In this day and age it is always odd to see something that seems pro-white to receive accolades from the usual dispensers of anti-white hatred. Sources like the New York Times, the cuckservative church, and even liberal activists do not heap praise upon white people for being proud of being white, or even for wanting to improve things for white people. The price of admission to modern-day elitism is to deny one’s allegiance to the Bible, its moral code, one’s white ancestry and identity, and anything else smacking of heteronormative, cisgender, patriarchal, Bible-thumping, white pride.

Knowing the rules of the road can be helpful to avoid accidents when driving. So too knowing the rules of our politically correct society can be helpful to avoid falling into the traps laid here, there, and everywhere designed to ensnare unsuspecting people in error, guilt, and sheepish behavior.

When I saw the title of J.D. Vance’s book, Hillbilly Elegy, ranked among the top “must-reads” of 2016 according to many evangelical leaders, I naturally suspected something was afoot. Why would the ardent proponents of white genocide want their sheep to read a book that, judging by its cover, is about a white population?

Obviously, it must be to further convince them of the propriety of anti-white mindsets and activism, right?

I picked up the book from my library with a skeptical, but still relatively open, mind. After learning that the author had risen from literal rags to the not-quite-riches but still solidly upper-middle class life, including a law degree from Yale, I tried to check my white, conservative, skeptical privilege and give Mr. Vance a fair shake.

I learned early on that the 30-something’s young life was in many ways like my own — and like that of many white Americans. He did not have a “Leave it to Beaver” home. He did not have a functional home or a permanent set of parents. He did not grow up wondering only about what college to attend or what outfit would look best on him at school.

Instead, he had what many white Americans would call a normal life. He had a mother who had been salutatorian of her high school graduating class, but who went in and out of jail and rehab as often as the proverbial black welfare queen. He had a grandma who had the mouth, the temper, and the lethal inclinations of his future peers in the U.S. Marine Corps. His father figure was a drunk grandpa who was great at fixing cars, and great at raising his voice and getting into violent altercations with his wife. He had an elder sister who grew up far too soon and became the closest thing to a guardian angel that the author ever had. He grew up regularly eating fast food for dinner, watching TV inappropriate for a child, never knowing how to earn or keep money, hiding from the loud and scary arguments his elders engaged in, and on more than one occasion lying to law enforcement to ensure that he wouldn’t end up in a foster home.

The most memorable incidents in Mr. Vance’s young life both involved his mother. On one occasion, she ordered him into the car, and then accelerated madly and told him that she was going to crash the car and kill them both. The author’s decision to jump into the back seat and try to brace himself with two seat belts triggered his mom’s temper even more, and she pulled over the car to beat him. It turned out to be a life-saving decision. The author jumped out of the car and ran away, into a homeowner’s backyard, and screamed at the middle-aged lady who was peacefully floating in her swimming pool, to call the police because his mom wanted to kill him.

I’ve never been in precisely that situation, but suffice it to say that such things do happen in white America. They happen to too many white children, and too many white adults perpetrate such evil behavior.

The other most-memorable occasion in his youth took place years later when, as an adolescent, his mom — who had a nursing job — came to him with a cup. She demanded that he give her his urine so that she could provide a clean sample to her employer. Otherwise, she insinuated, she’d be out of a job, and woe-is-me-what-will-I-do? This was about the 500th time in his all-too-young life that he’d been confronted with a choice that no youngster should ever have to face: to protect himself and his honor, or bail out his parent. What parent should require his or her child to bail him out? If one has to bail the other out, isn’t it supposed to be the mature, wiser, responsible adult who bails out the immature, naive child? Sadly, that was not the household or culture in which Mr. Vance grew up.

I would be incorrect to allege that Mr. Vance’s sufferings, or the evils perpetrated by his parents (his biological father was an exception: he converted, became a disciplined Christian, and led an upright life from which the author willfully walked away), grandparents, and older relatives, are as typical of the white lower class as of the lower classes of other ethnic groups. Unfortunately but typically, the author and his publicists have made his Elegy out to be the proof of that wrongheaded thesis.

