A bastard shall not enter into the congregation of the Lord; even to his tenth generation shall he not enter into the congregation of the Lord. – Deuteronomy 23:2

In his recent article on Rahab, Ehud Would provided us with grounds to see the mamzer-prohibition in Deuteronomy 23:2—the prohibition of “bastards” from the assembly of the Lord—to have mongrels as its principal referent, not those born outside of wedlock. Historically our English word “bastard,” even if it might solely refer to illegitimate offspring in modern parlance, was intertwined with debasement and adulteration, that is, unlawful mixing, before evolving to denote illegitimacy foremost. This is precisely the meaning of the term “bastardize,” which naturally has synonyms like “corrupt” and “adulterate.” Moreover, “bastard’s” etymological progression to refer solely to illegitimate propagation finds an analogue in the semantic scope of “adultery,” which itself perspicuously referred to adulteration but later came to indicate extramarital sex.

Besides these lingual evidences, I seek to supply additional commentary evincing that Deuteronomy 23:2 should be construed as a powerful prohibition upon mongrelization, and thus against miscegenation.

The Argument

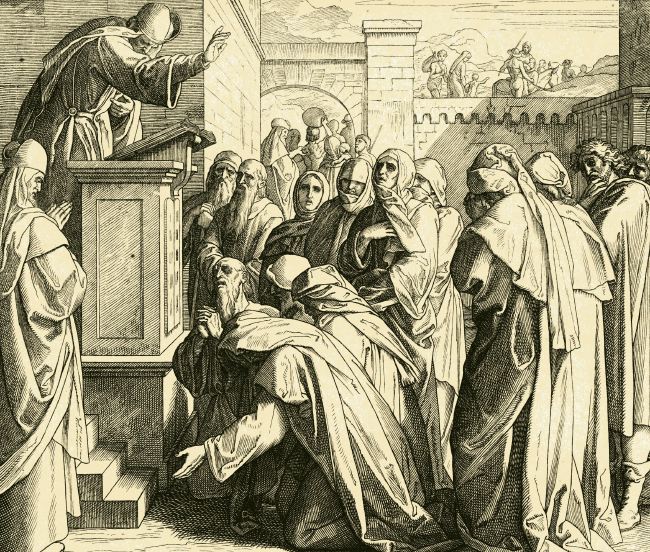

My central argument relates to the passage also cited by Ehud in his excellent article: Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s reforms in separating the mixed multitude from Israel. In Nehemiah 13:1-2, Nehemiah cites Deuteronomy 23:3-5:

1On that day they read in the book of Moses in the audience of the people; and therein was found written, that the Ammonite and the Moabite should not come into the congregation of God for ever;

2Because they met not the children of Israel with bread and with water, but hired Balaam against them, that he should curse them: howbeit our God turned the curse into a blessing.

The immediate response to this proclamation of the law is the separation from Israel of all the mixed multitude (v. 3). Just as alienists are gleeful to remark that the mixed multitude which departed from Egypt alongside Israel (Ex. 12:38) was composed of foreigners, so also it is clear that this refers to “all those of foreign descent,” as the ESV and other translations specify. Yet though the cited law excluded from Israel only Ammonites and Moabites, we know that other foreigners were present as well, for Ashdodite (Philistine) women also intermarried with Israelites (Neh. 13:23), and it would be safe to assume that some other nations found representation there as well, albeit in smaller proportions. The relevant feature of this narrative is the application of the cited Deuteronomic law to nations for which intermarriage was not specifically forbidden.

Ezra presents us with a similar, though historically earlier, situation. In Ezra 9:1-2, Israelite leaders report of intermarriage with foreign pagan nations, echoing the language of Deuteronomy 7:1-3, and Ezra similarly uses such language in his own penitential prayer to God in verse 12 of the same chapter. In Ezra’s prayer, the phrase “never seek their peace or their prosperity” (v. 12) is lifted from Deuteronomy 23:6, but otherwise the legal principles undergirding his reforms seem to stem from the explicit prohibitions on intermarriage with Canaanite nations in Deuteronomy 7:1ff.

