Part 1

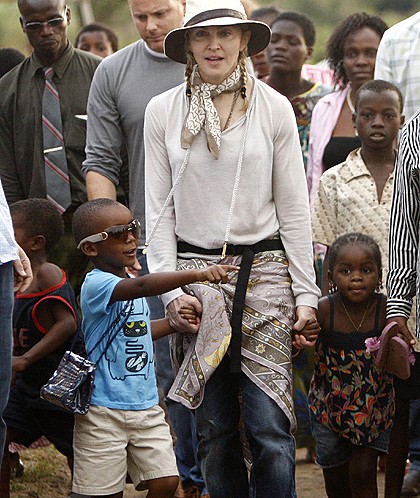

The last article was an introduction to the issue of adoption and my concerns with the contemporary practice of adoption. My initial concern was specifically with the practice of whites adopting children from different races, but this led me into an investigation of adoption in general. My conclusion is that adoption, as it is currently practiced, is not in conformity with biblical teachings concerning the hereditary nature of the family and charity to orphans. My suspicion is that the modern phenomenon of adoption is rooted in a desire for Christians to seek approval from the world by emulating a current social trend. Adoption has gained social prominence largely because of the example set by pop culture celebrities who seek to adopt non-white children. This is not to deny the loving, generous motives of many who do engage in adoption – only to note the fairly perspicuous social motives animating this trend as a whole.

Another influence that I believe drives transracial adoption is white ethnomasochism. Whites are bombarded by anti-white propaganda virtually everywhere they go. The world’s evils are blamed on whites, and adopting non-white children might be considered an excellent way to repel accusations of racism. These efforts are still largely unsuccessful, and the prominence of whites in adopting children of other races is often met with even more accusations of racism, since whites are perceived as wanting to turn other people white through forced assimilation. While it is impossible to judge everyone’s motives for seeking to adopt children of a different race, there are issues that need to be addressed. In this article we will look at how adoption and inheritance are addressed in the Old and New Testaments.

Adoption in the Law

In order to understand adoption from a biblical perspective, we need to see how the concept of adoption is applied in the Bible. It may come as a surprise that the word “adoption” is mentioned relatively few times in the Bible, and these are confined to Paul’s epistles. While the specific word “adoption” isn’t used frequently in the Bible, related concepts are certainly perceivable in both the Old and New Testaments. In fact, it is necessary to understand the Old Testament background and context concerning inheritance in order to understand the applications made by the Apostle Paul in the New Testament concerning adoption. Historically and biblically, adoption, properly speaking, does not refer to caring for orphans by taking them into one’s home and raising them as one’s own children. This drive to care for orphans fundamentally by incorporating them into one’s household and daily domestic life is, historically, a very recent development. Adoption, instead, has principally involved inheritance – the designation of a legal heir – usually in the absence of an heir among the natural children of a family, but also in the event that a closely-related orphan needs a home.1

The Israelites practiced a system of inheritance that genuinely recognized the immediate family, but did so within the family’s larger tribal identity. Property was divided among individual families who were grouped together according to their tribe. Property was passed on from the father to the sons, with the chief portion of a family’s estate being inherited by the eldest son, a double portion relative to the other heirs (cf. Deut. 21:15-17).2 Within this context, consider a case law involving Zelophehad, a man of the tribe of Manasseh. The book of Numbers catalogs the heads of the families that settled Israel after the Exodus. Zelophehad lacked a son to inherit his property (Num. 26:33), so his daughters requested that they be allowed to inherit their father’s estate before it passed to more distant male relatives (Num. 27:4). Moses brought the matter before God, and the daughters of Zelophehad were granted their father’s inheritance (Num. 27:6-7), as were all daughters without brothers (Num. 27:8). This resolved the problem for Zelophehad’s daughters partially, for they emerge again later in the book of Numbers.

