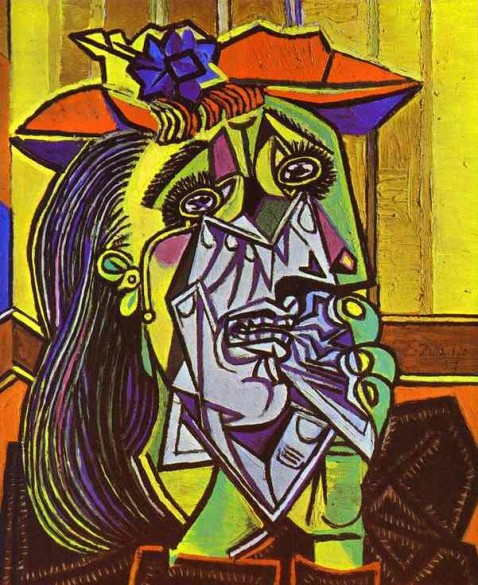

Shown above is Millie Brown of London, who creates her works of “art” by drinking and then vomiting different colors of dyed soy milk onto white canvas. One of her completed pieces:

Being homeschooled growing up, I went to a lot of museums, since we had the flexibility to take educational trips during slow hours and avoid crowds while the rest of my peers were cooped up in classrooms. I loved going to science and history museums, although my reaction to art museums was the polar opposite. I found viewing room after room of art created a visceral disgust and repulsion similar to watching a dog defecate. This feeling extended to my studies as well. Art, poetry, and literature, while certainly not my favorite, were at least generally bearable until we hit the nineteenth-century portion of the subject, particularly the latter half of the century, at which point the visceral disdain returned. I was far too young to understand my reaction and, in fact, while remaining firm in my dislike, I was generally unable to articulate the reasons behind it until my first or second year of college, when I read Wilmot Robertson’s book The Dispossessed Majority for the first time.

If I made a list of the top five most influential books in my life, The Dispossessed Majority would be on it. One of the things I like most about the book is that Wilmot Robertson is an Anglo-American who takes an honest yet firm Anglophile view. This stands in stark contrast to other works of European nationalism, which too often, even if written by Anglos, take an opposing Germanophile or Nordophile view. I have intentionally attempted to replicate Robertson’s Anglophile view here on F&H.

The Dispossessed Majority first discusses the definition, philosophy, and genetics of race, and then uses that as a foundation on which to discuss the history and racial makeup of the United States, highlighting both the majority and minority groups. Robertson defines the majority as the Protestant, English-speaking Anglos – Scots, Welsh, Cornish, and some Irish being included here – who founded and built America, along with the Germanics, Nordics, and other Western and Northern Europeans who were part of the initial pre-1860 immigration and who quickly and easily assimilated into the culture that the Anglos instituted and maintained. Robertson also discusses the minority which is at odds with the majority and includes groups like Hispanics, Negroes, Jews, Middle Easterners, Asians, Southern European Catholics, and Eastern European Orthodox. Robertson further divides the minority groups into assimilable and unassimilable groups. A Catholic Polish or Orthodox Russian family living in the Polish or Russian section of New York City in 1920 was part of the minority, while their great-grandchildren living in middle-class Pennsylvania in 2010 are generally part of the white American majority. These great-grandchildren have had their language, culture, politics, and even religion largely adapted to be in line with that of the original Anglos and may have even intermarried with descendants of the original majority. Contrast this to the other minority groups like Negroes or Jews who, despite being in America for 400 years for the former and for 150 years for latter, remain largely unassimilated and unassimilable.

Robertson traces the fundamental conflict between majority and minority not only through U.S. history, but through the different areas of culture, demonstrating how the majority is badly losing the struggle. Robertson touches on how this majority-minority struggle has played out in religion, education, politics, economics, law, foreign policy, and of course art. The title of this post is the same as chapter 18 of The Dispossessed Majority, and I will be using passages from that chapter to outline why I and many other white Americans feel revulsion and disconnect rather than beauty and inspiration from modern art.

Robertson begins with the assertion that great art requires, as a prerequisite, both a homogeneous racial and cultural audience with which the artist can align his bias, tastes, and worldview, and an aristocratic class springing naturally from that homogeneous racial and cultural group to financially support and guide the native school of art.

A basic assumption of contemporary Western thought is that democracy is the political form and liberalism the political ideology most generative of art. The more there is of both, it is generally conceded, the greater will be the artistic outpouring, both quantitatively as well as qualitatively. The corollary assumption is that once art has been liberated from the dead weight of caste, class, and religious and racial bigotry, its horizon will become limitless.

