Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: McDurmon’s Rejection of Christendom and Embrace of Egalitarianism

Part 3: McDurmon’s Use of Sources

Part 4: The Slave Trade and Slave Breeding

Part 5: Rape

McDurmon insists that black families were routinely severed by greedy slave owners who frequently sold husbands, wives, and children separately without regards to the bonds of marriage. McDurmon also complains about the intrinsic injustices of the American legal system that stacked the deck against blacks. Let’s examine these claims in order.

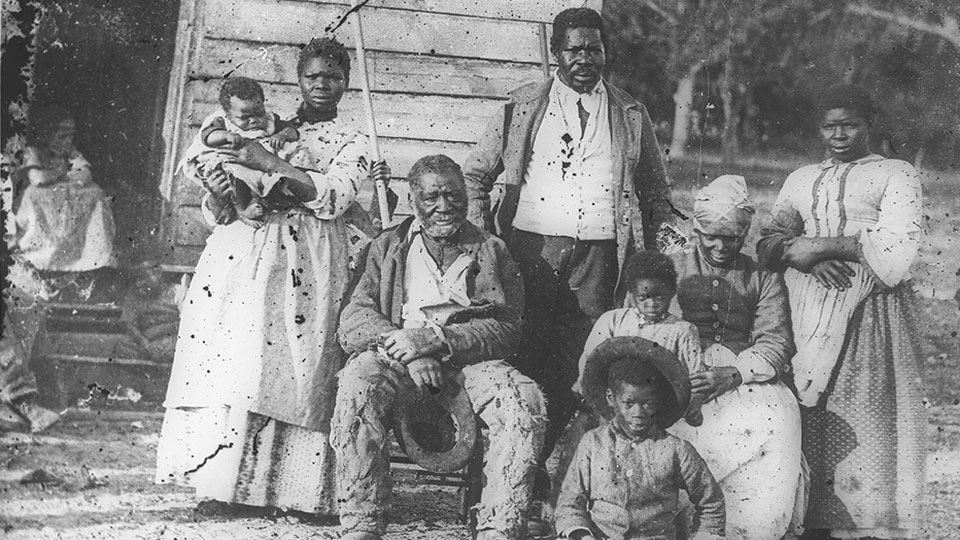

Families Torn Asunder

Joel McDurmon insists that the separation and rupture of slave families is “one of the most censurable atrocities of American slavery.”1 McDurmon argues on several occasions that masters “separated family members on a routine basis. We know that slave sales, the domestic trade, and planter migrations all forced the separation of slave families, usually permanently. Institutional slavery did this as well, usually separating children from parents or spouses from each other to different renters each year.”2 Again, “it forcibly ruptured the families of the enslaved: spouses from each other, parents from children, and more.”

McDurmon asserts that R.L. Dabney is deliberately lying about the breakup of slave families: “Not even the lowest of any of these figures could by any stretch of the imagination be honestly described as ‘not often.’ One out of four, one out of three, even one out of ten—these are not infrequencies, especially when the raw numbers are in the hundreds of thousands. Dabney had to have known better. He lived in Richmond, Virginia from 1853 until after the end of the war. Richmond was one of the key centers of the domestic slave trade during this time.”3 McDurmon concludes, “The basic fact is that the domestic slave trade ‘carried hundreds of thousands of slaves, mostly children and slaves of marriageable age, and yet virtually no child was traded with its father, nor wife sold with her husband.’”4

McDurmon relies heavily on the research of Michael Tadman to establish his case, but I have my skepticism that a book published in the late twentieth century by a state university approaches the subject in a fair or objective manner.5 One issue is that prior to their conversion to Christianity, blacks did not (and typically still don’t) exhibit an inclination to traditional family structure. Illegitimacy has been common among blacks throughout history, with a few men freely mating with many different women. This leaves children to be raised by their mothers with some help from maternal male relatives. This trend goes back to Africa, and many blacks outside of Africa revert to this condition once Christianity has diminished in influence among them. Steve Sailer points this out in his response to Thomas Sowell’s “black redneck” theory.

McDurmon also cites Herbert Gutman’s The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925, in which a slave is quoted about a master who separated husbands from their wives. However, McDurmon ignores Gutman’s conclusion in this book that most black families remained largely intact despite slavery, and only later experienced breakdown during the 1930s and 40s. This is significant because Gutman is, like most of McDurmon’s sources, a liberal academic, and he wrote Slavery and the Numbers Game against Fogel and Engerman’s now controversial work, Time on the Cross, which he considered too lenient on slavery and slave-owners.