People cognizant of racial realities know that race does matter, and that on the whole, the whiter a community is, the more functional, safe, and free it will be. While in sheer numbers a majority-white country (like the United States) may have more whites than blacks on welfare or in trouble with the law, the percentages of those groups are not equal. Non-whites commit a disproportionate amount of crime and are dependent on government assistance at far higher rates than whites, in whatever country you look at.

However, it would be equally reckless to ignore that what Mr. Vance endured as a child is to be found in some measure across the racial divide. The sort of domestic violence, sexual immorality, incapacity for self-government, wasteful materialism, indolence, indebtedness, dependence on economic and parental assistance from older generations, drug use, children born out of wedlock, parental neglect, and so on that Mr. Vance endured and/or witnessed are to be found among lower-class whites as well as among lower-class non-whites.

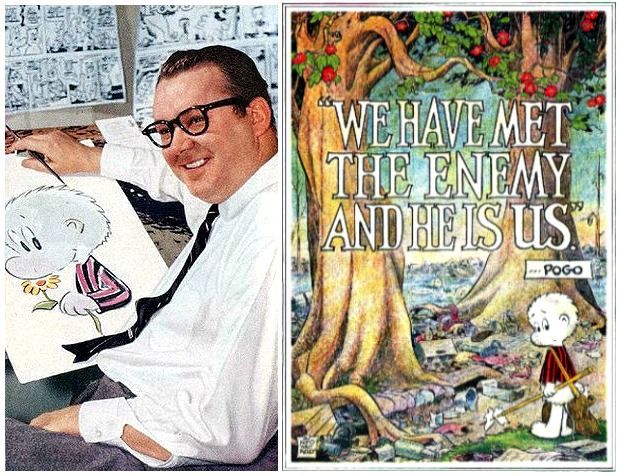

As a white person who believes that we should take care of our own, the moral and social failings of our own kin have to be our responsibility. We would love it for blacks to shore up the black community, and we respect those amongst them who do so. As whites, we must do the same. There are a few things I’d suggest that we need to do to accomplish this. The first thing is to own the problem as our own. It is not the government’s, not society’s, and not non-whites‘ problem. It is a white problem. We need to also not take refuge in the fact that, as I stated earlier, other communities have seemingly worse problems than ours. Just because a lower-class white community has less incidence of gang violence, it still may very well be rife with meth and heroin addicts, abandoned children, and truly lost souls. As whites, who are naturally inclined towards individualism and resistant to those telling us what to do, we have in some ways a harder time admitting that we have a problem as a community, and a harder time admitting to one another that the problem is literally right in front of us. As the comic strip character Pogo famously said, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

One of the things preventing us from admitting, owning, and rectifying our problem is our individualism. Another one is a bit harder to overcome: our unwillingness to recognize ourselves as a distinct community. Whites are notoriously anti-white. Even Mr. Vance, who knew that he had come from and represented a distinctively white population, had a hard time admitting that he had an ethnicity. Whenever whites like Mr. Vance admit that they do, in fact, have an ethnic identity, they immediately feel like they have to apologize for that fact. The reason is because whites have been conditioned to link admissions of white identity with fear of punishment for having that identity. Whether through white guilt for slavery, or the Holocaust, or conquering the Americas, or patriarchy, or the Crusades, or a number of other alleged sins against humanity, white men and women have been conditioned to associate white identity with pain, guilt, and grief. Not surprisingly, then, it is much more comfortable for whites to deny that they collectively have an identity, to let the federal government lump us in as individuals with non-whites who have problems, and to thus pass the whole burden of improving our lives and communities to a bureaucracy that neither recognizes our ethnicity nor has an interest in promoting the welfare of our community. For decades we’ve done this, and in addition to the many other anti-white measures that permeate our society, this dynamic has made it very difficult for whites to take ownership of their distinct communities and the problems within them.

I’ve seen firsthand the eagerness with which private and public leaders in nearly all-white communities look to Uncle Sam to fix the problems that they, through their own initiative and efforts, could solve faster, better, and cheaper. But they’re loath to trespass on their neighbors’ personal space. They are unwilling to admit that they have a role to play as members of not only a geographically-defined community, but a community tied by blood, soil, religion, and language. They don’t want to admit that they’re white and that their common ethnic heritage obligates them to stand up for, and stand up to, one another.