Of all modern myths, perhaps this is the most misleading. If anything, art, or at least great art, seems to be contingent on two social phenomena poles apart from democracy and liberalism. They are:

(1) a dominant, homogeneous population group which has resided long enough in the land to raise up from its ranks a responsible and functioning aristocracy; (2) one or more schools of writers, painters, sculptors, architects, or composers who belong to this population group and whose creative impulses crystallize the tastes, tone, and manners of the aristocratic leadership into a radiating cultural continuity. . . .

If Florence and Athens are admitted to be semi-aristocracies or at least aristocratic republics, it is evident that all the great artistic epochs of the West have taken place in aristocratic societies. There has been art in non-aristocratic societies, often good art, but never anything approaching Greek sculpture and drama, Gothic cathedrals, Renaissance painting, Shakespeare’s plays, German music, or Russian novels. . . .

Liberal dogma to the contrary, such popular goals as universal literacy are not necessarily conducive to great literature. The England of Shakespeare, apart from having a much smaller population, had a much higher illiteracy rate than present-day Britain. Nor does universal suffrage seem to raise the quality of artistic output. When Bach was Konzertmeister in Weimar and composing a new cantata every month, no one could vote. Some 220 years later in the Weimar Republic there were tens of millions of voters, but no Bachs.

The presence of an aristocracy does not guarantee great art, but the absence of one certainly prevents it from generally being produced.

Next, the presence of the minority artist, both in a society ruled by the majority and in a society ruled by the minority, is discussed:

The fatal flaw that denies the minority artist a place among the artistic great is his inherent alienation. Because he does not really belong, because he is writing or painting or composing for “other people,” he pushes a little too hard, raises his voice a little too high, makes his point a little too desperately. He is, inevitably, a bit outré – in the land, but not of the land. His art seems always encumbered by an artificial dimension — the proof of his belonging.

In a non-aristocratic, heterogeneous, fragmented society, in an arena of contending cultures or subcultures, the minority artist may concentrate on proving his “non-belonging.” Instead of adopting the host culture, he now rejects it and either sinks into nihilism or returns to the cultural traditions of his own ethnic group. In the process his art becomes a weapon. Having sacrificed his talent to immediacy and robbed it of the proportion and subtlety which make art art, the minority artist not only lowers his own artistic standards, but those of society as a whole. All that remains is the crude force of his stridency and his “message.” . . .

Not only high art but all art seems to stagnate in an environment of brawling minorities, diverse religions, clashing traditions, and contrasting habits. This is probably why, in spite of their vast wealth and power, such world cities as Alexandria and Antioch in ancient times and New York City and Rio de Janeiro in modern times have produced nothing that can compare to the art of municipalities a fraction of their size. The artist needs an audience which understands him – an audience of his own people. The artist needs an audience to write up to, paint up to, and compose up to – an aristocracy of his own people. These seem to be the two sine qua nons of great art. Whenever they are absent great art is absent.

How else can the timeless art of the “benighted” Middle Ages and the already dated art of the “advanced” twentieth century be explained? Why is it that all the cultural resources of a dernier cri superpower like the United States cannot produce one single musical work that can compare with a minor composition of Mozart? Why is it that perhaps the greatest contribution to Twentieth-century English literature has been made not by the English, Americans, Australians, or Canadians, but by the Irish — the most nationalistic, most tribal, most religious and most racially minded of all present-day English-speaking people. Modern England may have had its D. H. Lawrence and the United States its Faulkner, but only Ireland in this century has assembled such a formidable literary array as Yeats, Synge, Shaw, Joyce, O’Casey, Elizabeth Bowen, Paul Vincent Carroll, Joyce Carey, and James Stephens. If, as current opinion holds, liberal democracy, internationalism, and cultural pluralism enrich the soil of art, then these Irish artists bloomed in a very unlikely garden. . . .

Much of Western art, particularly in the United States, is now in such a stage of dissolution. The surrealist painters, atonal jazz musicolgists [sic], prosaic poets, emetic novelists, crypto-pornographers, and revanchist pamphleteers say they are searching for new forms because the old forms are exhausted. Actually they are exhuming the most ancient forms of all — simple geometric shapes, color blobs, drum beats, genitalia, four-letter words, and four-word sentences. The old forms are not exhausted. The minority artist simply has no feeling for them, for they are not his forms. Since style is not a commodity that can he bought or invented, the avant-garde, having no style of its own, can only retreat to a styleless primitivism.

The dissolution of art is characterized by the emergence of the fake artist – the man without talent and training who becomes an artist by self-proclamation and self-promotion. He thrives in a fissiparous culture because it is child’s play to bemuse the artistic sensibilities of the motley nouveaux riches, assorted culture vultures, sexually ambivalent art critics, and minority art agents who dictate the levels of modern taste. It is not so easy to deceive those whose standards of taste were developed in the course of generations.