Since Israel was a patriarchal society where property was predominantly held by the patriarch and passed down to his sons, there was a concern that property passing to daughters would upset this tribal balance if heiresses married into different tribes, since their ancestral property would pass into their husbands’ hands and, as well, these women’s sons – their heirs – would belong to their fathers’ tribe (Num. 36:3-4). This would create tribal confusion, effectively depriving the women’s tribe of its collective inheritance within one generation. The solution was to stipulate that the women who were to inherit should marry only within their father’s tribe (Num. 36:6-9). This does not itself constitute adoption, but it does demonstrate a weighty concern governing Israelite considerations of inheritance: the inheritance was not to be doled out to outsiders, not even to tribal outsiders within the people of God. Similarly, any act of adoption, since adoption necessarily involves inheritance, must accord with this principle restricting inheritance to one’s extended family and kin.

Another way in which an heir could be provided was stipulated within the law of levirate marriage, as stated in Deuteronomy 25:5-10. When a man died without any children, his brother would marry his widow, and the firstborn of the union would be posthumously deemed the heir of the deceased father. “If brethren dwell together, and one of them die, and have no child, the wife of the dead shall not marry without unto a stranger: her husband’s brother shall go in unto her, and take her to him to wife, and perform the duty of an husband’s brother unto her. And it shall be, that the firstborn which she beareth shall succeed in the name of his brother which is dead, that his name be not put out of Israel.” (Deut. 25:5-6). This new child would, we presume, inherit not only the father’s name but also his full material, proprietary, and landed inheritance. Like the law of Numbers 36, the levirate law presumes bequests to be most properly given to one’s own bloodline: in Numbers, the concern was to keep inheritances within the tribe; here, it is to keep inheritances within the family, so that the widow would not carry the assets to a new husband. The nominal and material inheritance of this childless man was to be continued in the offspring of his wife and biological brother, i.e. in his biological nephew (or, if he lacked a biological brother, a similarly close child), not just in anyone. Thus the levirate law reaffirms the Mosaic principle governing inheritance: that it ought to be reserved fundamentally among one’s own kin for the common good of the family and extended family (tribe), as well as the nation.

From the precepts developed from the cases of the daughters of Zelophehad and levirate marriage, we can reasonably explain how the Old Covenant people of God would have understood adoption. Since adoption involves not merely the admittance of another person into one’s family’s domestic life, but also the designation of that person as a true child, having a right to inheritance alongside the natural-born children, it follows rigidly that adoption must be circumscribed by considerations of inheritance. This is true regardless of moderns’ prevalent emphasis upon providing daily domestic benefits for an orphan – a higher standard of living, greater vocational opportunities, and most importantly, parental affection and love – rather than upon providing that orphan with an inheritance. For even though moderns focus upon providing orphans with a superior quality of life rather than upon providing them with an inheritance, they still must concede that adoption necessarily involves inheritance. If an orphan is not made a true child but merely placed within one’s household’s daily life, then he is not truly adopted, as we will see is clear from the New Testament texts on adoption (and as is admitted by moderns when they strongly affirm the equality of adopted children with biological children). Consequently, even though the Law does not explicitly discuss adoption – incorporating a child born to other parents into one’s own family, legally designating him as one’s own child – its discussion of inheritance starkly demarcates the permissibility of adoption only to those cases where inheritance-transferal is permissible. And as we just saw, the Law’s emphasis to reserve inheritance for one’s kin – one’s family and tribe first – limits this discussion. Though other objections will arise in defense of modern adoption practices, a potent prima facie case against such practices is evident from the Mosaic Law’s limitation upon inheritance.

This prima facie case is strengthened by the fact that although most modern Christian adoptive practices are motivated by a concern of charity for orphans – indeed, they frequently cite such passages as lucid justification – the Old Testament’s heavy emphasis upon the care for the fatherless or orphans is never linked conceptually or practically with adoption. We will discuss these passages on orphans in a subsequent article, but for now note that the simultaneous presence in Israel of legislation restricting inheritance to one’s kin and of legislation requiring care for the fatherless constitutes an even stronger argument that the Israelites would have discouraged, if not forbidden, the adoption of unrelated orphans; for it implies that Israelites ought to have charitably benefited orphans without dividing their inheritance among them. We can then expect, given these legal restrictions, that any adoption practiced among Israel would have involved only the adoption of relatively close family members, e.g. of a close cousin or nephew or niece without parents. As we will also see, there is at least one specified instance of adoption in the Old Testament, as Esther is adopted by her older cousin Mordecai. This case confirms our points concerning adoption among one’s near kin.

