I was thirteen years old. The place, Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, CA.

By happenstance, my friends and I had chosen to go to the amusement park on a night on which the Jim Rose Circus was performing there, but I had never heard of them before that night. Now, I had by that time seen enough folks with jailhouse tattoos and guys with left ears pierced in pirate fashion, but those practices were then still confined to very specific corners of society: bikers, skaters, gangbangers, punk rockers, sailors, ex-cons, and drug addicts, mostly. Beyond that, tattoos and the broader category of which they are part – Body Modification (Bod-Mod) – were still extremely rare. So rare that we had no popular reference to terms like “scarification” outside anthropology texts on New Guinean cannibals, let alone hep terms like Bod-Mod. It’s hard to believe now, but on that summer night in 1990 when the inked, scarred, and pierced Jim Rose performers took the stage the audience of a thousand or more people let out audible gasps. Most people had really never seen full sleeve and facial tattoos before. Even the occasional Mexican jailhouse thug one encountered then would only have a smattering of sloppy script, chola faces on his back, or a teardrop or two under one eye; but these folks had tiger stripes and jigsaw patterns scrawled on their faces and their bodies were a patchwork of ink, scars, metal rings and rivets. Folks standing around me on all sides began whispering to their neighbors, “This is just evil,” or simply, “Satanic.” And as one performer was raised on a barbed trapeze, suspended by meathooks through the flesh of his back, a man standing near me said, “This can’t be legal.” Folks walked away in droves from these horrific sights, wagging their heads in disgust.

Flash forward to the year 2016. Every waitress under thirty seems to have a mandatory tramp-stamp as well as a nose, lip, brow, or tongue ring. It isn’t unusual for her to sport full-sleeve tattoos on top of that. Baristas now typically look like they stepped right off that freak show stage back in 1990. On a recent layover in Long Beach, CA, I was served by two young ladies at a coffee bar; one had half her head shaved, the remaining hair dyed neon blue, and her ears full of so many piercings every turn of her head sounded like someone sifting pockets full of change; the other had a short boy’s haircut bleached platinum, and purple leopard print tattoos covering her neck, the hollow of her cheeks, and her forehead, as well as piercings in her nose and lip.

What two and a half decades ago struck middle-class Anglos as preternaturally evil is now normal amongst middle-class teachers, administrators, and police alike. Yes, even though police hiring practices in the past stipulated that their recruits bear no visible tattoos, that practice has obviously been retired, as I myself have come to meet police with tattoos on hands, necks, and faces. What disturbed the Orange County audience twenty-six years ago is become mainstream.

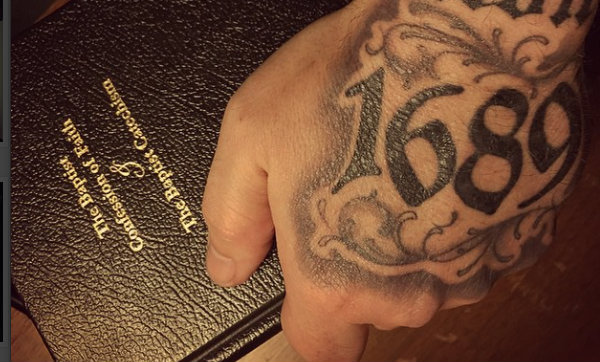

Worst of all, this Marilyn Mansonization of White America has permeated beyond the threshold of middle-class normalcy, even breaching now the inner ministerial corps of the churches. This phenomenon seems to have made landfall in the pastorate through two separate but mutually reinforcing channels – on one hand, the Charismatic prison and biker ministries such as Set Free with their emphasis on “recovery” paved the way for “leaders with a past,” and on the other hand, the advent of the novelty known as “youth ministry.” Inasmuch as the former was seen as a missions effort to the dregs, conservative Christians tended to say, “Well, I’m glad someone is reaching out to the criminals,” few entertaining the idea of promoting Hell’s Angels to leadership in middle-class suburban congregations.