Yet as with the presence of Ashdodite women in Nehemiah 13, here we have another interesting detail. Five of the nations mentioned in Ezra 9:1 are also cited in Deuteronomy 7:3 (Canaanites, Hittites, Perizzites, Jebusites, and Amorites), but of the other three nations with whom Israel intermingled, two are prohibited in Deuteronomy 23 (Ammonites and Moabites), and the other is not prohibited anywhere in the Law (Egyptians).1 Thus the book of Ezra presents us with certain connections between Deuteronomy 7 and Deuteronomy 23, the operative legal principles of which extend beyond the specifically enumerated nations to prohibit intermarriage with other foreign nations. The same is true for Nehemiah, who applied the general legal principle present in Deuteronomy 23 to annul the marriages which Israelites had formed with certain foreigners whose nation was not specifically prohibited in the Law.

This leads us to the central argument I wish to present in identifying the mamzer of Deuteronomy 23 as a mongrel: Ezra and Nehemiah would otherwise have had no legal basis for the application of their reforms. They both draw from Deuteronomic legal principles in applying the intermarriage-prohibition to nations not specifically prohibited in Deuteronomy (or anywhere else), but this entails that they were operating from some broader legal principle extending beyond the nations already explicitly excluded. Both Ezra and Nehemiah understood the Law to forbid intermarriage with certain foreign nations not specified in the Law, and they both articulated their reforms with reference to Deuteronomy 23: Ezra lifts some language from the passage and mentions the nations explicitly forbidden therein, while Nehemiah cites the passage directly.

Consider the severity of their reforms to understand more deeply the necessity of a firm legal basis underlying them. These were not simply rebukes at men for taking foreign wives, followed by affirmations of their abiding marital-covenantal duties; these were not reproaches for marriages validly-though-sinfully formed. Rather, these were annulments of marriages, declarations and recognitions that these were marriages falsely so called, as from their inception they lacked the support of the Law. The book of Ezra explicitly attests to the expulsion of the foreign children as well (10:3, 11). Such harsh and ironclad reforms would have been grievously sinful if applied to nations not certainly under any legal ban. Yet Ezra and Nehemiah are content with applying a broader element of these Deuteronomic statutes to nations not enumerated therein, knowing that the guilty Israelites were likewise cognizant of the verboten status of their unions.

Of course, it is one thing to note that Ezra and Nehemiah applied a broader legal principle to annul intermarriages with nations not specified in the Law, and it is another to assert that this legal principle is proclaimed in Deuteronomy 23:2 as a prohibition on all mongrelization. It could be that the legal principle by which Ezra and Nehemiah expelled the mixed multitude is not the principle specified in Deuteronomy 23:2. (That being said, this would still create a separate argument for kinism: if Ezra and Nehemiah both utilized some broad legal principle outlawing foreign intermarriage beyond the nations enumerated in the Law, then whether we can identify the particular law they cite or not, by the very fact that they nullified foreign intermarriage in general, we know that such intermarriage is outlawed by some statute or another within the Law, which is proof enough. But I wish to specifically argue that this principle is present in Deuteronomy 23:2.) Hence my intention is that this section serve within a cumulative-case argument for translating mamzer as “mongrel.” Given (1) the linguistic evidence, (2) the usage of Deuteronomy 23 in Ezra and Nehemiah, and (3) Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s utilization of an extant legal principle to broadly ban foreign intermarriage beyond the specified nations, we have powerful grounds, cumulatively, to hold that Deuteronomy 23:2 prohibits mongrelization; of all the statutes contained within the Law from which Ezra and Nehemiah could have drawn to expel the foreigners in their time, the best (if not only) law would have to be Deuteronomy 23:2. This is the argument.

The Alienist Interpretation Refuted

Alienists would deny that Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s expulsions of Egyptian and Ashdodite women were motivated by any principle which discriminated on the basis of ancestry as such; instead, they would insist that this ultimately reduced to the religious affiliation of the foreigners in question. This is the best way their position could be articulated: Ezra and Nehemiah identified Ashdodites and Egyptians as sufficiently idolatrous peoples, so that, because of the idolatry of these peoples (but irrespective of their foreign ancestries as such), they extended the intermarriage prohibitions to these nations as well.2 They might hold that as the explicit purpose of the anti-intermarriage legislation in Deuteronomy 7 is the religious purity of the Israelite people (e.g. verse 4), Ezra and Nehemiah applied this law also to other nations steeped in idolatry, annulling those intermarriages as well. Hence the broader legal principle by which their reforms were executed had naught to do with ethnic concerns, and thus the two men’s reforms provide us with no supporting evidence for the “mongrel” translation of Deuteronomy 23:2. Per the alienist, the prohibition placed upon mamzerim in Deuteronomy 23 is frankly irrelevant to the broader authority exercised by Ezra and Nehemiah, since their wise reforms were motivated by considering the religious ends of the anti-intermarriage legislation in the first place. Hence the alienist could presume that mamzer denotes illegitimacy or incest, not mongrelization, without his definition being challenged by this consideration from Ezra and Nehemiah.3 Yet the problems with this interpretation are manifold:

1. First, the alienist lacks the positive support which he believes his alternative interpretation has. A law can have religious purposes without forbidding an act that discriminates only on the basis of religion. That is to say, a law can have religious ends without forbidding an action that, by its nature, involves idolatry as such. Consider if some law prohibited sodomy and fornication with the principal intent of furthering the cause of religion; the lawgiver understands that sexual sin tends to ensnare people with worldly concerns as they indulge their appetites, and hence he places severe penalties upon sodomites and fornicators. In this example, the forbidden act would not be, by its nature, an improper admixture with idolatry, yet the prohibition would still serve religious ends. It is the same with the intermarriage prohibitions in Deuteronomy and applied by Ezra and Nehemiah. Scripture candidly attests that a central purpose of these prohibitions was to keep Israel untainted by idolatry, yet it does not follow that the action which is prohibited is nothing else than religious admixture. The prohibited actions are intermarriages with foreigners, i.e. with other nations as nations. Thus the support which the alienist believes he has for his alternate interpretation is negligible. There is no positive reason to suppose that the principle by which Ezra and Nehemiah annulled intermarriages with Ashdodites and Egyptians was some general prohibition in the Law against marriages with preponderantly idolatrous peoples. The religious ends of the anti-miscegenation legislation fail to furnish evidence for such an interpretation.

2. Besides lacking positive evidence, the fact that Ezra and Nehemiah discussed this issue in terms of foreigners and nationalities shows that their reforms operated along ethnic-national lines as such. The fruit of Nehemiah’s reform was that Israel separated from “all those of foreign descent,” and (as Ehud showed) Ezra identifies the fundamental problem as intermarriage with allotrios peoples, that is, foreigners. But if Ezra and Nehemiah both cite legislation which forbids international marriages as such, and if they both decry the influx of foreigners, then simply from those preliminary considerations, we have great reason to believe their reforms were based upon ethnic distinctions as such, not religious distinctions, even though we happily cede that they viewed the foreigners as rampant idolaters.

3. Without supplying a specific statute in the Law that would have made all marriages with preponderantly idolatrous nations to be invalid, alienists must deny that Ezra and Nehemiah had any legal basis for their reforms. For there are two ways in which marital covenants can be invalid – not merely sinful, but entirely invalid: either by nature (e.g. in the case of two men or two women), or, even if they are valid by nature, by certain positive laws. We know from St. Paul (1 Cor. 7:12-14) that interreligious marriages are not invalid by nature, so we must appeal to relevant positive laws here. In this case, God delivered positive laws specifying the invalidity of Israelite marriages with certain nations, as everyone must admit;4 as a result, any putative marriages formed by Israelites with those nations would be invalid, and hence subject to annulment. But the problem for the alienist is explaining what positive-legal basis there is for the annulment of intermarriages with Ashdodites and Egyptians. Without citing a law like Deuteronomy 23:2, he cannot furnish such a positive law, and hence must conclude that Ezra and Nehemiah had no legal basis for their reforms.

