Read Part 1: The Original Founders and Christian Supremacy

Introduction

As the American confederation was formed at the outset of the war, the American realms had begun to go through deep social change. Whereas America was founded along Christian supremacist lines, that absolute power had broken down and fractured to the local level. America was becoming a depository for “non-desirables” from Europe, such as Quakers, Mennonites, low-church Protestants, and Roman Catholics, along with Enlightenment thinkers and Freemasons. This dumping of non-traditional religious stock began to dilute America’s intellectual framework; consequently, social and legal accommodations had to be made to sustain order in a much more pluralistic society. Fortunately, though, Christianity and its values still prevailed militantly throughout the society, with only a small number of intellectual bandits (mainly in Boston and Philadelphia) being allowed to write and publish their secularist works.

That being said, as the colonies moved forward in time, a new power structure was beginning to develop. With landed aristocracy in full force in an agrarian world, sustained in large part by slavery, laws and customs began to take root that formed America as a white supremacist society. It was always intended to be that way.

No matter what reactionary libertarians and conservatives try to do to whitewash the history of their founders to meet the egalitarian vision of classical liberalism, the reality will always be brought to light by an ardent American leftism that hates its own founding. Therefore, it is time for American patriots to accept the reality that their Founders were Christian supremacists, white supremacists, aristocrats, and slave-owners who despised a genuine equality of the masses.

The Founding Fathers and Race

Undoubtedly there is a major intellectual disconnect between American patriots nowadays and the American patriots of the founding era. Genuine patriots, to prove they are not racist, intentionally plunge themselves into a world with no connection to their country’s founding. Otherwise, conservatives, in trying to defend their country’s honor against leftist accusations of racism and bigotry, end up defending positions that do not exist. Leftists charge that America was founded by racist whites for racist whites and that in the modern world we should feel very guilty for this, importing millions of third-worlders to prove we’re not racist. Modern patriots then respond by lauding the values of the Founding Fathers, yet without actually defending the coherent worldview they possessed that gave them their country. Based on the changes of historical trends, American patriots are now defending what was leftism at the time of the War Between the States. Even the conservative or libertarian patriot cannot bring himself to accept the reality that the Founders were racist, aristocratic, anti-egalitarian, (often) pro-slavery conquerors who believed in establishing a Republican empire in the fashion of Rome. In fact, the egalitarian rhetoric that came out of the revolutionary era was more rooted in anti-British policies and ideas, relating to parliamentary representation, than to the establishment of a new world of total equality in terms of race or economic class.

If we were to take Ron Paul and Ronald Reagan and place them at the time of the Founding Fathers, they would be horrified to find themselves run out of the Philadelphia convention as radical, ideological usurpers from a Parisian salon, with more in common with Thomas Paine than George Washington. The fact of the matter is that modern American patriots care little for what their Founding Fathers actually believed in or lived out. Citing and praising the Founding Fathers in modern America has little to do with the Founders themselves; it is rather a sort of social duty to laud them as the intellectual patriarchs of our republic – er…excuse me, democracy – to ratify and prove the narrative of the current status quo.

Quoting the Founding Fathers in American society is about as powerful and reckless as quoting the Bible out of context. In one breath, a saying of Thomas Jefferson can support the politics and ideas of anybody from Barack Obama to Randy Weaver. Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison can all be used to justify anything from white supremacy to gay marriage – and they all have been so used. If the American people genuinely cared, they would read the Anti-Federalist Papers, along with the quotes of Thomas Jefferson, and subsequently organize to rebel against the federal government and burn the U.S. Constitution as a failed document of tyranny – as was predicted by the anti-federalists.

So the question, then, for us patriots is: What did the Founders actually believe in regards to race, and why does it matter?

It matters because the American nation is without a clear identity. In the Netherlands, for example, no matter how leftist we may become, the Dutch can always default back to some symbol or idea that definitely defines us as Dutch. From the Belgaic tribes, to the Eighty Years’ War against Spain, to Calvinism, and to the Dutch resistance against the Nazis, we always have an absolute pillar of truth that can never be removed from our consciousness. The Americans, however, in contrast, have completely overturned the very foundations and origins whence they came; therefore, it is no wonder that the modern American Right apologizes for its history and lauds MLK, Jr., as a token of submission. By contrast, in Europe, we are now exonerating our heroes and legends to revive the nation, rather than to apologize for it. America needs an identity, and there is only one identity that could ever be truly American: the Caucasian Christian identity.

