Three years ago, I posted a quote from an Eastern Orthodox official postulating that the real divide in Christendom is increasingly between liberals and traditionalists rather than between the individual branches of the Faith.

All current versions of Christianity can be very conditionally divided into two major groups – traditional and liberal. The abyss that exists today divides not so much the Orthodox from the Catholics or the Catholics from the Protestants as it does the ‘traditionalists’ from the ‘liberals’.

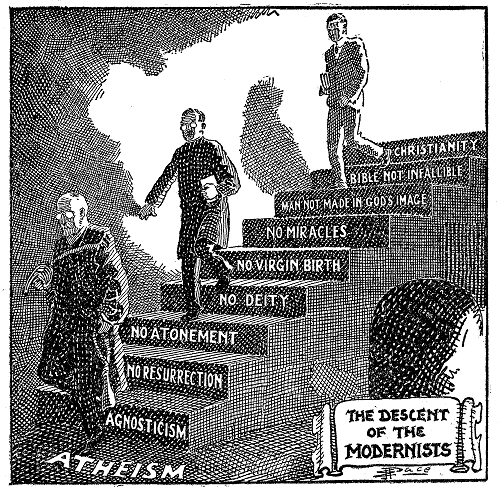

Indeed, the path I’ve taken on Faith and Heritage can be roughly generalized as something of a synthesis of Reformed Protestant theology, traditional Catholic economic and social teachings, and Eastern Orthodox views on church and nation. This is in no way to belittle the very real and important theological differences between those branches, but at least the traditionalists have a common basis on which to debate their differences. How does one have a conversation with liberal “christians” who celebrate homosexuality, abortion, the police state, radical feminism, Marxist egalitarianism, and other degeneracy while disbelieving in the literal, infallible truth of Scripture, heaven and hell, the resurrection, the virgin birth, the Trinity, and other Christian essentials, other than to denounce their views as sinful and call them to repentance and salvation?

In fact, liberal “christianity” has been so stripped of actual Christianity that most of its adherents don’t even bother going to church anymore.

Traditional believers, both Protestant and Catholic, have not necessarily thrived in this environment. . . . But if conservative Christianity has often been compromised, liberal Christianity has simply collapsed. Practically every denomination — Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian — that has tried to adapt itself to contemporary liberal values has seen an Episcopal-style plunge in church attendance. Within the Catholic Church, too, the most progressive-minded religious orders have often failed to generate the vocations necessary to sustain themselves.

But though these liberals have rejected the substance and often even the label of Christianity, they haven’t rejected the concepts of sin and salvation or the messianic fervor to spread this salvation. Just as the Unitarian abolitionists of the nineteenth century, though rejecting their Puritan grandfathers’ Christianity, still preached salvation through their crusade to abolish the Christian institution of slavery, so too the atheist, agnostic, and liberal grandchildren of the early-twentieth-century social reformers still preach salvation, but through the liberal social gospel stripped of true Christianity, even when retaining some of the trappings and terminology.

Joseph Bottum in his new book, An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America, proposes that liberalism and the liberal elite in America have a religious, rather than social, basis.

Bottum’s thesis is that there really isn’t a new American caste. This “class” that has outsize influence on America’s moral and spiritual life is roughly the same class that has always had it: Mainline Protestants, only now without the doctrinal Protestantism or the churchgoing. . . .

In Bottum’s revisionist account, Protestant preacher Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918) looms as the figure who most succinctly defined the spiritual mission of 20th-century Mainline Protestantism and its heirs. He put “social sins” at the front of the Mainline imagination. “The six social sins, Rauschenbusch announced, were bigotry, the arrogance of power, the corruption of justice for personal ends, the madness of the mob, militarism, and class contempt,” Bottum writes. . . .

Not all of Bottum’s post-Protestants are directly descended from Mainline members. Jews, Catholics, and even atheists join this unofficial spiritual-but-not-religious tribe, just as before many Jews, Catholics, and nonbelievers joined Mainline churches as a way to signal their arrival in a new, important social class. . . .

For Bottum, what is remarkable is the way the spiritual experience of Rauschenbusch’s “social gospel” is so like the experience of modern liberalism. According to Rauschenbusch, one opposes these social sins through direct action, legislative amelioration, and simply recognizing their effect and sympathizing with their victims. Rauschenbusch wrote, “An experience of religion through the medium of solidaristic social feeling is an experience of unusually high ethical quality, akin to that of the prophets of the Bible.”

The post-Protestants Bottum identifies have just that, “a social gospel, without the gospel. For all of them, the sole proof of redemption is the holding of a proper sense of social ills. The only available confidence about their salvation, as something superadded to experience, is the self-esteem that comes with feeling they oppose the social evils of bigotry and power and the groupthink of the mob.”

With the proper feeling comes a proper sense of guilt, and a missionary’s zeal to correct wrongs. Over a century ago Rauschenbusch wrote, “If a man has drawn any religious feeling from Christ, his participation in the systematized oppression of civilization will, at least at times, seem an intolerable burden and guilt.” Bottum deftly notes that in theological terms this signals “a nearly complete transfer of Christian fear and Christian assurance into a sensibility of the need for reform, a mysticism of the social order — the anxiety about salvation resolved by ecstatic transport into the feeling of social solidarity.”

Can we not hear in the progressive’s soul-searching examination of his own “privilege,” as well as his unconscious participation in structural injustice, an echo of Rauschenbusch’s words? Whereas Catholics make an examination of conscience before confession, and confess their personal sins before promising to amend their life, today’s progressives examine their place in the social structure of oppression, and then vow to reform society. That is what it means to have a “social gospel without the gospel” — to be motivated by religious impulses, but believe it is entirely secular.

The social gospel is not the Christian Gospel which has been made abundantly clear in modern American society. This is why the divide is taking place between traditionalists and liberals, not really because the traditionalists in the different branches are moving closer together, but because the liberals are no longer members of the same religion.

| Tweet |

|

|

|