Joel McDurmon found himself stumped this past summer when a black pastor asked him why he was so driven to involve himself in “the race issue.” McDurmon could not come up with a reason. Even at the time of publishing his article “The race issue: why I am doing this,” he admits continued difficulty in identifying his motivation.

He seems to have spent a number of months pondering the question; but somewhere along the way, perhaps after being visited in a dream by his Uncle Leon, he remembered back to his seminary days when a “theologically conservative” pro-Clinton black minister said he would sure love to use nineteenth-century Southern slavery as an excuse to dip his hand into the white man’s pocket. It was at this moment, upon recollecting the cupidity of a fellow Marxist seminarian, that McDurmon suddenly realized he could justify robbing whites and redistributing to blacks if only he dressed up the whole scheme in the biblical guise of restitution, or reparations.

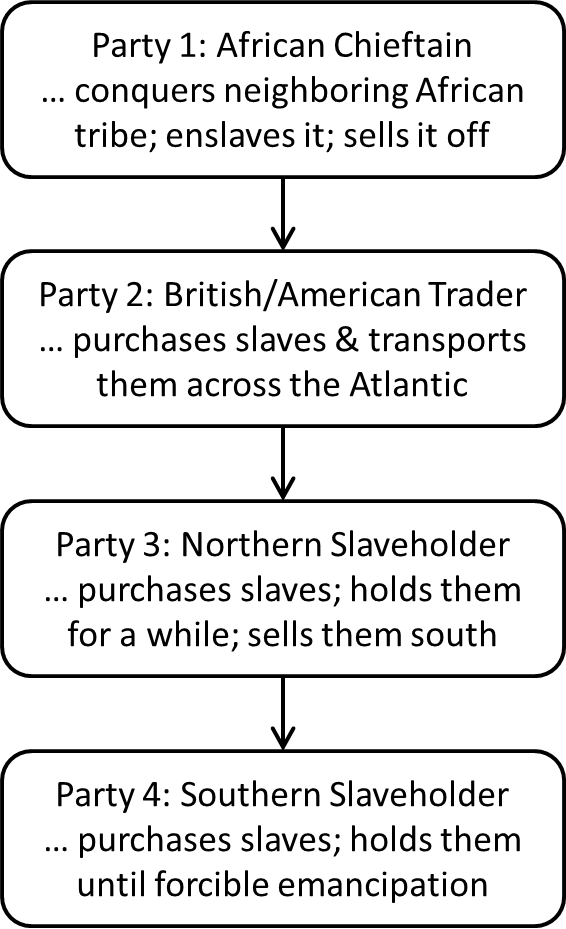

As a matter of historical background, recall that American slavery went through a centuries-long process to become what it ended up as in 1865 when it was terminated. In most cases, it originated with some African chieftain conquering neighboring tribes and making slaves of them, at which point he would transport them to the western African coast and trade them for rum. The purchasers were white (often British and American) traders who would load the slaves on ships, carry them across the Atlantic, and sell them on the American continents and isles. All of the American colonies purchased these slaves at one point or another and utilized their labor. Notably, when the Northern states abolished slavery in the early nineteenth century, they did not generally emancipate their slaves, but instead sold them south, where slavery was still legal. In this way, they did not forfeit the equity in their slaves but received compensation for them. Finally, within a few decades of the abolition of slavery in the North, the war had eliminated slavery in the South as well.

Of all the components of this complex machine that did, over time, create the existence of the 1865 slave, are we to denigrate the final element, the Southern slaveholder, as the sum of all wickedness in this process? He did not conquer or capture anyone, did not enslave anyone, and did not transport anyone across the Atlantic. Yet McDurmon demands no reparations from the African captors, the traders, or the Northern sellers, but slaps the onus exclusively on the South:

[Reparations is] a matter of justice delayed and yet due, and should have been exacted from the public wealth of the South to begin with.

He means, I think, that the North should have exacted these reparations from the South at the conclusion of the war. That is, he views Party 3 as not only guiltless in this process, but as the proper judge, jury, and executioner of Party 4.

Furthermore, when the hot potato of slavery lands in the lap of Party 4, what duty does McDurmon require of Party 4 to remedy its supposedly illegitimate possession of slaves? Can anything be reasonably demanded beyond simply disbanding the relation? The previous parties certainly did no more than that (and not without compensation), yet McDurmon seems dissatisfied with that idea:

It was not simply enough that “the slaves were freed” after the Civil War.

In order to put a lower bound on how much McDurmon thinks the South owed/owes in reparations, we have to understand the full cost the South paid, both in emancipation itself and in the violent method of emancipation that was carried out. The average value of a slave in 1860 was about $800, and there were, conservatively, 3.5 million of them, representing a total value of $2.8 billion ($75 billion in 2017). This is the amount the people of the Confederate States forfeited just by virtue of emancipation.