The Founders

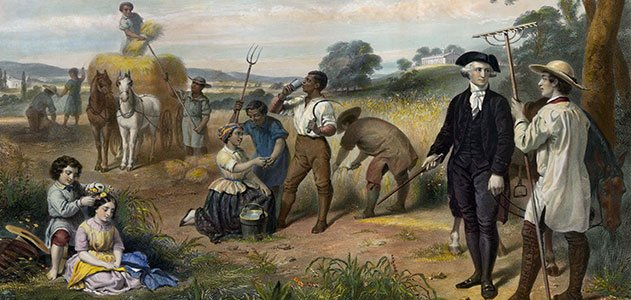

George Washington, the “father” of the American Republic, was father not only in a symbolic sense, but also in a literal sense, living out a lifestyle of true paternalism towards blacks and the land as an aristocrat. Much of Washington’s opposition to slavery was not so philosophical as it was pragmatic. Washington in his own writings lamented the slave trade, yet he held on to as many slaves as possible until, as he admits, he had just plain too many.

It appears in the historical record that Washington did not wish to comment much on the slavery issue for pragmatic reasons, as he did not want to inflame an issue he knew could divide the country. Not much exists which can prove Washington’s pro-white sympathies other than the fact that he owned non-whites and apparently felt so guilty about it that he never let them go until well after his death. That being said, Washington ultimately proved his loyalty to the Virginia gentry class by signing the Fugitive Slave Act, guaranteeing that slaves would have no safe harbor in America.

Thomas Jefferson, the supposed libertarian patriarch who penned the greatest egalitarian phrase in mankind’s history, was anything but a true egalitarian. Aristocratic by birth, Jefferson was a member of the landed gentry who ruled colonial Virginia and a prominent slave owner. Though Jefferson did not approve of slavery as an institution, it had less to do with affection for blacks than it did with slavery’s economics.

Jefferson did, however, possess an idealistic vision of North American Indians. According to acclaimed historian Stephen E. Ambrose in his book Undaunted Courage, Jefferson thought “of Indians as noble savages who could be civilized and brought into the body politic as full citizens.” Jefferson truly believed in the mythology of the noble savage, that the only thing separating the level of technological advancement between the red and white man was “caused by the environment in which the Indian lived.”

As Ambrose notes, Jefferson never took “the slightest interest in African ethnology or African vocabularies” and described blacks as lazy and prone to thievery. It was because of the Indians’ sense of higher culture inside the tribe, along with their ability to heartily survive in a fashion very similar to ancient Europeans, that Jefferson possessed a misplaced passion for them. Jefferson, along with William Clark and Meriwether Lewis, believed Indians were “ready to be transformed into a civilized citizen,” while in regards to Africans, Jefferson and his leading contemporaries “never imagined the possibility of a black man becoming a full citizen.”

Unfortunately for Jefferson, his prospect of using Indians as frontier settlers of a grand economic confederation never became realized, as it was apparent that the red man could never be conformed to the behavior and lifestyle of the white man.

But even so, when approached by French abolitionist Henri-Baptiste Grégoire about taking a more enlightened view of blacks – granting them freedom and lauding their noble history – Jefferson rejected the notions and said that he “had not modified his beliefs on the innate incompetence of Blacks.” Perhaps it was from this idea that Jefferson supported emancipation, up to the point of sending blacks back to Africa, given his fears of a slave rebellion in the United States and the negative effects slavery has on social mores.

For Jefferson, the expansion of the American republic into a continental “empire for liberty” was clearly based upon a white-dominated east, with a loyal, subservient, and enlightened Indian west; blacks would never enjoy full equality, as they could not inherently possess the requisite faculties to continue on the Anglo-Saxon legacy. Jefferson believed in Anglo-Saxon superiority and hegemony: “the Anglo-Saxons are our ancestors, and we owe to them something of our characteristics, attitudes, and institutions.”

David Opperman clarifies this statement in the featured article “Who Does America Belong To?”:

Jefferson was very motivated to preserve the Anglo-Saxon heritage of the American people and their institutions. He maintained that American institutions could not be maintained apart from an appreciation of our ancestors who created them. He worked for years on an Anglo-Saxon grammar book for university students and designed a seal with the two great Saxon warriors on it, Hengst and Horsa.

Benjamin Franklin endorsed a similar vision of expansion for Anglosaxondom, “wishing” that the numbers of Anglo-Saxons and Germans were to “increase” in North America to offset the large black and yellow populations in Africa and Asia respectively.

The War Between the States

There were many reasons for the War Between the States, no singular ideological faction having a monopoly on why it occurred. It was in part fought to preserve states’ rights, in part to defend slavery, in part as a reaction against heightening tariffs – but one thing is for certain: the war was fought by the South, to defend the institution of white supremacy against Yankee egalitarianism.

