THE FIRST WORD

THE SECOND WORD

THE THIRD WORD

THE FOURTH WORD

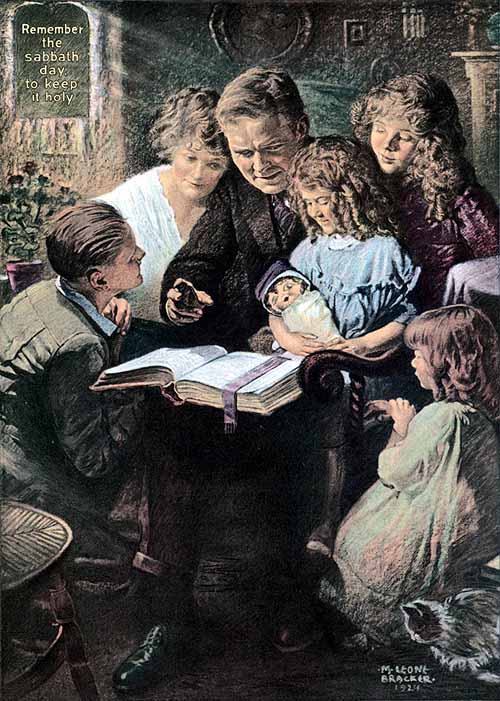

Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Six days shalt thou labor, and do all thy work:

But the seventh day is the sabbath of the Lord thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor thy maidservant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates:

For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it.

The fourth law is addressed to the federal heads of household, and thereby presupposes a more limited context of authority inside the national body – that of clan and house. It is to this federal-familial authority structure that the sabbath is most immediately entrusted, albeit inside the national framework.

It refutes the equalitarian myth promulgated in the churches today that there is no separation nor distinction between covenant families. For it charges the federal head of every house foremost with domestic responsibility over his own clan, not his neighbor’s. This was the onus of limited responsibility expressed by Joshua: “but as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord” (Josh. 24:15). This same priority of close kin is emphasized by Paul – that a man should “provide for his own, and specially for those of his own house” (1 Tim. 5:8). In place of the term ‘his own’ (Grk. idion) which has in recent years become an archaic idiom, many modern translations have, for clarity’s sake, opted for the word ‘relatives,’ which communicates the idea well enough. But Matthew Poole is emphatic: “By his own he means his relations, all of a man’s family or stock.”1 ‘Stock,’ of course, being a preferred synonym for ‘race.’

If this principle were not clear enough, Isaiah dispels all question of intent, saying, “hide not thyself from thine own flesh” (Isa. 58:7), which, in context, clearly signifies one’s provision for one’s blood relations. Augustine’s commentary on this passage doubly affirms that Moses, Joshua, Paul, and Isaiah had the same principle in view:

For the examination of a number of texts has often thrown light upon some of the more obscure passages; for example, in that passage of the prophet Isaiah, one translator reads: “And do not despise the domestics of thy seed;” another reads: “And do not despise thine own flesh.” Each of these in turn confirms the other. For the one is explained by the other; because “flesh” may be taken in its literal sense, so that a man may understand that he is admonished not to despise his own body; and “the domestics of thy seed” may be understood figuratively of Christians, because they are spiritually born of the same seed as ourselves, namely, the Word. When now the meaning of the two translators is compared, a more likely sense of the words suggests itself, viz., that the command is not to despise our kinsmen, because when one brings the expression ‘domestics of thy seed’ into relation with ‘flesh,’ kinsmen most naturally occurs to one’s mind.2

The onus of responsibility in biblical law, therefore, prioritizes kinship, first with respect to immediate family, and then, proceeding outward by concentric circles, to tribe, ethnicity, race, and at length, men generically.

Albert Barnes’s commentary expounds on this subject with chilling poignancy:

The words “his own,” refer to those who are naturally dependent on him, whether living in his own immediate family or not. There may be many distant relatives naturally dependent on our aid, besides those who live in our own house.

And specially for those of his own house – Margin, “kindred.” The word “house,” or “household,” better expresses the sense than the word “kindred.” The meaning is, those who live in his own family. They would naturally have higher claims on him than those who did not. They would commonly be his nearer relatives, and the fact, from whatever cause, that they constituted his own family, would lay the foundation for a strong claim upon him. He who neglected his own immediate family would be more guilty than he who neglected a more remote relative.

He hath denied the faith – By his conduct, perhaps, not openly. He may be still a professor of religion and do this; but he will show that he is imbued with none of the spirit of religion, and is a stranger to its real nature. The meaning is, that he would, by such an act, have practically renounced Christianity, since it enjoins this duty on all.3

As orthodox Christians we take Paul’s prioritization of kinship as harmonious with, and indeed founded upon, the law itself. So we see just how serious a matter lies before us, for those who refuse to accept the ethical priority established by God of kinship would seem to be rejecting not only the fifth law, but God’s covenant of which it is such an integral part. We are therefore warned that egalitarianism is a forfeiture of the Christian faith. In regards of our modern egalitarian world, this should make our blood run cold.

