Part 1

Another such crisis of conscience came before long when the churchmen prescribed memory verses to the Sunday school class. The facilitators told us that it was a test of faith. If we had true faith, the Holy Spirit would empower us to memorize the lines perfectly. I do not recall the verse given me, but I remember it was three or four sentences long. I failed to recite it accurately by the end of class and was informed by a woman facilitator again, but more sorrowfully, that my inability to memorize said verse proved that I did not have the Holy Spirit. I was not yet a Christian. This episode shook me as well. Again I returned to the pages of Scripture. I could find nothing about such a test of salvation as described by my teachers. Slowly, the anxiety of that false teaching subsided as well, and was yet again replaced by greater faith in Christ as my only hope – a hope that transcended my own understanding.

But my faith may have been reinforced as much, or more, by what came after church: every Sunday I made it home just in time to watch Tom Hatten’s Family Film Festival with my grandparents. Therein was I introduced to classic cinema from an age when the Christian West held to a more confident vision of itself and the world. We talked about Sunday school and those old films over apple or cherry pie which on Sundays my grandmother always had on hand.

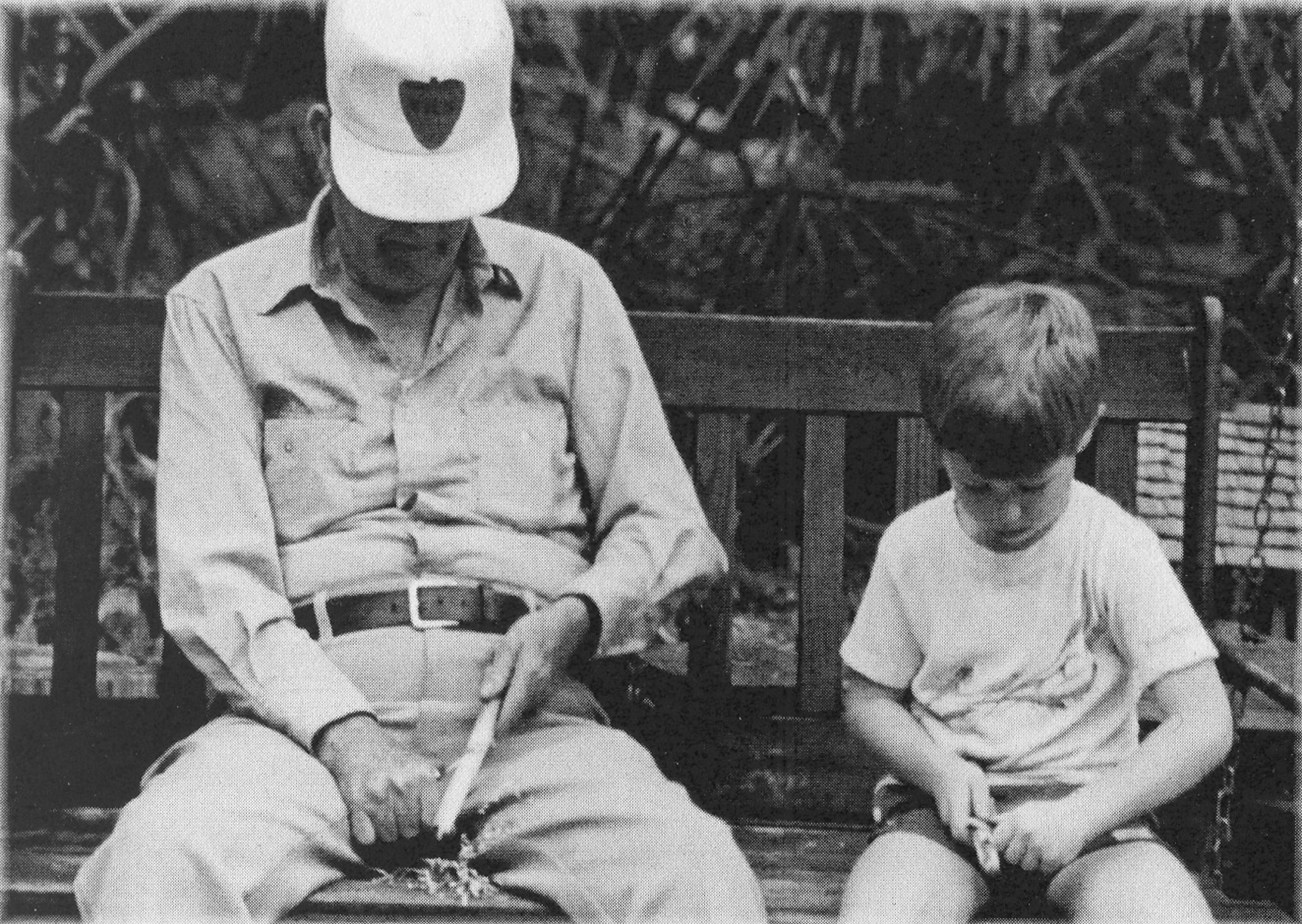

My Paramount home throughout these years, short though they were, remains in my memory my true childhood home. It was a large house on a big plot (at least for the area) which took up roughly a third of the block. The rear of the property was covered with a thicket of trees that never failed to fire my imagination. We had apricot, grapefruit, orange, lemon, passionfruit, and mulberries growing wild all about the property, and my Poppa planted a respectable vegetable garden with me, the produce of which we often traded with the old miser across the street for the avocados he grew.

