberal taint; but Fraser sniffs out all the defeatism and Radical Two Kingdoms dreck, as well as the radical Liberationist, postmodernist, and Marxist themes prevalent there.

Over against the Protestant Reformation, he identifies the thought of Karl Barth as seminal to the Protestant Deformation — a radical break with the Reformed doctrine of nations. He therein takes the intersection of communism and philo-Semitism in Barth’s so-called Neo-Orthodoxy as a relativism not only in the theory of revelation, but necessarily in the nature of man also:

According to Barth, ‘the concept of one’s own people is not a fixed, but a fluid concept’. Such ideas have become the conventional wisdom of our time. Similarly, few theologians today demur from Barth’s claim that ‘the majority of peoples have for centuries been physical mongrels’. Mainstream Christians in every erstwhile Anglo-Saxon country now ‘confess our people as a historical construct,’ their purely contingent national identity cannot be identified as a command of God or a presupposition of the divine order of things.In his struggle to overturn the orthodox Christian doctrine of nations, Barth’s ideological triumph was complete. But that victory exacted a steep price. (pp. 78-79) …

The key to understanding the Protestant deformation of Christian nationhood lies in Barth’s futurist eschatology … Barth’s highly refined brand of millennialism contributed to a broader ecumenical movement that led liberal Protestants to embrace mass Third World immigration while pointing conservative evangelicals, especially in the USA, toward Christian Zionism. (p. 83)

Whereas this trend was already afoot in Evangelical circles by way of Scofield’s dispensationalism, Barth successfully planted a similar seed in Reformed circles.

Fraser also takes pains to critique the xenophilia common now in all quarters of Christendom. This he terms ‘the Cult of the Other’ which has taken over the Uniting Church of Australia; but his commentary on the subject is pertinent to all extant denominational settings. Any and all besides White males are esteemed of more innate worth and are therefore socially promoted to the bully pulpit in all such environs. Their word, their interpretations, their critiques, their feelings — everything — is counted of higher value if from the Other.

I certainly and emphatically do disagree with his assessment of America’s founding and our institutions, but they are nothing dissimilar from the sort of critiques common now in leftist academia. So in spite of Mr. Fraser’s many other wonderful insights, I take a pass with respect to his discussion of the Constitution and our founding faith.

That said, however, his thoughts on contemporary America are quite solid. Colorblind Tea Party-type Republicanism is dead in its trespasses as it repudiates the exclusiveness of both our founding faith and folk in deference to the other, be they Blacks or Israeli nationals. A conservatism that conserves nothing of import.

He even waxes long on surprising nuances of American politics, such as the dire significance and portents of the Obama presidency, the merit of the Birther movement, and the futility of Whites making appeals to law and order in the face of naked identity politics brought to bear against us by all the aggrieved antipodes of the earth.

But being a WASP Anglican, he is an ardent Anglophile and takes the Loyalist/Royalist side of the American War of Independence. So his answer to our civic woes lies in a reprisal of the British monarchy and a restored commonwealth.

Not only is that a ship long since sailed historically, our ancestors disembarked it for thoroughly biblical reasons, and the extant royal family is beneath contempt for their wholesale turn against both Christ and our folk.

Nonetheless, I must applaud his tackling subjects like “the Trinitarian theology of Christian Nationhood” and the concept of a perspectival Volksgeist. This is an excellent statement:

By the end of the first millennium of the Christian era, Spirit, water, and blood were the constituent elements of every Christian nation. Those three-dimensions of Christian racial/ethnic identity reflect the unity in diversity of the three persons of the triune God. (p. 173) …

Race-as-theology helps us to understand how Spirit and blood mingled with the life-giving pour of water to sustain the first, embryonic Christian communities. Since then, Christian nationhood has been nourished by the continuing interplay of Spirit, water, and blood. (p. 174)

He even elaborates many providentially arranged forerunners to Trinitarian theology in the many triadic concepts woven throughout the societies of pre-Christian Europe. This is a topic in sore need of greater study and explication.