The Law, merely by its discussion of inheritance, clearly precludes the idea of transracial, transnational, and even transtribal adoption. We can therefore judge that contemporary adoption as practiced by whites generally, and white Christians specifically, is rooted in error. First, Christians have divorced the biblical injunction to care for orphans from the familially- and socially-oriented biblical precepts restricting inheritance to natural children or, when necessary, to close relatives. Second – and what is likely an even stronger argument, even if Mosaic case laws do not explicitly discuss it – many Christians have ceased to think of the family as being thoroughly linked to heredity. I have seen it argued by multiple Christians that there are two separate but valid ways to form a family, either by natural birth or by adoption, the latter making possible a multiracial family. (Secularists likewise argue that adoption allows for the possibility of sodomitic and other bizarre, antinatural households.) But this clearly does not comport with what the Bible teaches concerning the family. Far from being a normal or even preferred way to form a family, the practice of adoption should be performed with a mind to inheritance and therefore to close family connections. Because the purpose of adoption is to join an outside child to one’s own natural-born children, adoption is to mimic the basic and normative pattern of ordinary procreation, and therefore must respect hereditary considerations. Adoption is limited by concerns of blood precisely because it is meant to approximate the ordinary generation of natural-born heirs. It is not to be established as a completely disconnected yet equally valid means of children-acquisition; such a view would deny that the family is ideally and normatively hereditary. This hence contradicts the theory that adoption is a conceptually separate alternative to natural birth, for such a theory confuses the biblical teachings on the family.3 The practical result of this would generally limit adoption to one’s close relatives according to their need – a conclusion which harmonizes with the independent argument for hereditary adoption from the Mosaic laws governing inheritance.

If Christians are to properly understand the true nature of adoption and the family, then any idea that suggests that the family need not be hereditary in nature, or that adoption can or should occur between people of different nations and races, must be discarded. God cares about preserving the inheritance of the tribes and nations whom He has created (Deut. 32:8-9; Acts 17:26-27). The inheritance laws given in Numbers and Deuteronomy are convincing evidences of this fact, as is a simple consideration that the family is normatively hereditary. The reason for much of the confusion over the concept of adoption has to do with several New Testament passages that deal with adoption. It is to these passages that we must now turn our attention.

Adoption in the New Testament

Adoption in the New Testament must be understood in light of what has been established by the Old Testament, and as we will see, we find a great harmony between them. The word “adoption” appears exclusively in Paul’s epistles, although the concept is not entirely foreign to the Gospels (cf. John 1:12-13). Paul declares that God made Abraham heir of the world (Rom. 4:13), and that all Christians are through faith the seed of Abraham and thus co-heirs with Christ (Rom. 8:16-17; cf. Gal. 3:26-29; 4:5; Eph. 1:5). These verses form the heart of the belief that Christians are all, in some sense, spiritual orphans whom God has adopted for the sake of His Son Jesus Christ. We are, as it were, without any spiritual father or inheritance until the Father draws us into His household and entitles us to the eternal inheritance of the Kingdom. Hence Paul strongly links adoption and inheritance – as the Old Testament does, and as the term historically signifies – and moreover the rest of the New Testament speaks of our salvific inheritance (Matt. 25:34; Acts 20:32; 1 Cor. 6:9-10; Gal. 3:18; 5:21; Eph. 1:11; Col. 1:12; 3:24; Heb. 6:12; 9:15; 1 Pet. 1:4; Rev. 21:7). Although Christ is the only-begotten (John 3:16) and firstborn Son of God (Col. 1:15), and therefore heir of all creation in His own right (Heb. 1:2; 2:10), Christians are made sons of God alongside Christ: we are, through faith, made to be sons of God by grace analogously to how Christ Himself is the only-begotten Son of God by nature, and we are entitled to the same eternal heavenly inheritance which Christ merited.