As I said, the neighborhood was mostly White when we moved in. Our block, entirely so. But one day when my sister had been down on the next block riding her bike with a friend, she ran into trouble. Two young Black boys came out of nowhere and tried to knock her off her bike, but she kicked them off her and pedaled home as fast as she could. And they gave chase. I don’t recall what I was doing, but I heard her screaming for me as she came riding up into our yard. And sure enough, the two Black boys came running up close behind her. The smaller one was the more aggressive of the two, so I flew into him, knocking him backward. But they were both on me in an instant. And the fight lasted only a few moments before Poppa came out with his belt in hand and my dog Buck (a German Shepherd/Black Lab mix) at his side. The Black kids were terrified of both. What with Buck’s snarling, Poppa only had to lay a couple stripes across their backs before they turned heel and ran back the way they’d come. Buck chased them down the drive nipping at their ankles as they went. They cursed us in terms unknown to me. But they didn’t come back.

The next day Poppa had me start training with him. At eight years old I couldn’t hope to do all the one-armed pushups, finger pushups, or handstand pushups that he did, but he was determined to toughen me up. He said, “Niggers got every bit as much right to live as you do. God made them what they are and you can’t hold that against them, but if they lay hands on your sister, by God, you kill ‘em.”

Later that year a Mexican family moved in next door. Their oldest boy, who was my age, started slapping my little cousin Nikki (my aunt and uncle had moved in around the corner) around for fun. When I heard of it I went straight over to tell him to leave her alone, all my little cousins and my sister trailing along behind me. But reaching his house we saw he had company – two other Mexican boys, also about my age. All I said was, “Please quit hitting my little cousin. She’s not even five.” To which they all took turns replying that they’d hit her anytime they wanted and that they might shoot her. This scenario immediately bridged over in my mind to the indignity of my sister’s attack earlier that year. As the Mexican boys’ words still hung in the air, I punched the main offender in the solar plexus (as Poppa had taught me) as hard as I could, leveling him to the ground. There he lay, gasping for breath. The paramedics were even called and they took him to the hospital to be checked out.

All of this pleased my grandfather greatly. He congratulated me on being a man. But my mother was another story. She was appalled at what I had done and that Poppa had trained me to it. That argument went on a long time. The only word I remember from their exchange, on account of its repetition, was “racist.” But I think he sensed the conflict which my mother’s outrage had seeded in me. The next day Poppa reassured me I’d done right protecting my cousin, rewarding me with my first pocketknife. I cherished that knife.

Though my classes were all in English now, the liberal agenda was sailing full mast there as much as at my previous school. I remember little of the actual curriculum other than the fact that in my third grade year, only one year after my having taught myself to read phonetically, they introduced “Whole Language Reading,” otherwise known as “Sight Reading,” patterned in theory after the Oriental system. This was, of course, totally incompatible with the English language, but that wasn’t why I ignored the new approach. I did so because I had already learned to read phonetically, and no matter how much the teachers tried to undo that foundation, I could not stop seeing the letters as sounds. And in retrospect, I attribute my winning second place in the Los Angeles County Spelling Bee in fifth grade to the fact that I clung to phonetic language, in spite of all instruction to the contrary.

I only had three field trips in the course of my school career (I’m told this is an unusually low number). One was to the natural history museum where evolution was the thrust. Another was to San Juan Capistrano Mission which should have been the perfect springboard for discussion of Christian missions in America, Westward expansionism, etc., but instead was used to push the political theory of Aztlan. The last one was a trip to Oliveria Street in Downtown L.A. The point of which, again, was the political doctrine of Aztlan. The docent even referred to Mexicans as “the golden race.”

I took part in two stage productions in elementary school. One was a Mexican hat dance in which I wore a sombrero and serape and sang a Spanish song the translation of which I never learned. Even at age eight I felt rather humiliated by that bit of Mexican Kabuki. The other event was my fifth grade graduation ceremony in which the entire class sang that multicult globalist anthem, “We Are the World.”

The staff were perfectly selected for such social programming: out of four years at that school, only one of my teachers was straight. Two were sodomites, one was a lesbian, and the sole heterosexual woman was an emotional wreck. Albeit she may have had good reason in that environment.

Another aspect of the social landscape which was impossible to ignore was the developmental disparities between the races there. Most of the ten-year-old Mexican boys had already begun growing mustaches. A few even had sparse beards. Many of the Black boys at that point were over six feet tall. And all the girls of those races had by that age already developed breasts – some as early as first grade. Meanwhile, most of the White kids wouldn’t hit puberty for another three or four years.