It would be insufficient for the alienist to contend that the general equity of the anti-intermarriage laws could also have been extended by Ezra and Nehemiah to other preponderantly idolatrous nations. A law’s general equity refers to the moral principles (that is, the principles of natural law) undergirding specific positive legislation as those principles are applied to certain circumstances. Assuming the alienist take on this law’s general equity is correct – that the moral basis for the law is merely to prohibit intermarriage with preponderantly idolatrous nations, without regard to ethnicity as such – he could thus hold that a subsequent lawgiver, endowed with due authority, could have issued a new law prohibiting intermarriage with certain other nations not already enumerated in the Law, appealing to the general equity of the anti-intermarriage laws as his justification. But this is very different from holding that the Law which Ezra and Nehemiah applied already included such an extended prohibition. It would be unjust for Ezra and Nehemiah to figure that because the general equity of the Deuteronomic legislation could have been extended to forbid intermarriage with other idolatrous nations, therefore the Law actually was so extended. In fact the Law did not contain any specific statute generally forbidding intermarriage with preponderantly idolatrous nations (analogous to what kinists claim is forbidden by Deuteronomy 23:2), so without any such general law, the alienist would have to conclude that Ezra and Nehemiah lacked proper legal backing for their implementations. Ezra and Nehemiah were not new legislators, but appliers and enforcers of the extant Law to that point, and they righteously assumed that the intermarrying Israelites were culpably knowledgeable of the Law’s demands. Thus, without any existent law actually forbidding intermarriage with preponderantly idolatrous nations in general, their annulment of various intermarriages would have been terribly unjust.

This highlights the strength of the argument that mamzer must be translated as “mongrel,” for there is no other reasonable means by which Ezra and Nehemiah could have applied the Law to nations not explicitly forbidden therein. No alienist presumes to specify a law generally forbidding intermarriage with preponderantly idolatrous nations, so without a statute like Deuteronomy 23:2 to generally forbid intermarriage with foreigners, the reforms implemented by Ezra and Nehemiah would have been legally groundless.

Other Objections

Though without a suitable explanation for the annulment of Ashdodite and Egyptian intermarriages, the alienist might still object to the propriety of importing Deuteronomy 23:2 as the rationale for Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s correctives. Specifically, he could object that Deuteronomy 23:2, especially its key term mamzer, is not even present anywhere in either of the books. Given the absence of any explicit citation of this law, it would be improbable that it was operative underneath Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s reforms.

Importantly, however, other excerpts from that section of Deuteronomy 23 are mentioned with relation to the expulsion of the mixed multitude, as stated above. Ezra acknowledged intermingling with Ammonites and Moabites, he quoted from Deuteronomy 23:6 in his prayer to God (9:12), and Nehemiah 13:1-3 cites Deuteronomy 23:3-5 directly; more significantly, this latter citation occurred in the midst of the reading of the Book of Moses to the people (Neh. 13:1), in which case the mamzer prohibition would certainly have been read and understood as the context of the more specific prohibitions placed upon Ammonites and Moabites. This same qualification can be provided for Ezra’s case, as, in all likelihood, the reading of the Law likewise occurred in his time (for all reformation is predicated upon obedience to the Word of God), even though the book does not explicitly record it. And it would be foolish to suggest that Ezra did not have the legislation of Deuteronomy 23 in mind as he, a priest, considered the forbidden marriages contracted with Moabites and Ammonites.

Furthermore, in Ezra’s case, when we consider the interconnections of Scriptures as he first heard of the situation and prayed to God in repentance (primarily alternating between language from Deuteronomy 7:1-3 and Deuteronomy 23:3-6), and when we grasp the ordinariness of the principle encapsulated in Deuteronomy 23:2—these were not antiracist Israelites, after all—and when we contemplate the main (but not entire) application of these anti-intermarriage laws to nations explicitly forbidden in the Law, it is entirely fitting that the law prohibiting mamzerim would be contextually operative and in the minds of the relevant officials, even if not explicitly cited.

A separate alienist objection would be to back away from this entire discussion, look at the verse “a mamzer shall not enter into the congregation of the Lord,” and note how cryptic such a passage is. All sorts of commentaries express confusion as to the exact meaning of the phrase “enter into the congregation of the Lord”: is this a purely ecclesiastical privilege? A civil privilege? Both? Does it reflect only the privilege of attaining some sort of office, or does it apply to membership in the Israelite covenant community? Does it permit membership, but only in creating an even lower tier of member? If it denotes office-holding, what level of organization in particular? Tribal, or pan-Israel?

