Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: McDurmon’s Rejection of Christendom and Embrace of Egalitarianism

Part 3: McDurmon’s Use of Sources

Part 4: The Slave Trade and Slave Breeding

Part 5: Rape

Part 6: Separation of Families and Systematic Injustice

Part 7: Cruel Punishment and Corporal Mutilation

In this concluding edition of our review of McDurmon’s new book on slavery, I consider crucial oversights of relevant material from McDurmon’s portrayal of American history regarding race relations between whites and blacks.

In addition to the many problems with McDurmon’s presentation of the history of American slavery, there is also a substantial issue with omissions. To start, McDurmon omits any reference to black slaveowners. Black slaveowners persisted throughout the antebellum period and were by no means an anomaly. In fact the transition from indentured servitude to permanent enslavement was facilitated by a free black named Anthony Johnson of Maryland, who filed a suit in court to have his indentured servant John Casor declared his servant for life.

McDurmon’s presentation follows the mainstream narrative that only blacks have been slaves. Entirely omitted from McDurmon’s discussion is any discussion of white slaves. The enslavement of whites was not confined to Muslim Barbary pirates, but was practiced by whites towards other whites in Britain and America. The reality of slavery is that harsh conditions were endured by many people in even the recent past, and this was by no means confined to blacks. Michael Hoffmann details the history of white slavery in his excellent book, They Were White and They Were Slaves, and it is noteworthy that many considered the conditions of black Southern slaves to be superior to white slaves during the same time period.

As much as these facts would have helped to balance McDurmon’s narrative, perhaps the most serious issue in McDurmon’s book is how he deals with the Nat Turner uprising. What is particularly troublesome is what McDurmon does not say. McDurmon briefly mentions the Nat Turner uprising as a pretext used by Southern whites to strip blacks of their already meager rights:

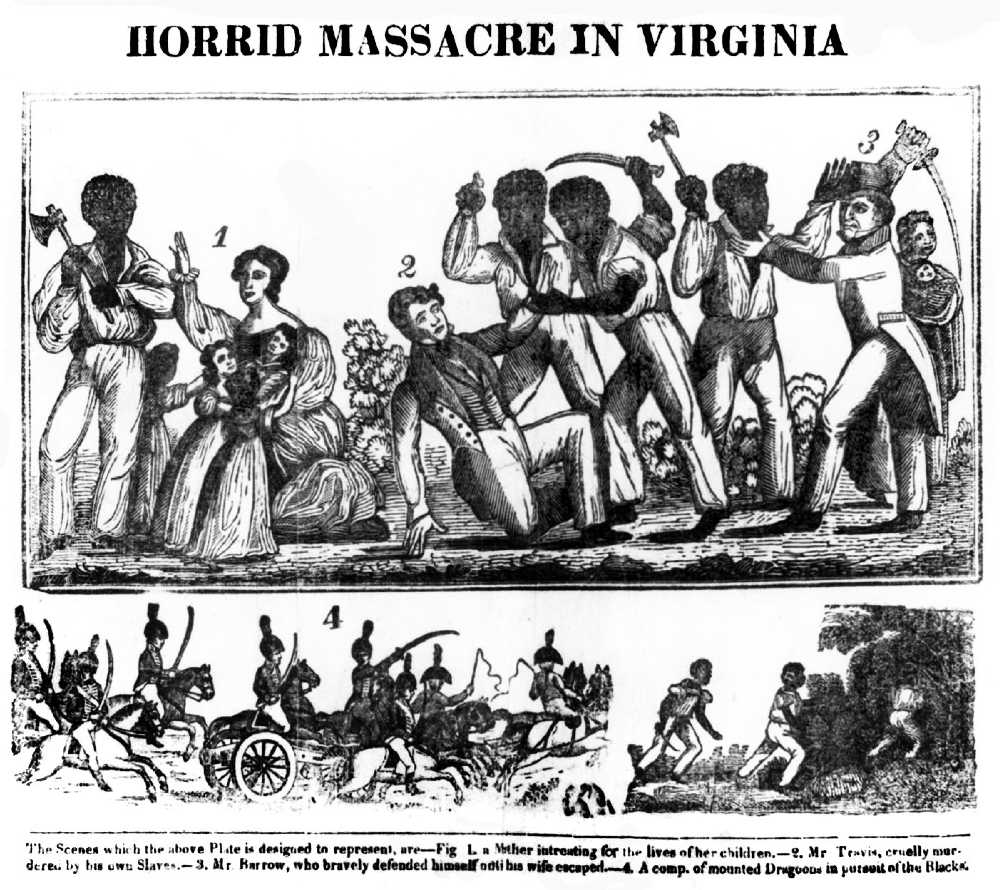

[O]ne of the most notable slave revolts broke out in southeastern Virginia in the fall of the same year [August 1831]. No sooner had southerners feared that the spread of radical Garrisonian abolition would stoke slave unrest, than did the charismatic slave preacher Nat Turner lead one of the largest, if not the largest, slave rebellions in American history, killing about 60 whites in the space of two days. Militias organized and put down the rebellion, but overzealous manhunts continued for several days. Even after they had captured all the conspirators, white vigilantes rounded up countless alleged rebels, and in apparent racial revenge decapitated them and placed their heads on poles.