The rapid development of the non-White children paralleled the neighborhood’s accelerated process of transformation. In the course of six years it would go from almost entirely White to almost entirely non-White. Poppa and all the White men who frequented the corner barber shop in town were of one mind on the subject: they agreed that this transformation was expedited by the eminent domain seizure of a trans-county corridor of land in the 1950s. Hundreds of blocks of houses had been left unoccupied for three decades to make way for the eventual construction of the 105 freeway; the land lay fallow and had been retaken by the forest. I don’t know where we got it but we kids had an ominous moniker for it – Darkenwood. The houses of Darkenwood had long been inhabited by homeless hippies and bohemian types, all of whom had been regarded as more or less harmless, but they were being driven out of those free woodland homes by hyper-violent illegal aliens from Mexico. That freeway-slated swath of land was acting as a path of least resistance for the browning of the surrounding area. The more violent Mexicans settled in that channel, the more White homeowners pulled up stakes to move away from the town. Whether they sold or rented the property out, the results were the same: values plummeted. And who would flood in at cut-rate pricing? Blacks and Browns, of course. So it was that the Rand Corporation came to rank our city, on myriad social indices, as the fourh worst city in America. Though no disaster in the usual sense had occurred, Paramount was declared a disaster area by the federal government.

The summer straddling my fourth and fifth grade years was eventful. I was sent north by my mother to work on my paternal grandmother’s farm in the San Joaquin valley, the breadbasket of California. The town of Porterville carries the eternal distinction of having been the last recognized horizon of the Western frontier. In the year of my first furlough there, 1987, there were yet many living who had arrived in Conestoga wagons as children. I met many settler descendants who had managed to resist modernism to the extent that they still lit their homes exclusively by kerosene and oil lamps, and lived their lives on horseback. And I met two old ladies of settler stock who were proud to have never ridden in an automobile, nor eaten in a restaurant. The nearby Indian tribes had some political clout, but the Mexican population at the time was sparse and seasonally dictated by way of the fact that they were all field hands. Otherwise, Porterville and the surrounding areas were populated by decidedly conservative White Protestant folk. But my family’s situation there was a bit different.

My paternal grandmother was Danish out of Council Bluffs, Iowa. Though of a conservative Lutheran family, she married a Scots-Irish Presbyterian. After birthing four sons by him, for reasons never divulged to me, they divorced. She would marry and divorce twice more before taking up at last with, of all things, a Mexican convict who spent twenty years in prison for having beaten a Black man to death in mutual combat. Due to his explosive temper, those twenty years were mostly spent in solitary confinement. He was perhaps the most volatile person I’ve ever met.

Only adding to the shame, as my grandmother explain it, she married him to snub her prim Danish family. At age eleven it was all very strange to me. All I knew was that the man was a monster who threatened and/or physically assaulted people everywhere he went. And I was placed for a season under his stewardship.

He delegated to me the daily feeding and upkeep of hogs, chickens, and rabbits as well as all slaughtering of the same. If I’m grateful for the farm experience, I would not wish the stewardship of such a man on my worst enemy. Mixed blessings, indeed.

But in school I did have a close Mexican friend. At least for a time. We had lots of foot races and boxing matches. We beat each other bloody and, at least for my part, genuinely enjoyed it without animosity. At some point he invited me to join him at the Paramount swap meet on Saturday. He said he made money there every weekend loading and unloading merchandise for the vendors. My inner entrepreneur lept at the suggestion, so on Saturday we met at the swap meet before dawn. I had never been there before and had no idea what I was getting into. I was the only White face in a sea of Brown, and aside from my friend Jose, I was the only kid.

Jose was taken on by a carpet salesman within ten minutes of our arrival, leaving me to wander the bazaar alone. I cheerfully persisted for the next two hours, offering my services at length to every vendor at the event, but without success.

When Jose found me he said he made twenty bucks. Not bad pay for two hours of a kid’s life in the 80s. But when he asked how much I made, I told him no one would hire me. To which he responded with disgust, reminding me that he picked up work there every weekend. It dawned on me immediately that the determining factor in his success and my failure in that venue was ethnic nepotism: he was hired an account of being of similar makeup to the vendors, and I was overlooked for being a gringo. Nonetheless, I went on to try again every Saturday for the next couple months with no better results than at the first. In the end I didn’t begrudge their ethnic nepotism, but Jose seemed to resent my making it apparent. He quit hanging around with me after that.

Entering junior high school, I noticed immediately that the ratio of White to non-White had tipped radically toward the latter. If my elementary school was 35% White, my junior high was probably 5%. By this point the daily walk to and from school had become a harrowing experience. Along the path home each day I was, at minimum, cursed at from passing cars. Having things thrown from those vehicles was also common. Occasionally someone would pull up quick onto the curb and jump out with tire irons, wrenches, bottles, knives, etc. to assault you. These things were as often done by adults as teenagers. Hard as it is to believe, it all became a normal part of life for the few remaining White kids there.

Read Part 3

| Tweet |

|

|

|