I concede the difficulty of knowing exactly what this phrase means from the context, or why this phrase was selected to denote whatever it precisely means. But with the inspired application of this law by Ezra and Nehemiah, and the inspired commentary attesting to the righteousness of their application, we know, at the very least, that it is related to rights of intermarriage. At minimum, restricting Ammonites and Moabites from entering into the assembly of the Lord directly entailed the invalidity of any intermarriages formed with them. Thus, assuming that “entering into the congregation of the Lord” carries the same meaning when applied to other subjects in Deuteronomy 23:1-8, we can infer that such a right does not refer to the right to hold office, but to something more basic at the level of private citizens. Yet whatever else we can infer about such a right of entrance, we know that the mamzer is restricted from the right of intermarriage in the same way that Ammonites and Moabites were. Admittedly, this is a different claim from forbidding any individuals whose union with an Israelite would produce a mamzer from intermarrying, but that is a sufficiently straightforward legal implication from the mamzer-prohibition itself. Thus, even if we must remain agnostic concerning the exact details of “entering into the congregation of the Lord,” we can assert from the analogia fidei that these marital implications are clear, though amid obscure details. This objection then returns us back to the definition of mamzer as the sole issue at hand.

A third alienist objection would challenge the definition of mamzer as “mongrel” due to the dearth of commentaries historically supporting such a view. For example, though Matthew Poole,5 Matthew Henry, John Gill, John Calvin, Adam Clarke, and Keil and Delitzsch all have varying interpretations, they all generally stress incest, fornication, or adultery for the classification of mamzerim. The only countenancing provided for the mongrel interpretation comes from Gill and Poole: Gill notes in passing that “some think such only are intended who were born of strangers and not Israelites.” Poole holds that mamzer refers to the offspring of “any prohibited mixtures of man and woman” as a catch-all, and later states, “But some add, that the Hebrew word mamzer signifies not every bastard, but a bastard born of any strange woman, as the word may seem to intimate.” So Poole provides a small nod to the mongrel view, postulating that illegitimate mongrels might be in view, according to the nature of the term mamzer. Yet overall, the mongrel interpretation receives little support from these (and likely other) commentators.

While one should disagree with historical commentators only with great humility and hesitancy, and while the burden of proof should be placed upon the novel position, nevertheless older, established positions are still fallible and surmountable. In this case, we have an unclear term in an obscure passage that has not been illumined through fiery, focused debate earlier in church history (as, say, Romans 5:12 was in debates on original sin). Generally these Christian commentators relied for their views upon the Talmudist consensus, which is in many ways unreliable, and though they did not unanimously present the mongrel interpretation as a prominent option, they did not unanimously (or singularly) discredit it either, nor did they unanimously support any particular non-mongrel interpretation, nor did any of them confidently assert his own interpretation as the best, nor did any seek to provide unwavering evidence for his particular interpretation, since they evidently did not see the proper interpretation of the term as that systematically crucial. Hence, given the minor weight we, with due diffidence, can impute to these historical commentaries, thus reducing the evidential bar required of our newer position, and given the minor weight attributed to a mongrel interpretation by Gill and Poole, and given the linguistic and exegetical evidence we can provide, we can also resist this final alienist objection, even as we acknowledge it to be the best one.

Possible Evidence Against Alternate Definitions

Matthew Poole provides intriguing commentary upon the definition of mamzer which could bolster the evidential case for the mongrel definition. As an objection to a definition of mamzer as one born of either incest or fornication, he cites both Pharez (Perez) and Jephthah.6 Pharez was one of the twins born of Tamar’s deceptive and incestuous harlotry with Judah (Gen. 38:29) and a forebear of the Messiah (Matthew 1:3), whose great-great-grandson Nahshon (1 Chron. 2:4-10) led and commanded the Judahites (Num. 2:3; 10:14), whereas Jephthah was a harlot’s son (Judges 11:1) who nevertheless rose to political prominence in Israel (Judges 11:11). As Deuteronomy 23:2 forbids any descendant of a mamzer from entering into the congregation of the Lord—and this was truly an eternal ban, not a literal ten generations, as Nehemiah 13:1 attests—if a mamzer were a child of either fornication or incest, then Jesus, via his Pharezite ancestry, would be thereby excluded from Israel and utterly unfit to rule them as one of their own (Deut. 17:15). Nahshon would be likewise excluded. Further, as Jephthah was born of a harlot who is identified as neither a second wife nor a concubine of his father Gilead, and as his legitimate half-brothers utterly shunned him as a stranger (Judges 11:2), he was in all likelihood illegitimate, in which case he ought to have been separated from Israel, certainly barred from high office. But the prohibition on mamzerim is not even mentioned by the “elders of Gilead,” the same ones who were aware of Jephthah’s ancestry and who hated him and shunned him on that account, as a hindrance to his ascension. The conclusion to be drawn from these two examples, allegedly, is that the mamzer of Deuteronomy 23 cannot be identified with children born either of incest or of fornication, overthrowing two of the most prominent interpretations. This leaves adultery and especially miscegenation as the two legitimate candidates, substantially increasing the probability that Deuteronomy 23:2 does indeed outlaw mongrelization.