Finally, McDurmon ignores the brilliant work of historian Eugene Genovese, who argues in his classic Roll, Jordan, Roll that many masters went out of their way to try to keep slave families intact. The image of cruel whites ripping children from their mother’s weeping arms seems to be another case of abolitionist and Jacobin mythology. Genovese writes,

Many slaveholders went to impressive lengths to keep families together even at the price of considerable pecuniary loss. . . . The choice [to cave in to market pressures] did not rest easy on their conscience. The kernel of truth in the notion that the slaveholders felt guilty about their inability to live up to their own paternalistic justification for slavery in the face of market pressure.

The more paternalistic masters betrayed evidence of emotional strain. In 1858, William Massie of Virginia, forced to decrease his debts, chose to sell a beloved and newly improved homestead rather than his slaves. . . . An impressive number of slave-holders took losses they could ill afford in an effort to keep families together. For the great families, from colonial times to the fall of the regime, the maintenance of family units was a matter of honor. Foreign travelers not easily taken in by appearances testified to the lengths to which slaveholders went at auction to compel the callous among them to keep family units together. Finally, many ex-slaves testified about masters who steadfastly refused to separate families; who, if they could not avoid separations, sold the children within visiting distance of their parents; and who took losses to buy wives or husbands in order to prevent permanent separations.6

Systematic Injustice

McDurmon claims that the courts allowed injustices to be perpetrated against slaves by not allowing blacks to testify. This allowed masters to perpetrate virtually any crime, including murder, against their slaves with impunity. “A master, fed up with a particular slave, could purposefully ‘correct’ a slave to such extremity that he by ‘chance’ died, and there would simply be no recourse for such actions. This would be especially true later when the courts would solidify the rule that blacks could not testify against whites in a court of law. At that point, a master could literally beat a slave to death in front of an entire body of other slaves and get away with it.”7

Eugene Genovese provides a much-needed corrective: “On the whole, the racist fantasy so familiar after emancipation did not grip the South in slavery times. Slaves accused of rape occasionally suffered lynching, but the overwhelming majority, so far as existing evidence may be trusted, received trials as fair and careful as the fundamental injustice of the legal system made possible. . . . The scrupulousness of the high courts extended to cases of slaves’ murdering or attempting to murder whites. In Mississippi during 1834-1861, five of thirteen convictions were reversed or remanded; in Alabama during 1825-1864, nine of thirteen; in Louisiana during 1844-1859, two of five. The same pattern appeared in other states.”8

McDurmon’s duplicity on the subject of criminal justice is apparent from his selective usage of statistics. A good representative example of this is when he discusses the propensity of black men to rape: “in South Carolina…between 1785 and 1865, only a total of 58 slaves were executed for rape (which amounts to only .725 executions per year).”9 McDurmon cites this statistic to argue that the white perception of black men as prone to rape is false, but the scarcity of blacks executed for rape demonstrates that whites were committed to justice in the prosecution of crimes.10

Whites did not have the intention of using the law as a casual pretext for murder. An example from the late-nineteenth-century South demonstrates the attitudes that prevailed among whites on the subject of criminal justice. In 1888 in the town of Central, South Carolina, a mentally ill white man raped a black girl who later died from the trauma. A group of black men caught the white man and lynched him. Six blacks were arrested; three were found not guilty, one was let go on a mistrial, and two were convicted but then pardoned by the white-run judicial system. The white-run newspaper of the area ran an editorial defending the lynching as justified: “While the citizens of Central cannot but condemn violence, they think if ever a case of lynching was justified, this is the one. White men have been lynching Negroes for the same thing since the war, and having set this example, they should not grumble if the Negroes imitate them when a like occasion arises.”11 Whites could have used false rape allegations as a pretext for murdering innocent black men if they had desired to do so, and if the number of blacks had been high, you can bet that McDurmon would have made that exact argument. But whites did not do this, because as Genovese points out, whites held to a higher standard of justice informed by Christian ethics.

In the next article we will examine McDurmon’s claims about the punishment of slaves. McDurmon suggests that blacks were routinely punished in gruesome and cruel ways that demonstrate the sheer horrors of American slavery.

Read Part 7: Cruel Punishment and Corporal Mutilation

Footnotes

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 8668-8669). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 6286-6289). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 8765-8769). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 8740-8742). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- The book is Michael Tadman, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989) ↩

- Genovese, Eugene D., Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage Books, 1976, p. 453. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 668-672). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- Genovese, Eugene D., Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage Books, 1976, pp. 34-35. ↩

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 8811-8812). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- For more information on lynching, see “The Lynching Myths.” ↩

- Fordham, Damon L., True Stories of Black South Carolina. Arcadia Publishing, 2008. p. 53. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|