Next, add the 300,000 Southern men who were killed in the war, and whose deaths set the Southern economy back a hundred years. Sherman and Grant burned plantations to the ground and destroyed cotton gins, bridges, railroads, and other infrastructure, commandeering millions of bales of cotton, bushels of grain, and livestock. Sherman’s tirade against Georgia alone resulted in a loss to that state of $100 million, 80 percent of which was sheer vandalism.

Also, we should credit to the South’s balance sheet all the positive contributions made to the slaves over the years. They were fed, sheltered, and clothed so that their living conditions and state of being exceeded anything on the continent of Africa, or anywhere else in the world, at the time. Surely that is worth something. R.L. Dabney makes the case:

Was it nothing that [the Africans] should be brought, by the relation of servitude, under the consciences and Christian zeal of a Christian people, in circumstances which most powerfully enlisted their sense of responsibility, and gave free scope to their labour of love? Let the blessed results answer, of a nation of four millions lifted, in four generations, out of idolatrous debasement, “sitting clothed, and in their right mind;” of more than half a million adult communicants in Christian churches! And all this glorious work has been done exclusively by Southern masters; for never did foreign or Yankee abolitionist find leisure from the more congenial work of slandering the white, to teach or bless the black man in any practical way. This much-abused system has thus accomplished for the Africans, amidst universal opposition and obloquy, more than all the rest of the Christian world together has accomplished for the rest of the heathen.1

Yet McDurmon insists that, indeed, all of that contribution was nothing. In spite of the feat of civilizing the Africans and making them fruitful and industrious—an anomalous singularity in the history of mankind—the descendants of Southern slaveholders are still in debt to the Africans.

We might make one final argument that a century and a half has elapsed now. The perpetrators, victims, and any witnesses are long gone so that it would be quite impossible to know who owned slaves, which slaves they owned, how long they owned them, how many hours each day they were worked, and so forth. Even if owning slaves had been in any way against the law at the time, statutes of limitations would come into play because of the utter impossibility of rendering a just and equitable outcome after so much time. In fact, even a statute of limitations is meaningless at this point because the Southern slaveholder is an extinct species: not a single one remains anywhere but in the grave. Surely social justice must be satisfied by now!

No, no. McDurmon will have none of it:

Restitution is a biblical law issue, and justice denied is God’s wrath stored up. This will not go away, ever. . . . This is not a statute of limitations issue. God has no statute of limitations for social sin and injustice.

Let not even the disintegration of the perpetrators’ corpses impede the sacred cause of financial remuneration! Track down the sons of the sons of the sons of the sons of the culprits if necessary. And if they have no sons, never mind that; make someone else pay!

This rapacious appetite of egalitarianism consumes whole civilizations if left unchecked. It was for this reason that the Apostle Paul required such as McDurmon to be barred from the communion of the church:

Let as many servants as are under the yoke count their own masters worthy of all honour, that the name of God and his doctrine be not blasphemed. . . . If any man teach otherwise, and consent not to wholesome words, even the words of our Lord Jesus Christ, and to the doctrine which is according to godliness; he is proud, knowing nothing, but doting about questions and strifes of words, whereof cometh envy, strife, railings, evil surmisings, perverse disputings of men of corrupt minds, and destitute of the truth, supposing that gain is godliness: from such withdraw thyself. (1 Tim. 6:1-5)

Abolitionism is a fully arrayed assault on the social hierarchy ordained by Providence and on the words of Christ Himself. Its adherents have always been enthralled with the idea of deriving financial gain from their pretended godliness, and McDurmon is no exception. He actually praises the Marxists for having, as he claims, a more biblical view of race than Dabneyan theologians:

Dabney . . . failed to address the core issues of race and slavery in a biblical way—and that was what mattered most. . . . For want of that biblical view of race, social relations, and slavery, etc., and for want of the pulpit doing its job, the slack was picked up by radicals, atheists, Marxists, and leftists of all sorts.

The Marxists picked up the slack for Dabney! One can almost hear the bellowing, thunderous laughter of a retributive Providence in the background.

When all is said and done, McDurmon plainly identifies himself with the antichristian plunderers of Southern civilization and seeks to instigate a sort of proletarian revolution that will redistribute the white man’s wealth to the black race. McDurmon’s case for restitution is so feeble and ridiculous that it cannot be taken as a serious attempt to execute biblical justice. It is but a pharisaic cloak for the theft, bloodshed, and devastation for which Jacobinism insatiably thirsts.

Footnotes

- R.L. Dabney, A Defense of Virginia, p. 180. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|