Poole offers these arguments only hypothetically, however, as he then responds to them. First, he says, “God gives laws to us, and not to himself; and therefore he might, when he saw fit, confer what favour or power he pleased upon any such person, as he did to these.” Second, he cites as possible the aforementioned interpretation that a mamzer is not just any bastard, but a bastard born of a foreign woman.

Both these arguments are poor. The combination bastard-mongrel interpretation of mamzerim would truly address the examples, yet we are much more justified in accepting the mongrel interpretation over this bastard-mongrel reading; and even if we accepted the bastard-mongrel reading, the moral and civil implications to be drawn from such a prohibition would lead toward kinism anyway. His first response is a commonly-cited argument – especially among attempts to harmonize the ancestries of Rahab and Ruth with biblical prohibitions against Canaanites and Moabites – but it does not apply. It is true, of course, that God is above His own law, but the relevant implications are limited to these two facts: God can Himself perform an act despite forbidding others to perform that same act, and man can contravene a divine law only if God first rescinds that law for him. Yet neither of these two facts applies to Pharez and Jephthah. In Jephthah’s case, the Gileadite elders elevated him to a high political position despite knowing of, and shunning him for, his status as a bastard. The text reports no divine revelation to those elders communicating that the prohibition on mamzerim was temporarily lifted for Jephthah, nor could we suppose that any favor for Jephthah which God may have supernaturally implanted in the elders’ minds would constitute such a clearly revealed rescission of Deuteronomy 23:2. In the absence of such knowledge of the law’s rescission, they would not be legally permitted to violate such a law. Pharez’s case is similar for Nahshon, but it is otherwise dissimilar, since Jesus’s divinity would permit Him to act contrary to Deuteronomy 23:2 as He wished. Yet in Pharez’s case, there are two countervailing considerations: first, the remainder of Christ’s mission showed His willingness to identify Himself with His people entirely, that He might be our suitable and perfect representative. It would be unfitting for Him to have emphasized to the Pharisees His perfect conformity with the Law of Moses in all points, only to then, at this point alone, assert His divine prerogative not to follow the Law which He commanded Israel to follow. Second, and more clearly, independent of Jesus’s claims to citizenship and kingship based on His lineage, clearly all of Jesus’s forebears, all the other descendants of Pharez prior to Christ, would have been excluded from Israel, including Nahshon, and especially including whichever of his fathers was present at the time of Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s reforms. Yet the absence of any such protestations against Boaz, Jesse, David, Solomon, and many other crucial ancestors of Christ is sufficient proof that none were considered to be barred from citizenship (and particularly from the throne) by their descent from a mamzer.

All that said, arguments could still be forged against these two examples. One could argue that the repeated mentioning of Jephthah’s bastardy in Judges 11 is just another evidence of the Israelites’ rebellion against God in the days of the judges: despite first ostracizing Jephthah for his illegitimacy, they were willing to contradict their previous sentiments and ignore God’s law in order to fight the Ammonites. Given the negative light which Scripture casts on their ostracism of Jephthah, and given that they could have offered Jephthah a number of other incentives besides political power, I hold this interpretation as erroneous, but it is worth mentioning as a possible alternative.

More importantly, the objector could cite Shelah, a separate son of Judah, as a counterexample to our argumentation. According to Genesis 38:2-5 and 1 Chronicles 2:3, Shelah was born of Shua the Canaanitess, and according to 1 Chronicles 4:21-23, Shelah and his descendants evidently had vocations within Israel, residing there and most likely intermarrying without molestation. Given the classification of children from Israelite-Canaanite intermarriages as mongrels, if our interpretation of mamzer is correct, then this entire mongrel line would have been barred from citizenship and intermarriage with Israel. Yet we find the opposite is the case. On this basis, the alienist could argue that whatever answer we provide to reconcile the Shelahites with our mamzer interpretation, they could do the same for the Pharezites with theirs, and so their mamzer interpretation would be undisturbed by such an example. With this tu quoque objection in mind, I will proceed to explain how kinists might understand the Shelahites in light of the mongrel interpretation of mamzer.