‘In all directions whites took Negroes from their shacks and tortured, shot, and burned them to death and then mutilated their corpses in ways that witnesses refused to describe.’ In all, about 120 blacks suffered this torture and execution, on top of over 50 formally executed by the state. When Turner himself was finally caught, he suffered the same fate.1

McDurmon’s account of Nat Turner’s massacre betrays what can only reasonably be described as anti-white hatred. McDurmon casually describes Turner as a “charismatic slave preacher.” McDurmon’s account would have his readers believe that Nat Turner led an uprising that simply killed “about 60 whites in the space of two days.” Completely missing from this account is the fact that among these “60 whites” were numerous women and children. Many might surmise that Turner was motivated to this indiscriminate slaughter based upon personal experiences of harsh treatment, but this was not the case.

Turner’s confession that he made to Thomas R. Gray is as enlightening as it is disturbing. Turner described his master, Mr. Joseph Travis, as “a kind master” who “placed the greatest confidence in me; in fact, I had no cause to complain of his treatment to me.”2 Gray lists the victims of Turner’s murderous rampage, “Joseph Travers [Travis] and wife and three children, Mrs. Elizabeth Turner, Hartwell Prebles, Sarah Newsome, Mrs. P. Reese and son William, Trajan Doyle, Henry Bryant and wife and child, and wife’s mother, Mrs. Catharine Whitehead, son Richard and four daughters and grand-child, Salathiel Francis, Nathaniel Francis’ overseer and two children, John T. Barrow, George Vaughan, Mrs. Levi Waller and ten children, William Williams, wife and two boys, Mrs. Caswell Worrell and child, Mrs. Rebecca Vaughan, Ann Eliza Vaughan, and son Arthur, Mrs. John K. Williams and child, Mrs. Jacob Williams and three children, and Edwin Drury–amounting to fifty-five.”3

The horrors of the Turner insurrection demonstrate that these were the actions not of the righteously indignant, but of bloodthirsty murderers. Turner describes ambushing his master’s family in the middle of the night while they slept. Travis and his wife and children were hacked to pieces by hatchets and axes. The goons left the house, but returned when they remembered that they had forgotten to kill Travis’s baby! Turner stated, “The murder of this family, five in number, was the work of a moment, not one of them awoke; there was a little infant sleeping in a cradle, that was forgotten, until we had left the house and gone some distance, when Henry and Will returned and killed it.”4

Turner’s rampage continued. After being chased down and cornered in a cotton field, the Rev. Richard Whitehead, who had once allowed Turner to preach in his churchyard, pleaded for answers, only to hear in response, “Kill him! Kill him! Kill him!” Turner’s men annihilated a schoolhouse full of children. Rebecca Vaughan was praying as she was murdered. Captain John Barrow, a veteran of the War of 1812, fought his assailants to the bitter end, and he killed several attackers with his musket, pistol, and sword before being overwhelmed by sheer numbers. Turner and his insurrectionists are reputed to have drunk Barrow’s blood because of his bravery.5 Thomas Gray concluded, “No cry for mercy penetrated their flinty bosoms. No acts of remembered kindness made the least impression upon these remorseless murderers. Men, women and children, from hoary age to helpless infancy were involved in the same cruel fate. Never did a band of savages do their work of death more unsparingly.”6

McDurmon’s omission of these essential details decontextualizes the white response throughout the South. McDurmon misleads his readers into believing that the white reaction was hysterical and paranoid, when the reality is that this was largely a reasonable response to a terrible atrocity. What of the unbridled violence that McDurmon reports? McDurmon alleges that “about 120 blacks suffered this torture and execution, on top of over 50 formally executed by the state.” McDurmon’s main sources for this claim are “Children of Darkness” by Stephen Oates and “The Aftermath of Nat Turner’s Insurrection” by John W. Cromwell.7 Oates’s article was published relatively recently (1973) and is lacking in citations of source material. Cromwell’s article is older (1920), but the source (which McDurmon omits) for torture and rampant violence is only said to be “[b]ased on statements made to the author by contemporaries of Nat Turner.” Needless to say, this is pretty weak.