In a homogeneous society the artist has to contend with fewer sets of prejudices. He does not have to weigh and balance his art in order to be “fair.” He need not be mortally afraid of wounding the religious and racial feelings of others. Though his instincts, opinions, and judgments often add up to bias, to the artist himself they may be the driving forces of his creativity. What really limits and devitalizes art are not the artist’s prejudices but his audience’s prejudices, an infinite variety of which exists in a vast heterogeneous society like the United States. The artist has trouble enough with one censor. When he has twenty, his art is transformed into a day-to-day accommodation.

Next, Robertson outlines the minority domination in the production of modern art.

The patterns of artistic growth and decline outlined in the preceding paragraphs have already snuffed out most of the creativity of Majority artists. Today the Jewish American writes of the Jew and his heritage, the Negro of the Negro, the Italian American of the Italian, and so on. But of whom does the American American, the Majority writer, write? Of Nordics and Anglo-Saxons? If he did and if he portrayed them as fair-haired heroes, he would be laughed out of modern American literature. Consciousness of one’s people, one of the great emotional reserves, one of the great artistic stimulants, is denied the Majority artist at the very moment the minority painter, composer, and writer feed upon it so ravenously. Besides its other psychological handicaps, this one-sided selective censorship obviously builds a high wall of frustration around the free play of the imagination. . . .

All Majority artists necessarily experience the wrenching depression that comes from enforced cultural homelessness. Of all people, the artist is the least capable of working in a vacuum. Prevented from exercising his own “peoplehood,” the Majority artist looks for substitutes in minority racism, in exotic religions and Oriental cults, in harebrained exploits of civil disobedience, in African and pre-Columbian art, psychoanalysis, narcotics, and homosexuality. On the latter subject Susan Sontag, the noted Jewish pundit had this to say:

Jews and homosexuals are the outstanding creative minorities in contemporary urban culture. Creative, that is, in the truest sense: they are creators of sensibilities. The two pioneering forces of modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aesthetics and irony.

George Steiner, a Jewish pundit, couldn’t agree more:

Judaism and homosexuality (most intensely where they overlap, as in a Proust or a Wittgenstein) can be seen to have been the two main generators of the entire fabric and savor of urban modernity in the West.

The ban on displays of Majority ethnocentrism in art — a ban written in stone in present-day American culture — also reaches back to the Majority cultural past. Chaucer and Shakespeare have been cut and blue-penciled, and some of their work put on the minority index. The motion picture of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist had a hard time being released because of the recognizably Jewish traits of Fagin. The masterpiece of American silent films, The Birth of a Nation, can no longer be shown in public without the threat of picket lines, while Jewish-produced black “sexploitation” films like Mandingo (1975), replete with the crudest racial slurs against whites, are exhibited nationwide. Huckleberry Finn was removed from the library – of all places – of the Mark Twain Intermediate School in Virginia. . . .

Outside the South, American art has been overwhelmed by members of minorities. To lend substance to the allegation that the basic tone of American creative intellectual life has become Jewish, one has only to unroll the almost endless roster of Jews and part-Jews in the arts. The contingent of Negro and other minority artists, writers, and composers, though it cannot compare to the Jewish aggregate, grows larger every day.

The minority domination of the contemporary art scene is complicated by the presence of another, as yet unmentioned minority, unique in that it is composed of both Majority and minority members. This is the homosexual cult. Homosexuals, as is well known, are one of the two principal props of the American theater, the second being Jews. Jews own almost all the large theater houses, comprise most of the producers and almost all the directors, and provide half the audience and playwrights. The other playwrights are mostly well-known Majority homosexuals. Combine these two ingredients, add the payroll padding, kickbacks, ticket scalping, and union featherbedding which plague all Broadway producers, and it is readily understandable why in New York, still the radiating nucleus of the American theater, the greatest of all art forms has degenerated into homosexual or heterosexual pornography, leftist and Marxist message plays, foreign imports, and blaring, clockwork musical comedies. It is doubtful if a new Aeschylus, Shakespeare, or Pirandello could survive for one minute in the Broadway of today.

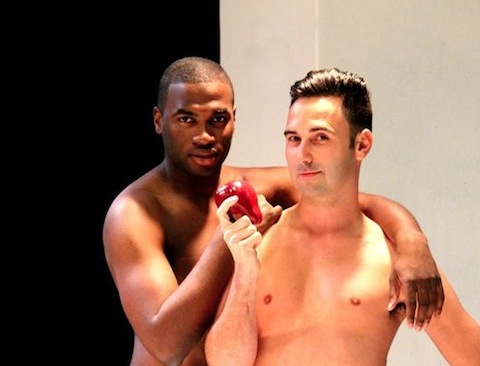

“The Most Fabulous Story Ever Told”, the Biblical creation story retold as a homosexual, interracial Adam and Steve.

But it’s not just their control of the production of art. Minority domination also extends to the industries responsible for the promotion and distribution of art as well.