Christians in favor of modern adoptive practices will sometimes cite these verses speaking of our spiritual adoption as having obvious reference to the common practice of foreign adoption today. But I contend that this reading is mistaken. As stated above, adoption would not have been practiced among the ancient Israelites except in rare cases to bring in an heir or to tend to the needs of an orphaned relative, for inheritance was restricted to one’s kin. Similarly, the practice of ancient Rome at the time of Christ quite intentionally connected inheritance with adoption, using adoption to attain heirs for childless patrician families. There simply was not a historical practice of charitably adopting unrelated orphans into one’s home, and therefore there was no such practice which Paul meant to reference in his description of our spiritual adoption. Any attempt to justify modern adoptive practices from these New Testament texts must find supporting argumentation, as Paul is certainly not referring directly to these practices.

To supply this argumentation, modern Christians more frequently use these passages to justify such practices as an overtly clear picture of the Gospel. God adopted orphans from all tribes and nations into His household; therefore we ought to do the same, bringing foreign orphans into our own household. The divine example, it is argued, makes foreign adoption to be not merely permissible in principle but highly commendable and even obligatory, providing the onlooking world with a painting of redemption.

The main problem with this line of thought is its confusion of physical and spiritual realities. Orthodox Christianity recognizes the validity of both categories, and the New Testament amply speaks of these glorious spiritual realities: thus, for example, Christians are in a very real sense the members of one household of faith (Gal. 6:10) and of one holy nation (1 Pet. 2:9). But one unfortunate way to confuse these two categories – physical and spiritual – is to unduly draw practical conclusions by stretching the spiritual analogies past their intended meaning. If we were to take 1 Peter 2:9 as implying that all Christians should form into a singular nation – form a one-world government! – or, worse, if we were to take Galatians 6:10 as implying that all Christians should be treated as part of one household, all Christian children being interchangeable, we would clearly be guilty of abusing these spiritual truths. Identifying the community of believers as one family or nation is intended to communicate the deep unity we ought to have – the unity and cooperation proper to a household or nation – not to abolish distinctions among physical households or nations. When Christians then suggest that our “real” family or our “real” nation is the Church, from the verses above, they not only draw absurd conclusions but contradict verses that speak to the continued importance of physical families (e.g. 1 Tim. 5:8) and physical nations (e.g. Acts 17:26-27; Rev. 21:24-26).

We can draw further absurd implications from this physical/spiritual confusion. As an analogy of salvation, we, through faith, are said to be incorporated into one body with many members (1 Cor. 12:12-27). Should we take this as instructing us to pursue a sick medical procedure linking all believers’ bodies into one? Again: Scripture teaches that we are, in the Church, the bride of Christ (Eph. 5:22-32). Should we then argue for the practice of “communal marriage” in such utopian societies as the Oneida Community? Or should we argue for sodomite marriage, given that the Church includes males? Should we argue for incestuous marriage, as the Church includes some of Christ’s own family members? Clearly, we should not stretch these spiritual analogies to morally govern the physical reality to which the spiritual analogy refers; we should let the intended points of connection in the text guide our usage of the analogy without autonomously extrapolating unintended features of the analogy to apply to physical realities.

