After the Netherlands, the homeland of a great deal of the Boer people, handed over control of the Cape Colony to the British in 1806, some 12,000 inhabitants of the Colony, primarily from those of Dutch, French Huguenot, and German stock, started an inland migration which would later be known as the Great Trek. These Voortrekkers, as they became known, consisted of two groups: the semi-nomadic Trekboers and some more established farmers, known as Grensboere. The main contributing factors for the migration were the Trekkers’ discontent with British rule, the Anglicisation of the traditionally Dutch Calvinist Church, and the indifference of the British rulers towards conflicts with the black tribes (or Bantus, as they were known) on the colony’s eastern frontier. Another reason might also have been the farmers’ search for fertile land, which was becoming scarce in the British Colony. Piet Retief was chosen by the Trekkers to lead the migrating company, and he drew up a Voortrekker Manifesto, in which he importantly stated the following in points 5 and 6: “We are resolved, wherever we go, that we will uphold the just principles of liberty; but whilst we will take care that no one shall be held in a state of slavery, it is our determination to maintain such regulations as may suppress crime and preserve proper relations between master and servant. We solemnly declare that we quit this colony with a desire to lead a more quiet life than we have heretofore done. We will not molest any people, nor deprive them of the smallest property; but, if attacked, we shall consider ourselves fully justified in defending our persons and effects, to the utmost of our ability, against every enemy.“1

Most Trekkers settled in unoccupied land in what would later be known as the Orange Free State (between the Orange and Vaal Rivers) and the Transvaal (the area between the Vaal and Limpopo Rivers). A small contingent under leadership of Retief himself, however, migrated to the northern part of the Natal Colony and there Retief negotiated a land treaty with the Zulu King Dingane. Shortly after signing a treaty with Retief, Dingane reneged on his agreement and killed Retief along with more than half his contingent–including many women and children. Many of the Boers left in Natal were calling for a complete emigration out of Natal, while others were of the opinion that the murder on Retief must first be avenged before any other actions should be taken. The other Trek leaders, Piet Uys and Andries Potgieter, soon arrived with support. However, after the death of Uys, Andries Pretorius, at the time still living in the Cape, was called on for additional help, and when he arrived in Natal in November 1838, he was immediately chosen as the new leader. On 9 December, Pretorius proposed that the Trekkers make a vow to God, that, if He were to deliver them, they would celebrate this day in their generations as a sabbath and as the birthday of their people. The elder Sarel Cilliers authored the vow and it was written down by Pretorius’s secretary Jan Bantjies. Every evening for the next week the Voortrekkers repeated the vow in order for the men to realize their complete and utter dependence upon God for their deliverance in the upcoming battle where they knew they would be vastly outnumbered.

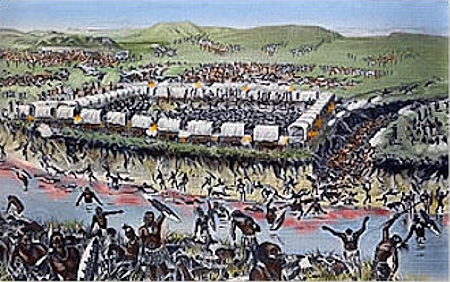

On 15 December, the Boer scouts spotted the Zulu army approaching. Pretorius gave the commands that the Trekkers should form a circle or “laer” with their ox-wagons. They decided not to attack the Zulu army, but rather to remain on terrain of their own choosing. The Zulus did not attack in the night due to their superstitious beliefs, but during the night of 15 December 1838, 6,000 Zulus, or just under half the Zulu army, crossed the Ncome River (later known as Blood River) and started massing around the laer. The elite Zulu forces didn’t yet cross the river, however, but remained at a safe distance.

At dawn on 16 December 1838, the mighty and feared Zulu army, 14,000 men strong, attacked the laer, where some 430 Voortrekkers opposed them. The Trekkers were thus outnumbered about 33 to 1. After two hours and four unsuccessful attacks, Pretorius commanded a group of horsemen to leave the encampment and engage the Zulu in order to disintegrate their formations. Although the Zulus initially withstood the attack for some time, and at several points even looked to get the upper hand over the horsemen, rapid losses did eventually cause them to scatter. This occurred until late into the afternoon of 16 December, when the Trekkers’ horsemen chased the retreating Zulu warriors. Some 3,000 Zulu warriors were killed that day. Because the Ncome River turned red with the blood of the Zulus, it was renamed Blood River. Miraculously, not a single Voortrekker died in battle that day, and only three were lightly wounded. Four days later, the Voortrekkers found Dingane’s settlement, Ngungundlovu, completely destroyed. Retief and his men’s bones were found and buried.2

It is because of this deliverance that the Boers could go on to form the independent Natalia Republic (1839-1843), the South African Republic (1852-1902) and the Republic of the Orange Free State (1854-1902) and so establish the first indigenous, non-colonial Western governments in Africa. This achievement would have been completely impossible, had it not been for the providential blessings from the Almighty. Because of this, it was of absolute importance for the Boer people to live in complete dependence upon Him and live according to the Reformation motto SOLI DEO GLORIA in all spheres of life.

Although this has at times been the case, the promise to God to celebrate 16 December as a sabbath has been rather inconsistently kept by the Boer people over the years. Shockingly, there was a time in the people’s history, only a few years after the battle, that only Sarel Cilliers sanctified that day as a sabbath and stayed true to the vow, and it is told that not even Andries Pretorius himself kept the vow. During the National Party’s rule of the country between 1948 and 1994, the day was celebrated as a public holiday in South Africa. However, since the Marxist takeover of 1994, the holiday has been changed to become the so-called “Day of Reconciliation.” Today, conservative Boers across the country still continue to celebrate the vow and the victory that God graciously gave to the Trekkers that day, as the birth of a people. The day is also a day of hope and humiliation before God, whose eternal decrees are all-encompassing, and in contemporary times the day is often used to remind the people that even the current Pan-African Marxist government serves its divine purpose in the glorification of God.

From the history behind the day of the vow and the battle of Blood River, both the embattled Boer minority in South Africa, as well as those in the Western World who seek to preserve their heritage, can learn a few lessons. First of all, the Trekkers and especially Cilliers’s trust in God’s power to deliver is an example to live by. Of course, it also shows that God keeps his biblical promises to deliver his children from danger, and that we can still today call upon God’s promises in the Old Testament, like those in Deuteronomy 28:1-14 and II Chronicles 7:14. We are also reminded that we must pay our vows (Ps. 50:14-15); it is today widely recognized that the Boers lost the second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) because of their neglect of the vow. The most important lesson the Battle of Blood River holds for the Western world today, in the midst of the peril caused by humanist rationalism, secularisation, and immigration from the Third World, is the age lesson of Psalm 146:3: “Do not put your trust in princes, nor in a son of man, in whom there is no help.” It is time for White Christians everywhere to openly acknowledge our complete dependence on God and proclaim to the world that we might be in this world, but we are certainly not of it, and that our salvation lies in Christ alone, to whose glory we must dedicate our entire existence.

Footnotes

| Tweet |

|

|

|