The minority penetration of the communications media greatly reinforces minority cultural domination because the press, magazines, and TV are the transmission belts of art and, as such, its supreme arbiter. By praising, condemning, featuring, underplaying, or ignoring books, paintings, sculpture, music, and other artistic works the media decide, in effect, what will be distributed (and become known) and what will not be distributed (and remain unknown). A book reviewed unfavorably or not reviewed at all in the influential, opinion-shaping columns of the New York Times, the New York Times Book Review, Time, Newsweek, and a few so called cocktail-table publications has little or no chance of getting into libraries or the better bookstores.

This literary winnowing process also extends to advertising. Ads for books promoting minority racism are accepted by most newspapers and magazines. Ads for books promoting Majority racism are not. Not only would no major newspaper or magazine review The Dispossessed Majority, none of the leading weekly newsmagazines would accept paid advertising for it. Press-agentry in the form of praise from columnists and television personalities is another tested means of lending a helping hand to minority artists or to the Majority artists who specialize in minority themes. Perhaps the most banal example of the minority mutual admiration society in the arts is the practice adopted by the New York Times Book Review of having books espousing Negro racism reviewed by Negro racists. Die Nigger Die! by H. Rap Brown, a fugitive from justice rearrested after holding up a New York saloon, received a generally favorable review, although Brown wrote that he “saw no sense in reading Shakespeare,” who was a “racist” and a “faggot.”

Throughout his life and career the minority-conscious artist identifies with one group of Americans — his group. In so doing he will frequently attack the Majority and Northern European cultural tradition for the simple reason that Majority America is not his America. The Puritans are reduced to witch-hunters, reactionary pietists, and holier-than-thou bigots. The antebellum and post-bellum South is turned into a vast concentration camp. The giants of industry are described as robber barons. The earliest pioneers and settlers are typecast as specialists in genocide. The police are “pigs.” Majority members are “goys, rednecks, honkies,” or just plain “beasts.”

To accommodate the minority Kulturkampf, a Broadway play transforms Indians into a race of virtuous higher beings, while whites are portrayed as ignoble savages, and the quondam heroic figure of Custer struts about the stage as a second-rate gangster. A Hollywood film shows American cavalrymen raping and mutilating Indian maidens. A television play set in the depression years of the 1930s puts the blame for America’s ills squarely on the Majority and ends with a specific tirade against “Anglo-Saxons.” . . .

What has been described above, of course, has little to do with art. It could better be defined as anti-art. People incapable of producing or appreciating high art envy those who can. But instead of developing their rudimentary art into higher forms they concentrate on perverting and banalizing whatever art they can get their hands on. It is their way of showing their hatred for the authentic artist and all his works. Julius Lester, a much applauded Negro literary elder, identified, perhaps unknowingly, the minority artist’s real grudge – the radiant Western artistry that seems forever beyond the Negroes’ reach – when, ranging as far afield as Paris, he called for the destruction of Notre Dame “because it separated man from himself.”

The communications media and principal academic forums being largely closed to him, the Majority artist has no adequate defense against the blistering minority assaults on his culture. He must avoid praising his own people as a people – and he must avoid castigating other peoples, particularly the more dynamic minorities. The minority artist, on the other hand, wears no such cultural straitjacket. He freely praises whom he likes and freely damns whom he dislikes, both as individuals and as groups. The Majority artist, with a narrower choice of heroes and villains, has a narrower choice of theme. Lacking the drive and brute force of minority racism, Majority art tends to become bland, innocuous, emotionless, sterile, and boring.

And so I can now articulate my disgust for modern art thusly using Robertson’s language: modern art, or what liberals simply call “art,” is styleless primitivism of dumbed-down simple geometric shapes, color blobs, drum beats, genitalia, four-letter words, and four-word sentences with no connection or attempt at connection with the majority, of which I am a member, but rather a direct and malicious assault on my culture and beauty itself in the perverting and banalizing of whatever it can touch, resulting in anti-art. Millie Brown can perfect her style for vomiting dyed soy milk onto canvas all she wants, but the result will never be true art. Our modern society is specifically structured to prevent any great art from being produced.

A very unfortunate result of this anti-art’s promotion by the minority as legitimate art is the majority’s overreaction in rejecting all art, poetry, literature, and music and the suspicion of majority members who don’t do the same – particularly men (“what are you, a homo?”). We have seen above that this suspicion is often correct, but unfortunately this knee-jerk reaction has had a negative side-effect for the majority. In writing art off as the domain of the pervert and the liberal, the majority has lost one of the major pillars a people needs to maintain its identity and connection to the past, particularly amid the genocidal assault that the white American majority faces today. This is why we go out of our way here at F&H to post examples of poetry and music from before our art became anti-art, in addition to new art which rebels against the anti-art.

| Tweet |

|

|

|