Contemporary historian Patrick Breen has thoroughly studied the Turner insurrection. Breen argues that the state of Virginia and local militias were motivated by a desire to convince white Virginians that slavery was still safe to practice, and to prevent further slave uprisings and additional abolitionist activism. Breen also argues that efforts made by the state to contain violence were largely successful. Breen concluded based upon virtually all the relevant records of the time period that blacks killed by whites without a trial in the aftermath of Turner’s insurrection number in the thirties – nowhere near the estimation that McDurmon cites as evidence of widespread white violence against blacks. Those blacks killed were adult men suspected of having participated in Turner’s rampage.8

Furthermore, McDurmon inaccurately states that “over 50” blacks were “formally executed by the state” for their participation in Turner’s rebellion. The truth is that 53 black men were arrested, but of those arrested 20 were convicted and executed, 12 were removed from the state, and 21 were acquitted.9 This hardly suggests the unmitigated bloodlust that McDurmon imagines. These oversights on McDurmon’s part entirely misrepresent the response of Southern states. The efforts taken by the Southern states, such as forbidding the teaching of reading and writing to slaves, may seem overly severe or harsh by modern standards, but these were passed in order to prevent horrors like the Nat Turner insurrection or the massacre of whites in Haiti from happening again. McDurmon’s silence regarding these crucial facts is dishonest and inexcusable.

Conclusion

The topic of slavery is not merely a historical question, but has great relevance for us today. Our perceptions of present realities are influenced and ultimately determined by our perception of the past. McDurmon’s work is essentially a rehash of contemporary Marxist scholarship. The only thing that makes McDurmon’s account unique is that unlike the Marxist historians and academics he repeatedly cites, McDurmon claims to be defending traditional Christian ethics as taught by God’s Law. None of these same academics would take such a claim seriously because it is absurd. The Bible allows for and regulates the institution of slavery. That much is clear, and McDurmon’s silence on virtually all of the relevant Bible verses speaks volumes.

Those who promote a false narrative about the harshness of American slavery are all too eager to blame the Christian faith. McDurmon has repeatedly promoted this book by arguing that it is needed now more than ever. The truth is that the perspective that runs throughout the entire book is in lockstep with the sociology departments of every college and university, as well as the entertainment industry. This book is simply one more voice in our modern anti-white and anti-Christian echo chamber.

James Henley Thornwell, one of McDurmon’s chief villains, warned a century and a half ago about the true nature of the dispute:

The parties in this conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders—they are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, jacobins on the one side, and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battleground—Christianity and atheism the combatants, and the progress of humanity at stake.”10

The Jacobins won the war and the religion of equality has carried the day well into the twenty-first century. Today we are reaping the bitter fruits of this anti-Christian ideology. McDurmon’s book can serve only to further the narrative that Christendom and white Christians have always been cruel and oppressive. It will empower secularists who wish to deride Christian ethics and continue to stoke the flames of black resentment against whites. I only wish Joel could see just how much harm his book has the potential to do. Our only hope is that white Christians will one day, by the grace of God, be awoken from our long stupor so that our children and grandchildren may be delivered from the disaster that these leftist lies have created. Fortunately, truth will ultimately triumph over falsehood, and McDurmon and his Jacobin disciples will discover that they have been on the wrong side of history all along.

Footnotes

- McDurmon, Joel. The Problem of Slavery in Christian America (Kindle Locations 2904-2914). American Vision Press. Kindle Edition. ↩

- Gray, Thomas R. The Confessions of Nat Turner: The Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, VA. Electronic Edition, p. 11. ↩

- Ibid. p. 22. ↩

- Ibid. p. 12. Emphasis mine. ↩

- I initially read this account on The Right Stuff in Silas Reynolds’s article the recent Hollywood glorification of Nat Turner called, The Birth of a Nation. The article is now behind the TRS paywall. ↩

- Gray, Thomas R. The Confessions of Nat Turner, p. 4. ↩

- Stephen B. Oates, “Children of Darkness,” American Heritage: The Magazine of History 24, no. 6 (October 1973): 89. John W. Cromwell, “The Aftermath of Nat Turner’s Insurrection,” The Journal of Negro History 5, no. 2 (April 1920): 213. ↩

- See Patrick Breen’s presentation in Richmond, Virginia before the Virginia Historical Society given on November 11, 2016. Breen’s relevant comments begin around the 23:00 mark. ↩

- See also Gray, Thomas R. The Confessions of Nat Turner, pp. 22-23. ↩

- McDurmon repeatedly and inexplicably refers to Thornwell as John in his book. At one point he chides Thornwell for refusing to discuss the matter of slavery with Scottish or Irish Covenanters who continued to slander the South for slavery. McDurmon calls Thornwell’s threat to break off communication “Threatening a nineteenth-century equivalent of ghosting or blocking someone on social media, he said correspondence with the churches of Ireland and Scotland would ‘cease’ unless they ‘drop the subject of Slavery.’” (Kindle Locations 6583-6584) It makes perfect sense that Thornwell would consider repeated false accusations from Covenanters beneath the dignity of a response, but this is hilarious coming from McDurmon, who blocks everyone who has the temerity to disagree with him and summarily deletes dissenting comments on American Vision. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|