The severity of this principle was likewise underscored by the Church fathers such as Tertullian:

Do we believe it lawful for a human oath to be superadded to one divine, for a man to come under promise to another master after Christ, and to abjure father, mother, and all nearest kinsfolk, whom even the law has commanded us to honour and love next to God Himself, to whom the gospel, too, holding them only of less account than Christ, has in like manner rendered honour?4

Though viewed as scandalous amongst the churches in recent decades, the priority of kinship was always understood of Christendom past as penultimate beside devotion to God, and, as Tertullian intimated, entwined inextricably with the Gospel itself. Yes, prior to the last few decades, Bengel’s maxim was the patent summary of the Christian view: “Faith does not set aside natural duties, but perfects and strengthens them.”5

None of which is to discount or dismiss the onus we have toward Christians of all breeds. In deed, they are near relation as it pertains to the household of faith (Gal. 6:10), but that household is made intelligible only by its countervailing analogy, which is the kin-based household (1 Tim. 5:8) established in law as the undergirding social order of covenant Christianity. Apart from the Kinist understanding here, not only do we forfeit exclusive claims to our own physical wives and children, but we also lose the God-ordained analogy by which spiritual relations are made intelligible. And directly refuting the Alienist claim, we know the law forbids confusion of anything that is our neighbor’s for ours (Ex. 20:17).

The fourth law also affirms the propriety of domestic slavery. No amount of wrangling will undo it. This principle is further subdivided into various codes particular to their own circumstances: some address hirelings, native as well as stranger (e.g. Deut. 24:14-15; Lev. 19:13; 25:39-40; Jer. 22:13), others, a seven-year limited term of servitude for men of one’s own race (e.g. Ex. 21:2; Deut. 15:2-3), and others still grant the option of perpetually retaining slaves only in the case of foreign races (Lev. 25:44-46). Slaves and masters are elsewhere addressed generally (e.g. Ex. 21:20-21; Col. 4:1; Eph. 6:9).

44 Both thy bondmen, and thy bondmaids, which thou shalt have, shall be of the heathen that are round about you; of them shall ye buy bondmen and bondmaids.

45 Moreover of the children of the strangers that do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy, and of their families that are with you, which they begat in your land: and they shall be your possession.

46 And ye shall take them as an inheritance for your children after you, to inherit them for a possession; they shall be your bondmen for ever: but over your brethren the children of Israel, ye shall not rule one over another with rigour.

(Leviticus 25:44-46)

While modern churchmen are overjoyed to draw upon Leviticus 25 for reference to the fifty-year sabbath of Jubilee insofar as they can portray it as wealth redistribution and proto-socialism, few now countenance the weekly sabbath which undergirds it. Virtually none dare interact with the above section which sanctions (in at least some instances) the perpetual slavery of foreigners. Moreover, moderns are loath to admit that since the explication of the fifty-year sabbath has slave codes woven into it, it confirms that the fourth law’s reference to manservants and maidservants in Exodus 20:8-11 truly does intend domestic servitude as normative to sabbath law. Treating the Jubilee as an aspect of the sabbath, Rushdoony tells us:

The essence of the sabbath is the work of restoration, God’s new creation; the goal of the sabbath is the second creation rest of God. Man is required to rest and to allow earth and animals to rest, that God’s restoration may work, and creation be revitalized. Every sabbath rest points to the new creation, the regeneration and restoration of all things.6

If the sabbath as a day of recreation is literally ‘re-creation’ exemplifying the redeemed social order, it is presented in the Fourth Word and Jubilee principle as an inherently stratified, hierarchical, familialist, nationalist, paternalist, and – in the language of cultural Marxism – ‘racist’ order.

The Jubilee return of all lands, leased or sublet, to the Israelite tribes and families to which they were originally apportioned exemplifies ethnic protectionism, ensuring that no Israelite line could be divested or uprooted either by kindred tribes or foreign nationals. Yes, the bloodlines of Israel were thus rooted to the land inalienably. Foreigners, though able to lease, had no right of allodial claim to the land. Sabbath law forthrightly mandates what are regarded as the most odious principles to post-WWII sensibilities – blood and soil.

As the winds of zeitgeist move through the Church, this unavoidable national-familial framework of ordered hierarchy in the covenant is not refuted, but simply ignored or shunned. The only recourse left to our humanist-programmed brethren is some form of utopianism.

Man is reduced to economic man and viewed in terms of an externalism which destroys man. Utopianism not only presents an illusory or dangerous picture of the future, but it also distorts and destroys the present. Utopianism thus affords man no help as he works toward the future: it gives man illusions which beget only needless sacrifice and work and produce nothing but social chaos.7

But the last category to be addressed in the fourth law under the authority of the householder is ‘the stranger within thy gates.’ We cannot miss that in the words of the catechism, strangers abided ‘under the charge’ of an Israelite house.8 The law places the stranger and his labor directly under the paternal oversight of the domestic authority – the bayith, the clan. Far from blurring the stranger’s standing as a stranger, declaring him indistinguishable from an Israelite, or as an ‘honorary’ or ‘naturalized’ Israelite, the law insists upon his abiding distinction as a stranger. To eisegetically impose egalitarianism here, as if the stranger within one’s gates was not to be regarded as that which the law calls him, is not only a hermeneutical error, and violence to the text, but nullification of the law. As obvious a fact as it is, we are compelled to underscore the point, that if the sabbath law speaks to the stranger as a category under authority to an Israelite family, then strangers exist. Even if bonded to a native’s house, they abide as distinguished from said house. To claim belief in the sabbath, while denying that strangers differ at all from blood-natives, or while rejecting the ethnic paternalism presupposed in this law, is to argue that we should not allow the law to mean what it plainly says.

