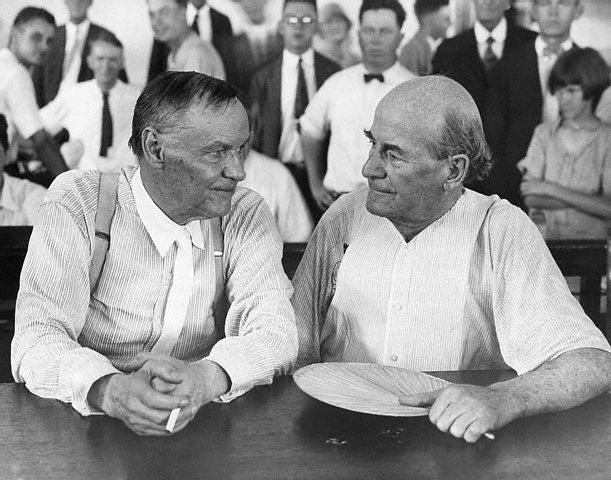

Jerry Bergman of Answers in Genesis has written an article about William Jennings Bryan’s role in the Scopes trial, which took place in 1925 in Dayton, Tennessee. The Butler Act was a Tennessee law that prohibited teaching in public schools any theory which denied the biblical account of man’s origin. This law was challenged when John Thomas Scopes taught the theory of evolution in defiance of the Butler Act. The trial emerged after civic leaders in Dayton collaborated and decided that the trial would be good publicity and thereby stimulate the local economy. The ACLU offered to defend any teacher who violated the Butler Act by teaching evolution, and Scopes agreed to stand trial in what would become one of the most famous cases in the history of American jurisprudence. William Jennings Bryan was recruited as a prosecuting attorney, while Clarence Darrow volunteered his services for the defense.1

What is often forgotten is that the prosecution actually won the case. Scopes was fined $100 (although the conviction and the fine were later waived on appeal), and the Butler Act would remain in force until 1967. The play and film Inherit the Wind would portray the events of the Scopes trial as a contest of religious bigotry against rational scientific inquiry and freedom of speech and religion. The Scopes trial represented a watershed moment in the fundamentalist-modernist debate in many Protestant denominations, and it is also a famous example of how competing worldviews disagree on the tenets of free speech and the public role of religion. But was the Scopes trial about “racism” or eugenics? That is the position of Jerry Bergman in his recent article. Bergman draws on such luminaries as Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould to make his case.

Bergman cites Dershowitz to assert that the advocates of evolution in the early twentieth century included “racists, militarists, and nationalists.” Dershowitz attributes resistance against immigration to Darwinian evolution: “The anti-immigration movement, which had succeeded in closing American ports of entry to ‘inferior racial stock,’ was grounded in a mistaken belief that certain ethnic groups had evolved more fully than others.” While it may be the case that some Americans were motivated to strengthen immigration restrictions on the basis of evolutionary theory, evolution was by no means the origin of American immigration restrictions. America was a self-consciously white nation from its very inception.2 Immigration and naturalized citizenship were restricted well before the twentieth century, based not only on a national preference for immigrants to be of the same ethnic stock, but doubtlessly also on a concern that third-world immigrants would, by their inferiority, harm the country. Immigration restriction increased with the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, but these measures were by no means unique, nor were they necessarily motivated by Darwinian evolution.

The problem with all of this is that Bergman’s understanding of history is far too dependent upon left-wing Jewish academics. This is the same Stephen Jay Gould who lied in his famous book, The Mismeasure of Man, in criticizing the “racist” biases of scientists like Samuel George Morton. Bergman’s article lacks citations from contemporary accounts of the Scopes trial that would establish racial policies as a focus of the trial. This is, frankly, because the Scopes trial had nothing to do with racial differences, immigration policy, or equality. It’s as simple as that. It does not follow that Darwinism has no implications upon the question of race and human dignity; Bergman correctly notes that William Jennings Bryan was concerned about how Darwinism distorts the dignity of humanity. But this is because Darwinism robs nature of teleology, degrading the dignity and purpose behind all races, including the white race. Hence Bryan’s anti-Darwinism doesn’t make him an egalitarian or a proponent of modern politically correct racial policies. The truth is quite the opposite. What did William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow actually believe about race?