But the latter (youth ministers) were accepted out of seminaries and Bible colleges with little ‘past’ of which to speak, just liberalized theology: here they came, gel-spiked hair, pierced ears, and tattoos of everything from crosses and burning hearts, to Greek and Hebrew script all over them. Even though the second group were not evangelizing habituated criminals, they too were endorsed in the assumption of an emphasis on missions work of a sort – covenant children. Despite their official positions on the status of covenant children, the concession made in most Reformed congregations in favor of youth ministry tacitly smuggled in a very Arminian doctrine of the child – that children are somehow apart from the Church and their parents and must be wooed, cajoled, and evangelized in much the same manner as if they were unbelievers. Albeit, this curious doctrinal digression is not entirely mysterious: because so many have so long kept their children in the deteriorating state school systems, those covenant children began appearing as if they were institutionalized hedonists just as all the criminals with whom Set Free and Chuck Colson’s Prison Fellowship dealt. If men with all the outward affectations of heathens could get at the hearts of rapists and murderers on death row, then young men with all the same outward heathen markings might also bridle the spirits of budding criminals within our church families. Unrepentant of this multi-generational madness of entrusting their children to the priests of Baal, the churches turned to priests of Jeroboam for remedy.

Now, less than thirty years since I saw crowds of middle-class White folks turn with disgust from those glorying in these pagan tropes, many men in otherwise conservative pulpits today have come to look just like members of that satanic freak show themselves. They are not, by and large, warding others way from such practices, making of themselves a cautionary tale, but rather, overtly encouraging the same. Even the new CEO of the purportedly theonomic American Vision, Joel McDurmon, typifies this new Christian* culture, mirroring what was identified as satanic rebellion against Christ up until two and a half decades ago.

Every single attempted justification of the practice on the part of these enlightened churchmen which I have read run exactly like all the pro-sodomite arguments people attempt to impose on the text – nothing but a protracted exercise in obfuscation and denial amounting only to the original rhetorical cavil, “Hath God truly said?” (Gen. 3:1).

Consider the history: the word tattoo is a Polynesian import to our language courtesy of the Cook expedition in Tahiti circa 1766-1779. Though our people in pre-Christian times had engaged in like practices, we had under God’s Law (Lev. 19:28) long regarded all such scarification as connotative of witchcraft and cursing like unto Cain’s mark; and on that basis, such practices had become virtually unknown amongst us until the era of exploration which brought us into the orbits of heathen races. The dividing line was stark. Tattoo-scarification in some form or other, was found ubiquitous amongst the pagan nations, but it was taboo among us; taboo itself, being another word appropriated from the same source and time (the root, ta, meaning ‘mark’), almost as if these rhyming Polynesian words were conceptual bookends perfectly suited to one another in the minds of the Christian sailors. For the tattoo was certainly, to us, taboo.

But it was Cook’s men who, falling to lust, took up with many native women during their extended furloughs. Those liaisons with strange flesh were synonymous with augmentations to their religion – sex is always tightly entwined with faith – which, in turn, resulted in consent to alien rites, including those cursed marks in the flesh which we know as tattoos.

In part, however, such markings would prove to have a practical inducement too, as those seamen who participated in such suddenly found in it the benefit of tailoring their own birthmarks, as it were, for purposes of identification in the case of death. This ensured that their contracts would not be voided by claims of desertion or AWOL. This meant that their families were more likely to receive payment on the sailor’s bond. Nonetheless, this practical usage was stumbled upon incidentally.

But the heathen connotation of tattoos was still taken entirely for granted a century later in Melville’s Moby Dick (1851), wherein we read of captain Ahab’s descent into madness leading to a renouncement of the Christian faith punctuated by a ceremonial session of tattooing by which Ahab says he has joined his “heathen brothers” – Polynesian, Amerind, and African harpooners. Which is to say that it was still, mid-nineteenth century, comprehended as sacrilege tantamount to selling one’s soul to the devil.

Because long before our exploratory and evangelical interactions with other races, and prior to the term tattoo, Kramer wrote in Malleus Maleficarum (The Witch Hammer, 1486) of “Devil’s Marks” taken in token of compacts with Satan. French Huguenot Lambert Daneau reiterated this in his treatise Dialogus de veneficiis (A Dialogue of Witches, 1564) describing the practices of ritual scarification typical of European witches (those persisting in pre-Christian paganism). Such markings were accepted as circumstantial evidence of witchcraft in the courts of Calvin’s Geneva, and more famously, in those of Puritan New England under Justice Sewall and the Reverends Mather.