No, we see that the stranger sojourning under conditions of theonomy had legal standing only under the patronage of a native clan:

15 So I took the chief of your tribes, wise men, and known, and made them heads over you, captains over thousands, and captains over hundreds, and captains over fifties, and captains over tens, and officers among your tribes.

16 And I charged your judges at that time, saying, Hear the causes between your brethren, and judge righteously between every man and his brother, and the stranger that is with him.

(Deuteronomy 1:15-16)

The stranger’s standing, then, in matters juridical was, as with matters labor-oriented, contingent upon his being ‘with’ an Israelite. Whether a merchant, laborer, or ambassador, the stranger’s ‘resident alien’ status was held valid only under the bonded surety of an Israelite benefactor: this was indemnity to “‘the stranger,’ who according to the law could have a legal claim to no land in Israel,”9 and would otherwise be left without the needful means of navigating what to him was a foreign polity and culture. This is what it means to ‘love’ the alien: to fulfill the law toward him. Aside from doing him no wrong, this is what it means to ‘treat the alien as one born among you’: legal representation by suretyship lending him the proxy of an Israelite’s standing in court. Whatever legal entanglements come to the stranger, they did so only under the supervisory liability of his Israelite sponsor.

We now know by contemporary experience just how wise the law is in this respect, as the alternative – egalitarianism for the stranger in our lands – leaves the alien lost in an unfamiliar society, unaccountable in the land, and incentivized toward criminal predation upon the native populace. Absent the law’s paternalism and protectionism, the stranger is a subversive element, hostile toward, rather than thankful for, the nation hosting him.

All of which Solomon took into the scope of his counsel, advising his son that the patron of a stranger, so contracted, must walk circumspectly and take precaution to well indemnify himself:

1 My son, if thou be surety for thy friend, if thou hast stricken thy hand with a stranger,

2 Thou art snared with the words of thy mouth, thou art taken with the words of thy mouth.

(Proverbs 6:1-2)

Clark therefore summed up the stranger’s status thus:

And in Mosaic law, it was not deemed improper to exclude strangers from participating in religious affairs, to exempt them from the benefits of the seven-year release, to give or sell them meat of animals dying of themselves, nor upon occasion to segregate and enumerate them. Thus “David commanded to gather together the strangers that were in the land of Israel” [1 Chron. 22:2], and Solomon “numbered” all the strangers that were in the land [2 Chron. 2:17].

Though the law required that strangers be fairly treated, it was not intended that they should “devour” the land [Isa. 1:7] or the strength of the people [Hos. 7:9], nor that they should fill themselves with the wealth of the people through exploitation [Prov. 5:10]. On the contrary, it was evidently supposed that the strangers, with some exceptions, should constitute a subservient class, from whose ranks bondmen and hired servants might be obtained. . . . In Isaiah it is said that “strangers shall stand and feed your flocks, . . . the sons of the alien shall be your plowmen and your vine-dressers” [Isa. 61:5], and “the sons of the strangers shall build up thy walls.” Solomon, in building the “house of the Lord” and the “house for his kingdom,” set the strangers apart, some to be bearers of burdens, others to be hewers in the mountain, and others to be overseers [2 Chron. 2:17, 18].10

As if to dispel any illusions that these strictures are in any way arbitrary, all matters social, labor-oriented, and litigious are in the sabbath law conceived as being anchored in the elements and divisions of creation itself. If ‘thy stranger that is within thy gates’ is constrained under the authority of an Israelite family to observe the sabbath on the grounds that ‘in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it’ (Ex. 20:11), then this enduring distinction between Israelite and stranger is, upon the Creator’s authority, concession to and maintenance of complementarity in the created order. Nations violate it only at their own peril.

THE FIFTH WORD

Footnotes

- Matthew Poole’s commentary on 1 Timothy 5 ↩

- Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, book 2, chapter 12 ↩

- Albert Barnes’s commentary on 1 Timothy 5 ↩

- Tertullian, “The Chaplet, or De Corona,” chapter 11 ↩

- Johann Albrecht Bengel, Gnomon of the New Testament, 1 Timothy 5 ↩

- R.J. Rushdoony, The Institutes of Biblical Law, p. 143 ↩

- Ibid., p. 158 ↩

- Westminster Larger Catechism, question #118 ↩

- S.H. Kellogg, The Expositor’s Bible: The Book of Leviticus, Chapter XXI ↩

- H.B. Clark, Biblical Law, p. 219, §§ 329-330 ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|