Clarence Darrow

Darrow was the most prominent attorney for the defense of John Scopes, as well as an agnostic and staunch defender of Darwinian evolution. If Jerry Bergman and Answers in Genesis are correct about Darwinism’s supposedly “racist” worldview, then we would expect Darrow to be an exemplar of this “racism.” The reality is just the opposite. As a consistent Darwinist, Darrow lacked belief in any distinctions rooted in divine purpose. If nature is sufficient to explain the existence of life, then there is no purpose in distinctions such as race or sex.3 All these differences boil down to minute variations in molecules. That’s it. Darrow was more than willing to take this worldview to its logical conclusion.

In 1901, Darrow delivered a lecture entitled “The Problem of the Negro” to the mostly-black Men’s Club in Chicago. In this lecture Darrow stated:

When Douglas and Lincoln were debating in Illinois, Mr. Douglas, as his last and unanswerable statement asked, “Would you want your girl to marry a Negro?” and that was the end of it. Well, that is a pretty fair question, and I am inclined to think that really that question is the final question of the race problem; and not merely the catchword of a politician. Is there any reason why a white girl should not marry a man with African blood in his veins, or is there any reason why a white man should not marry a colored girl? If there is, then they are right and I am wrong. Everybody may have his own taste about marrying, whether it is between two people of the same race or two people of a different race, but is there any reason in logic or in ethics why people should not meet together upon perfect equality and in every relation of life and never think of the difference, simply because one has a little darker skin than the other? It does not always follow even that they have darker skins. There are very many people who have some colored blood in their veins and who have a lighter skin.

Is there any reason why an Indian should not associate on term of perfect equality with the white man? Even our most fastidious people, you know, invite the East Indian gentlemen to come to their dinners and their parties and exhibit them as great curiosities in the best families and the best churches. When the Buddhists came over here at the time of the World’s Fair we thought they were great people, and their skin was as dark as any of you people here tonight, and there was no reason why they should not have been treated on terms of perfect equality with the white people of the United States; neither is there any reason why a person of dark skin, who has been born and bred in the United States, should be considered any different whatever from a person of white skin, and yet they are. The basis of it is prejudice, and the excuses given are pure hypocrisy; they are not good excuses, they are not honest excuses.4

The remainder of the lecture leaves no doubt that Darrow was a committed liberal on the issue of race. His stated views would not gain political traction until the 1960s, and even then they would not become entrenched in the mainstream until the 1990s. For all of Jerry Bergman’s pontificating about eugenics, white supremacy, Hitler, and the Nazis, he provides no evidence that Clarence Darrow entertained anything like any of these views. While there certainly were men influenced by Darwinism who maintained a robust perspective on race realism, there is no evidence that this was the focus of the Scopes trial. It certainly wasn’t the focus for Clarence Darrow. Darrow was a man who took Darwinist ideas about the cosmos to their logical conclusion. If naturalism and materialism are true, then all creatures, including humans, are simply matter in motion. This has profound implications for morality, and leaves no room for preserving distinctions rooted in divine teleology. Darrow’s comments make this undeniably clear, as he expresses ignorance of “any reason in logic or in ethics” why miscegenation should be prohibited.

William Jennings Bryan

Jerry Bergman accurately points out that William Jennings Bryan was concerned about the implications of Darwinism for human dignity. What does not follow is that Bryan was therefore opposed to race realism or race-based nationalist policies. It is true that Bryan was no traditionalist. Bryan held many progressive and liberal ideas that were prominent in his day, and he was influential in moving the Democratic Party away from its laissez-faire and small-government Jacksonian roots during the Democratic National Convention in 1896. Bryan resisted modernism and was orthodox on matters of doctrine, but his Protestantism was tainted by pietism, and consequently he campaigned for prohibition and women’s suffrage. He was a three-time nominee for the presidency by the Democratic Party, and he served as Secretary of State in the Woodrow Wilson administration. Bryan was also admired by Democratic presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry Truman. Nevertheless, Bryan believed in the existence and importance of race, as virtually all conservatives and liberals did in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Bryan had an unpublished memoir that he did not complete before passing away, in which Bryan praised his white Christian roots. Bryan identified himself “as a member of the greatest of all races, the Caucasian race.”5 Bryan’s relationship with the South was also complicated. At times, early in his political career, Bryan seemed resentful of Southern resistance to the expansion of power by the federal government. Later on, he became more sympathetic to the South. He gave a speech in 1923 before the Southern Society of Washington, D.C., in which he defended segregation on the grounds of self-preservation. At the Democratic National Convention in 1924, Bryan was instrumental in striking down a resolution condemning the Ku Klux Klan.6