But this is precisely what modern Christians do in arguing for modern adoptive practices. The text always depends upon the reader’s prior familiarity with the nature and norms of various physical realities – households, nations, bodies, marriages – to help the reader grasp the nature of our salvation, so it would be foolish to take these spiritual analogies as fundamentally supplying the moral norms of that physical reality itself – and especially foolish to take them as supplying new moral norms. We do not take this to be true for the moral norms governing families, nations, bodies, and marriages; we should do the same with adoption. The New Testament, while it assumes that adoption is indeed intrinsically permissible, nevertheless designs its references to adoption to evoke in the reader the nature of ordinary cases of human adoption: where an orphaned child, lacking parental protection and any inheritance to support himself, is aided by relatives who generously share their household and inheritance with this child. Given the norms governing inheritance and the nature of the family as normatively hereditary, this is how adoption should generally look. Scripture then takes these relevant facts of orphanhood and inheritance, as situated in ordinary cases of adoption, and describes our glorious salvation in such terms. But Scripture never points to the foreignness of the orphans as a relevant or (much less) ideal feature of the adoption in consideration, and consequently it is a nature- and Scripture-twisting misuse of this beautiful attestation to our spiritual adoption, to take it as justifying foreign adoption.

The modern movement within Christianity promoting the adoption of ethnic and racial foreigners and severing the concept of family from heredity and procreation stems from the error of considering physical reality unimportant because in Christ we are constituted as one spiritual household and nation. This error downplays the importance of physical families as a means of exalting the supposedly greater unity present in the Church, but there is no need for Christians to do this. God has achieved this unity through the internal ministry of the Holy Spirit, and this unity exists whenever true Christians call upon the name of the one true God. Denigrating our place within our own families and nations in order to demonstrate our loyalty to the Church would be like denigrating our relationship with our spouses in order to demonstrate our loyalty to Christ. It should be obvious that our physical and spiritual identities are not in competition with each other, but both serve to complement the other. As important as Christian unity was to the Apostle Paul, he never renounced his loyalty to his physical nation (Rom. 9:3) and continued to teach that the family and clan have a continued importance in Christian society (1 Tim. 5:8). Christian unity is best expressed in homogeneous societies in which trust can flourish. Ethnic and racial heterogeneity creates an atmosphere of distrust and unhappiness, and is thus opposed to Christian unity. Once homogeneity is achieved in Christian nations, these nations can then extend charity and encouragement to other Christian nations in the knowledge that their own identity will not be threatened.

Conclusion

This concludes our discussion on the biblical understanding of adoption as it is established by the Law and applied in the New Testament. Adoption must always be understood within the context of other biblical teachings, such as primogeniture and tribal property ownership. The fact that these principles are being forgotten at a time when adoption, especially transracial adoption, is greatly popular should alert us to the unscriptural character of modern adoption practices in most cases. The Law, through its restriction of inheritance to one’s kin, implicitly allows for adoption only as an accommodation to circumstances in which a related heir is needed or in which a household can support a related orphan. Adoption is a blessing in that it preserves the inheritance that God has given to our respective families (2 Kings 18:31; Isa. 36:16), but is not principally considered a means of charitably benefiting the world’s orphans.

The New Testament similarly uses the language of adoption in conjunction with concerns of inheritance. Adoption makes us co-heirs with Christ, the only-begotten Son of the Father. Spiritual adoption is not intended to substantially alter our understanding of natural adoption, just as the unity of the “household of faith” (Gal. 6:10) and of the “holy nation” of believers (1 Pet. 2:9) is not intended to replace natural families or ethnic nations that exist due to heredity and lineage. Adoption as it is taught in both the Old and New Testaments is rooted in the idea that heredity matters and is important, for heredity is proper to the family itself. Never is there any hint that adoption nullifies the importance of our hereditary relationships with our tribal kinsmen; rather we see that heredity is assigned paramount importance as something worth preserving. In our next article we will discuss the biblical teaching on care for orphans, which is a separate concern from adoption.

Read Part 3

Footnotes

- As stated in Part 1, the Roman practice of adoption was explicitly for the purposes of inheritance. ↩

- See this article for a decent overview of primogeniture in the Bible. ↩

- This especially contradicts the view, held by Bojidar Marinov, that adoption, as a “judicial” choice to incorporate a person into one’s household as heir, is the basic and universal practice, and that adoption frequently (but not necessarily) occurs on the occasion of procreation. Such a view completely inverts the biblical and commonsense understanding of familial relationships. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|