Moreover, the association of tattoo-scarring with devilry had also been deeply impressed upon the Christian conscience through story, such as in the case of old Doctor Faustus (1604), who, having sold his soul to the demon Mephistopheles, was ‘marked’ with script which hinted at the curse of Cain – Homo, fuge!, “Flee, man!”

Due, then, to the implied atavistic malevolence in those lingering strains of heathendom, it came as little surprise in the early twentieth century when the practice began to spread from the docks and wharf towns to the criminal class at large.

In 1913, Dr. Charles Goring (father of the distinguished actor Marius Goring), a prison doctor, published a vast compendium of statistical information about criminals called The English Convict, in which he wrote: “It was originally asserted by Lombroso [the famous Italian doctor, anthropologist and criminologist], and the statement has been confirmed by observers, that the criminal displays an inordinate tendency to tattoo his body — the tendency being regarded as an atavistic revival of the love of ornate display which characterises the savage.”1

This correspondence would be reified in the mingling of vagabond criminals and occultists in the phenomenon of the Circus Sideshow. Those with tattoos and other marks of self-mutilation there became a penchant spectacle of the Freak Show. Which is where it had more or less remained up to the time of my childhood as was evident from the crowd’s reaction to the Jim Rose Circus all those years ago.

But today all these atavistic, occultic, and heathen expressions have become mainstream in pew and pulpit. Rather than baptizing saints, we have baptized sin; and presently, we are midway to turning sacrilege into sacrament.

Underscoring its permanence, and in thorough keeping with the confession, Rushdoony explains the case law against scarification in Leviticus 19:28 to be derivative of the 6th Commandment:

Adam Clarke, a couple of centuries ago, in line with the practice of the church from the beginning, listed as violations of the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” all ascetic practices that did harm to the body. Suicide, drunkenness, gluttony, a general intemperance of character. Also among the personal violations of this commandment are any actions which deface or harm the body.

Among those specifically listed in the Scripture are the tattoos. The body must be used under God and kept for his purposes and is not to be defaced. It is significant that the tattoo mark has an origin in religion, in paganism. It indicated two things in pagan societies: one, that the person was a slave of a particular God. Second, that he was the slave of a particular person. A tattoo is a mark of slavery, and it is ironic that it should become so popular for it has always, until fairly recent times, retained that meaning. And slaves were tattooed. This was until fairly recent times, the means of identification, and still is in some parts of the world. But in Bible times not even a slave could be tattooed, he was still God’s before he was man’s.2

In any case, a covenant involved the whole of man; it was a “body and soul” commitment, and body markings which manifested a man’s covenant with his god were commonplace in the Near East. Because God as covenant Lord is the owner of all things, including our bodies, His covenant law forbids any and all mutilations of the body, whether for mourning, or as a covenant mark with men or gods. Only His covenant mark, circumcision for men, is lawful (Lev. 19:28).3

The nature of said laws forms a hedge of protection for the telos of Man as the imago Dei. As Francis Schaeffer argued, Man has an image mandate delegated to him from God – to be Man, and the Executor of God’s estate on earth. As image-bearers, men are not at liberty to make of themselves billboards for anything else – not even, as in the cases of Christian* tattoos, pretensions of improving upon God’s design.

To presume some right to overrule God’s express design through Body Modification may more poignantly be called “Transhumanism,” for men’s self-recreation with its attendant sanctifications (or markings) of the body, flies in the face of Christ’s recreation and sanctification of Man. And in some essential regard, by the transcendence of their ascribed nature and design, men become something slightly other than what they were designed to be, which is to say, inhuman in some way, their outward disfigurements expressing the inward distortions of being.

Albeit, none of this is to say that those who may have scarred themselves in such ways are irredeemable. Far from it. But if they in the Church bearing such marks do not make clear their repentance of those things and dissuade others from the same, preferring instead to justify their violations of the perspicuous intents of the law and creation on the heretical grounds that “it isn’t about the skin, but the heart” – a Gnostic denial that Christ deals with the whole man, body and soul – such as is the norm presently, they have resolved themselves to impenitent Gnosticism, in which case there is more than ample reason to doubt their redemption.

Footnotes

- Theodore Dalrymple, “A Few Arguments Against Tattoos” ↩

- R.J. Rushdoony, Pocket College transcription of “Sixth Commandment” ↩

- R.J. Rushdoony, Systematic Theology, p. 427 ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|