Bryan was also opposed to imperialism. Many imperialists of the time believed in what Kipling dubbed “the white man’s burden.” Bryan’s opposition to imperialism was rooted in ethnonationalist grounds, comporting with the biblical teaching on the divine ordinance of national boundaries, that God has made out of Adam the different nations and tailored them to their natural homelands and environments (Deut. 32:8-9; Acts 17:26-27). In a speech simply called “Imperialism,” Bryan explains why whites will never permanently colonize lands near the equator. “The white race will not live so near the equator. Other nations have tried to colonize in the same latitude. The Netherlands have controlled Java for three hundred years and yet today there are less than sixty thousand people of European birth scattered among the twenty-five million natives.”7

It is clear that Bryan’s opposition to imperialism wasn’t grounded in political correctness or egalitarian assumptions. Bryan believed that the different nations and races were created to dwell and thrive in particular environments, and therefore the white race should not crusade in foreign lands. Most of Bryan’s beliefs were certainly liberal for his time: he was a proponent of political equality for women, a graduated income tax, and a more expansive federal government. Nevertheless, Bryan retained a robust view of racial identity and racial pride. There is no reason to believe that Bryan saw his legal battle in the Scopes trial as a battle over the reality or importance of racial distinctions. Bryan did not believe that a concern over the true dignity of humanity as created in God’s image was opposed to a proper understanding of racial or ethnic pride.

Conclusion

This is a disappointing article from Answers in Genesis. Jerry Bergman overlooks too many important details about the personal beliefs of Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan in his overview of the Scopes trial. Bergman fails to provide evidence that either Darrow or Bryan considered the Scopes trial as a referendum on race or race-based policies. The article is also disappointing, for it lends credence to the idea that evolution is simply a white male construct. Bergman states that black churches and women took leading roles against the spread of evolutionary ideas. The examples given might technically be correct, but it isn’t accurate to downplay the importance of white male Christians in the fight against Darwinism and for creationism. By promoting the idea that the fight against Darwinism is really a fight against white male “racism” and “sexism,” Bergman is simply playing to the galleries.

The owners of Answers in Genesis know that the campaign against politically incorrect “isms” is a popular one. The idea is that if they can somehow make the association between Darwinian evolution and “racism” or “sexism” stick, then they can finally convince mainstream society to embrace creationism and reject Darwinism. The tactic isn’t working, and this article is just one more example of dishonesty by Answers in Genesis when addressing the race issue. It’s a pity that authors like Jerry Bergman aren’t more forthcoming on the issue of race, especially when his other articles that don’t address race seem quite good.

Footnotes

- Information regarding the Scopes trial was taken from its Wikipedia article. ↩

- For an overview on this American history, see “The Founding Fathers Revisited: Part 1, The Original Founders and Christian Supremacy” and “The Founding Fathers Revisited: Part 2, The Creation of the United States and the Establishment of White Supremacy” by Jan Stadler, as well as my article, “Who Does America Belong To?” ↩

- See my article on Darwinism’s egalitarian morality and Nil Desparandum’s article, “Miscegenation, Sodomy, and the Coherence of Nature-Hating Egalitarianism“. ↩

- Clarence Darrow, “The Problem of the Negro,” lecture delivered to the Men’s Club in Chicago, May 19, 1901. ↩

- William Jennings Bryan, “Unpublished Memoir.” Referenced in Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan, pp. 278-279. ↩

- For more information on Bryan’s view of race, see here, and for Lawrence Auster’s assessment, see here. ↩

- William Jennings Bryan, “Imperialism,” 1900. Cited from Voices of Democracy: The U.S. Oratory Project. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|