The most relevant fact concerning Shelah is that his birth occurred prior to the giving of the Law, prior to the specific prohibitions placed upon Canaanite intermarriage and upon all mamzerim. Some might see this as a completely sufficient reason to dismiss both Shelah and Pharez as relevant to the interpretation of mamzer, but this is not the conclusion of our explanation. Applying such legislation to Shelahites and Pharezites cannot simply be written off as ex post facto, for the simple fact that the legislation in question is applied to certain types of individuals, certain descendants, rather than to criminal acts. Deuteronomy 23 states not that those guilty of committing such-and-such an act will be punished accordingly, but that those of such-and-such an ancestry are not permitted entrance into the congregation of the Lord. The prohibitions on Ammonites and Moabites were operative for all with Ammonite and Moabite ancestry at the time of the legislation’s issuance, not merely for all Ammonites and Moabites who would be born subsequent to the giving of the Law. Similarly, whatever the proper interpretation of mamzer is, the straightforward import of the law is that all those classified as mamzerim were, at that point, barred from the congregation of the Lord.

The solution to this involves an “ex-ante qualification” to the law, that is, some respect in which the law did not operate purely “retroactively” in applying to all those whose ancestries were enumerated by the law, but treated cases differently for actions performed prior to the law. For example, we already know per Nehemiah that Deuteronomy 23:3-5 forbade Ammonite and Moabite intermarriages from being formed, but suppose that at the time of that law’s issuance, an Israelite man was already married to a Moabite woman. It would have been supremely unjust to, then and there, annul his previously lawful marriage and disenfranchise his posterity, especially given that the prohibition on Moabites was despite their close blood-ties with Israel. Annulling an intermarriage with a nation of blood-kinship, prior to that nation having officially forfeited its right of integration with Israel, would be monstrously inequitable. Hence we would suppose that, though it is unwritten in the text, the Israelites understood an ex-ante qualification to exist for Israelite-Moabite marriages at the time of the law, if there were any. But if we can surmise that such an ex-ante legal qualification would have arisen in Israel, despite the text not specifically outlining these qualifications, then that category is generally open to us in harmonizing these texts. We can hold that while the Shelahites may have had some measure of Canaanite blood, the admixture of Canaanite stock prior to the Law would have been sufficient, given an equitable ex-ante qualification of the law prohibiting mamzerim, to still permit their civic rights and residence in Israel. (A completely alternate answer would be that Shua, though described as a Canaanitess, was not so ethnically distinct from Judah as to classify their offspring as mongrels, in which case the mamzer prohibition is not even relevant to Shelah, only the specific commandments not to intermarry with Canaanites in particular—which forbade particular acts of intermarriage, not persons of Canaanite ancestry as such. But we can discard this hypothesis as too speculative.)7

The alienist who supports an incest- or fornication-based definition of mamzer could then appeal to a similar ex-ante qualification in order to reconcile his mamzer interpretation with the Pharezites, but there is a reason to believe that an ex-ante qualification would not be appropriate in such cases. Fundamentally, any laws governing intermarriage naturally will have certain ex-ante exceptions in order for the legislation to equitably countenance intermarriages that exist at the point of the legislation’s issuance; this is why in the first place we could hypothesize, merely from the example of the Ammonites and the Moabites, that ex-ante qualifications are reasonable to postulate. But incest and fornication do not, by their nature, seem to require any ex-ante qualifications in order for laws disenfranchising the children born from such acts to be equitably treated. If new inheritance legislation were passed declaring that only trueborn children could inherit their father’s estate, then the immediate application of that law to bar bastards from inheriting would not be an unjust application requiring the law to have some sort of ex-ante qualification. The same goes for incest. But if neither incest nor fornication would seemingly require an equitable law to have such ex-ante qualifications built into it, then alienists cannot appeal to the mere possibility of ex-ante qualifications in order to harmonize their mamzer interpretation with the Pharezites, whereas kinists can legitimately make such an appeal to harmonize their mamzer interpretation with the Shelahites.