However, in spite of his early defenses of plenary hermeneutics and Protestant methodology, he does take a turn contra these things in his segment titled Theology: Queen of Racial Science? Therein he argues that because “Darwinian biology and modern geology undermine literalist interpretations of the creation . . . Christians are under no obligation to affirm that Adam was created ex nihilo as the first man in a physical Garden of Eden somewhere in the near East.” (p. 181)

Whence he espouses the thoroughly liberal notion that “Adam is best understood as a metonym for Old Israel.” (p. 182) And secondarily, a lens through which each Christianized race may analogize their own nativity.

All of which he turns to, by his own admission, to ground a theology of race. But I submit that for all his creativity, he has simply missed the historical and orthodox theology of race that is, in fact, consistent with creationism. And casting about in desperation, he has done here the very thing he abjures in his liberal adversaries.

But this does not seem to hinder him, thankfully, in perceiving the errors of the same methodology in the thought of N.T. Wright, James Dunn, or Karl Barth.

In Conclusion:

By virtue of the fact that Dissident Dispatches is a compendium of position papers and academic correspondence with respect to the same, it forms a small library in itself. This puts it beyond the reach of any comprehensive review, because to treat all his arguments as they deserve, one would have to write a work of comparable size to the one under consideration. So the best that can be done here is an overview of the man’s thought.

His principal emphases are Supersessionism, preterism, the Trinitarian organization of the world and society, redress of textual criticism as predicated on ‘fear of the Jews,’ rebuke of the ‘Cult of the Other’ forming an anti-White social hierarchy trending toward genocide of the White race in full, and a hope for spiritual and geopolitical reorientation of the Anglo-Saxon Volkgeist under a restored monarchy.

While I disagree with that last thesis, and many lesser particulars besides, it is apparent that Dr. Fraser has made some significant contributions here. Not least of which is that in his critiques of Wright, Dunn, Bultmann, and Barth, and the whole modern seminary and denominational system, he does not hesitate to pronounce our churchmen “post-Christians” on the grounds that the majority are feminists, liberationists, deconstructionists, Judaizers, Gnostics, and heretics of every sort. If we dare look at the situation as it really is, it is an open and shut case. And if we hope to see dawn break over this darkness, we must start speaking to the issue as such. Islands of resistance notwithstanding, Christendom is apostate today.

At the end of the day, Fraser identifies the problems that have brought on the collapse of Western civilization and the destruction of the White race as not foremost a matter of geopolitics, or economics, or any externalities: these are all symptoms, not the ailment. Rather, he identifies the problem as our fathers did — in our people’s own infidelity to the covenant; an infidelity introduced not in plebiscites or statecraft, but more essentially in the liberalized interpretation of Scripture and an anthropocentric methodology. Which is to say, rebellion against the Word of the Lord. And that, for no more complex a motive than ‘fear of the Jews.’

Here is the conclusion of the matter:

Liberation theologians are, therefore, eager to ‘exorcise’ any ‘scriptural text’ that adds support, inter alia, to slavery, supersessionism, and traditional Christian understandings of the sexual division of labour. As a consequence, liberation theology seems to have entrenched a new-modelled theology of dominion set in opposition to the foundational authority of the Bible — the dominion of the politically correct in a post-Christian society ever-ready ‘to adopt a hermeneutic of generosity toward our religious other.’ In these circumstances, orthodox Christians can only pray for the postmodern rebirth of communities of faith in which the Bible becomes the charter of a reformed theology of dominion. (p. 15)

The dilemma of White dispossesion and genocide, at root, is a spiritual problem: the loss of a truly received revelation from God, His establishment of the nations, and the Volksgeist of each under His sovereign dominion.

No political wrangling will save the White race. No bootstrap Nietzchean will-to-power will preserve us. The panacea for the perishing WASP and world Eury in diaspora is our return to the gospel of Jesus Christ and the subsequent application of His Law-Word to all areas of life, for “by your faith, you are healed.” (Mk. 5:34)

| Tweet |

|

|

|