There’s another reason why whites won’t fix white problems: class division. Mr. Vance hit on this repeatedly, and it is one of the strongest points of his book. In addition to showing the problems of broken people and broken families in white America, his book excels at showing how successful white Americans basically live in a separate universe from their dysfunctional, poorer, co-ethnics. During his time at Yale Law School, the author described the confusion he experienced due to not knowing the unwritten codes according to which the mostly-upper class school operated. He told about the time when, at a function that would lead to job offers, he had to make a phone call to his Asian girlfriend from the bathroom so he could ask her to explain how to use the nine utensils he had in front of him at his spot at the dinner table. Yes, a country boy from Appalachia probably won’t have any idea of what to do with the spoons, forks, and so on that a Connecticut scion would use with familiar ease. Neither did he know how to make sense of the conflicting advice he heard from his faculty and peers at the law school. Grades are important…but not important. Be aggressive about getting clerkships…but don’t pick the wrong one, and don’t ask judges about their requirements. What he came to realize later on was that it was the social network which his richer peers had, not their grades, that opened doors to them that remained closed to him. It wasn’t anything malicious on their parts; it was just that he was from a completely foreign culture that taught him nothing of the etiquette and mores of the upper-class legal world.

Lastly, and tragically, many of our own people live according to what Mr. Vance called “learned helplessness.” We despise it when we see non-whites living and talking this way — it is essentially the role of self-pitying, self-victimization. “I committed the crime, I didn’t show up at work, I didn’t stay faithful to her…but it’s someone else’s fault!” The mindset that fixes us permanently in the role of helpless, innocent victim and fixes the world out there as the permanent, omnipotent aggressor disables our moral agency. It cripples us because, in that worldview, there is nothing we can do to improve our situation. Ergo, work and self-improvement are pointless. At best, we can lash out and make a momentary, nihilistic impact on whomever we see as our tormentors. Islamic suicide bombers and Dylann Roof equally fall into this category, along with millions of people like the white man who, as Mr. Vance described in his book, complained about Obama and bragged about not working, while living on welfare with his eight children from different women.

Mr. Vance’s problem was not unsolvable. Thanks to several people — who, interestingly, were predominantly Asian — he found his sea legs and made his entry into the legal profession. Mr. Vance now is not only a published author but also an investment banker in San Francisco, where he lives with his Hindu wife and two dogs.

Yes, the country boy from Appalachia found his refuge in a straight-talking, but functional, Hindu girl whom he met at law school. He chose a functional, liberal life over a dysfunctional, white conservative life. Her parents don’t yell and throw things at each other. She doesn’t tell him to [expletive] himself and threaten to walk out on him when they have a disagreement. However, he described how as a practicing lawyer he had to unlearn these, and other, anti-social behaviors he had learned from his elders. He had to disassociate his dysfunctional upbringing from his functional life because if he hadn’t, he would have been dragged down and swallowed in the vortex of brokenness from which he had barely escaped.

That is a dilemma that we should prevent our children from facing. If we white parents and grandparents don’t ensure that our white homes are places of peace and stability — not anger and anxiety, like the author experienced — how can we convince our posterity that they should follow in our steps? If we can’t balance our checkbooks and stay sober, what reasons will they have to adopt our faith and follow its moral precepts? If we can’t stay committed to and love our spouses, why shouldn’t they cling to whatever functional, peaceful person they happen to come across? It’s hard to convince a battered, terrified child to stick with his native race, religion, or political philosophy when he associates his native identity with people who are brutal, loathsome, and morally inferior to himself.

Our problem as a people is not unsolvable. The conclusion that the author and his apologists drew from his life are incorrect. The answer to white dysfunctionality is not deprecating, explaining away, or miscegenating away, one’s native race, religion, and culture. It is exactly the opposite. As we often talk about in our podcast, it is Christ who gives us the command, and the power, to improve ourselves and to help others improve themselves.

By embracing one’s racial identity, and following the precepts Christ gives us – as Mr. Vance’s biological father did, which led to a happy, peaceful household for himself and his second family – country boys from North California to South Alabama can live in peace and prosperity all across the land. In Christ and in the nobility He has given us through our ethnic identities, country boys can not only survive, but thrive.

Deus vult.

| Tweet |

|

|

|