That said, forbidding all ex-ante qualifications to the alienist is not an open-and-shut case; it depends on the reasonability of applying such qualifications to intermarriage laws as opposed to applying them to incest- and fornication-based laws. So, as with the last-ditch argument that could be forged against the example of Jephthah to salvage a fornication-based interpretation of mamzer, I also would ultimately find the alienist explanation here to be erroneous even while I admit that, as a possible alternative, it weakens the kinist case to some extent, and does not permit Pharez to be cited as an irrefragable, silver-bullet counter-example to an incest- or fornication-based definition of mamzer.

As a separate observation to conclude this section, it also would be fitting here to oppose the alienist contention, independent of the foregoing argumentation, that Shelah’s Canaanite admixture rolls into a typical alienist “we’re all mutts” argument, which whites of varying Northern European stocks love to make. Let it be known that if a slight admixture of Canaanite blood into Israel should lead us to deny the reality of ethnic and racial boundaries (of which Loki would approve), then it would also have undercut the definite national distinctions presupposed in Israel’s own legislation, thereby undermining divine revelation itself.

Conclusion

The definition of mamzer as “mongrel” is supported not merely by linguistic evidences but also by supplementary exegetical arguments. If the Deuteronomic law contained no wide and general prohibition on mongrelization, then the reformers Ezra and Nehemiah would have lacked a legal basis for applying their reforms to nations not enumerated in the Law itself. The best alienist alternative to this interpretation has various faults, leaving the mongrel interpretation of Deuteronomy 23:2 as the most legitimate interpretation. Furthermore, we can look to the examples of Pharez and Jephthah as counterexamples to fornication- and incest-based definitions of mamzer; even while alienists could offer certain mitigating factors related to these examples, in sum the more reasonable view is to see both examples as disproofs of those two non-mongrel definitions for mamzer. When we consider all the relevant evidences in total, and banish all impinging “antiracist” prejudices for the unscriptural follies that they are, the superior position to hold is that the mamzer of Deuteronomy 23:2 is indeed a mongrel, vindicating a Christian racialist worldview.

Footnotes

- On the contrary, Egyptians in some sense were granted rights of assimilation into Israel, according to Deuteronomy 23:7-8. The resolution to this would be either that Deuteronomy 23 is referring to different Egyptians than Ezra 9, for Hyksos and other Semites could be classified as Egyptians, and Deuteronomy 23 describes the Egyptians as kind hosts, which evidently is not describing the subset of those called Egyptians who brutally enslaved the Israelites; and/or that the three-generation requirement put on Egyptian immigrants (Deut. 23:8) was violated in their immediate intermarriages with Israelites. Neither of these solutions would provide solace for the alienist, however. ↩

- Note: this is different from the absurd alienist interpretation that Ezra and Nehemiah sought merely to prohibit interreligious marriages, they having no issue with international unions between two believers. Such an interpretation is manifestly refuted by the text. (And such an interpretation is not required for alienists, either. The more sophisticated alienist could hold that while the intermarriage prohibitions are placed upon nations as such, the intent of the prohibitions is to avoid the preponderant, but not universal, idolatry of those nations; in other words, because certain foreign nations are idolatrous for the most part, therefore it is fitting to make a positive law prohibiting all intermarriage with such nations, even though some such intermarriages could be between two believers.) The particular interpretation here is that the legal principle by which Ezra and Nehemiah annulled intermarriages with nations not specified in the Law was based on their identification of preponderantly idolatrous nations; they identified these nations and annulled all intermarriages with them. ↩

- If this alienist interpretation is reasonable to hold, then such a definition of mamzer could still be challenged by other evidences (mostly linguistic), but not challenged specifically by citing Ezra and Nehemiah. ↩

- I would hold that these positive laws were delivered as civil positive laws for Israel (i.e. by God for the sake of Israel’s civil government), not strictly as divine positive laws, such that the general equity of these laws permits modern states to also enact anti-miscegenation legislation. But such a debate is not germane to the topic at hand. ↩

- Annotations Upon the Holy Bible, Volume 1, p. 380. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Moreover, even if this alternate explanation is true, the alienist would not be cut off from appealing to an ex-ante qualification in the law when explaining the Pharezites, for we already can surmise such an ex-ante qualification to have applied to Moabites and Ammonites, regardless of whether it applied to the Shelahites. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|