Many years before the war broke out, the nation was already beginning to discuss the abolition of slavery in a larger context of racial equality. South Carolina legend John C. Calhoun was opposed to the inclusion of Mexico into the new American confederation not because of geopolitical concerns, but because of racial concerns. In January 1848, Senator Calhoun delivered a speech before the Senate expressing his deep opposition to the annexation of Mexico along racial lines (emphasis added):

The next reason assigned is, that either holding Mexico as a province, or incorporating her into the Union, would be unprecedented by any example in our history. We have conquered many of the neighboring tribes of Indians, but we have never thought of holding them in subjection, or of incorporating them into our Union. They have been left as an independent people in the midst of us, or have been driven back into the forests. Nor have we ever incorporated into the Union any but the Caucasian race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the first departure of the kind; for more than half of its population are pure Indians, and by far the larger portion of the residue mixed blood. I protest against the incorporation of such a people. Ours is the Government of the white man. The great misfortune of what was formerly Spanish America, is to be traced to the fatal error of placing the colored race on an equality with the white. That error destroyed the social arrangement which formed the basis of their society. This error we have wholly escaped; the Brazilians, formerly a province of Portugal, have escaped also, to a considerable extent, and they and we are the only people of this continent who have made revolutions without anarchy. And yet, with this example before them, and our uniform practice, there are those among us who talk about erecting these Mexicans into territorial Governments, and placing them on an equality with the people of these States. I utterly protest against the project.

Fortunately, Calhoun’s position prevailed, and Mexico was not included into the Union, only the predominantly white parts like Texas and the unsettled West. The debate, though, did not end here. It was more for political rather than racial reasons that the Yankee states did not want the South to acquire any more land in its sphere, leading to the continued expansion of slavery.

As is often said, time moves slower in the South. This is true from an ideological perspective as well. Since the Revolution, the Enlightenment and Unitarian tradition began to accelerate its proliferation throughout the North and manifest itself within the Transcendentalist movement. The North began to view itself as the vanguard of the culmination of the American ideology of egalitarianism and modernity. Meanwhile in the South, the Anglo-Celtic, philosophically Christian establishment had changed little over the years since the founding of the South at Jamestown in 1607. Since the first Anglo-Saxons arrived in Dixie, they planted a tradition of landed gentry and high-church Protestantism that molded with the country, rather than revolutionized it, unlike the North, where industrialism, commercialism, mass immigration, and cosmopolitanism nearly exterminated the Puritan heritage of New England. Therefore, as proto-Marxism began to make its way into the mindset of Northern writers, artists, thinkers, and politicians, the clash over race and the question of racial equality was inevitable.

Though probably most Southerners were not fighting to protect the institution of slavery, as most Southerners did not own slaves, they were fighting to protect their land and heritage. But what was that heritage? The South was keenly aware of its Anglo-Celtic, Presbyterian way of life and did not want it tampered with by Northern Unitarianism, industrialism, and cosmopolitanism. Though the average Northerner or average Southerner was hardly thinking of the greater philosophical implications of the war, the elites of these respective sides definitely were. Whereas Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania was quite particular about wanting to bring up the black man at the expense of the white man, Vice President Alexander Stephens of the CSA most aptly expressed the views of the Southern intelligentsia when he said in his infamous “cornerstone” speech, “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man.”

Regardless of whatever policies were argued over through the war, the fundamental point was whether or not the previous lifestyle and age of Christian and white supremacy was to continue into the postbellum age. Obviously, with the North’s victory, egalitarianism began to reign at the expense of the American nation.

The power of this culture of white supremacy was still so powerful in the light of Lincoln’s egalitarianism, that it could not deter him from placing the Union on a higher plane than emancipation: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” Furthermore, Lincoln could not escape the temptation to send blacks back to Africa when in the 1850s he said, “If all earthly power were given to me . . . my first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia.” Now, Lincoln did move away from this position, not thinking it possible, but even so, it must be noted that the great emancipator, when pressed, preferred options of separation to integration.

Conclusion

It really makes one wonder: if the Founding Fathers espoused so much about equality and egalitarianism, why did they practice such un-egalitarian lives? And furthermore, if they were so concerned about the equality of all peoples, why did they leave behind no call for some sort of social justice and expansion of the franchise? The simple answer is that they did not believe in it. The ruling Anglo-Saxon aristocratic class cared little for expanding the rights and benefits of citizenship beyond themselves to other whites, let alone blacks or Indians.

To put it simply, the United States of the Founding Fathers has little in comparison with the contemporary United States. However, given the orthodox founding principles of America through her ancient patriarchs in the colonial era and through the founding era of the United States, ethnoreligious nationalists have the mandate to authoritatively declare: “America is ours.”

With its founding principles resting on religious authoritarianism and Caucasian supremacy, America is a white Christian nation. So long as we on the right never abandon this ancient identity and do not attempt to ignore or betray it, we provide a coherent and honest message to awaken and organize whites in America.

Rather than following the libertarian mantra that the Founders were fighting simply for liberty, we should instead support the Founders’ original vision: that America was destined to be an aristocratic, white Christian Republic. This will make the history and consequently the mandated mission of America to become much clearer and more honest.

America is currently wallowing in a depravity which is only worsening, amplified by the spiritual and metaphysical emptiness that curses every citizen in the nation. If white nationalists begin to own up to the honest history of the United States and our American civilization at large, whites will be able to provide a clear, messianic vision for their race in America and provide for them the needed energy to resist Hispanicization and Zionism.

| Tweet |

|

|

|