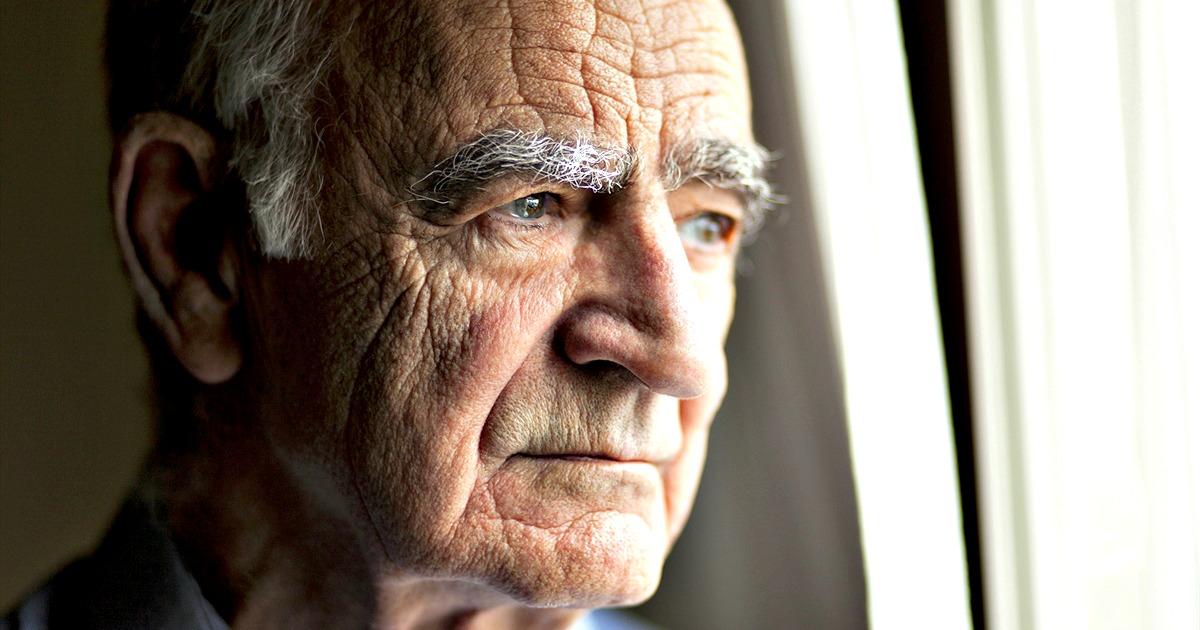

It’s 2037, and all the kids have grown up and moved away. As much as they could, at least. Jobs are hard to find for white men and safe neighborhoods are difficult to find for white families. You’ve kept your nose to the grindstone for decades now in order to bring in as much income as possible without betraying your core values, and to give your wife and children as normal a life as could be had in early 21st-century America.

You homeschooled them to keep them from pedophiles, homosexuals, and anti-white beatings. You homechurched them to keep them from the heresies of white guilt and feminism that took over the conservative churches in the 2010s. You moved from job to job in a vain quest to piece together the life that your parents and grandparents led, when jobs could be profitable and carried good health care and retirement benefits. You never enjoyed that. You are the working poor, always putting in more than 40 hours a week but rarely making enough to put you over the poverty level. The fact that you had a big family didn’t make that easier, but you obeyed God, kept your wife at home, and treated babies as a gift and not a burden. Little by little, you scraped together enough savings to buy a small home. It’s never been easy to make payments, keep up with maintenance, or pay the rising property taxes in your once-decent, now deteriorating school district. Crime is now a problem. You feel like there’s nothing you can do to maintain your property’s value. You feel helpless to ensure that your wife will have a safe, happy home in her old age.

It didn’t used to be this way. When you moved to your neck of the woods in the 2010s, there were still vast stretches of the United States that remained safe and homogeneous. That changed thanks to the active breakup of such white enclaves by federal and nonprofit agencies beginning in the 2000s. Refugees and minorities became the demographic majority after the failure of the Trump Administration to do anything serious about white genocide. Still, you and your wife have managed to keep things semi-normal for yourselves and the kids, despite the loss of any implicitly white spaces in your society. Your churches, schools, grocery stores, sports teams, media, businesses, parks, and neighborhoods have all been infiltrated and occupied by strangers. Your children and future grandchildren are strangers in their own country. You feel genuine fear at what your yet-unborn grandchildren will have to endure.

When you were still a young man in the 1990s and 2000s, you believed it when your pastors and Republican politicians told you that the increasing racial diversity in America would be a blessing, and a divine plan to atone for the alleged sins of white racism. You felt a little more comfortable hearing that there was only one race, the human race, and that skin color was an irrational basis by which to categorize people. Why should you care what people look like since we’re all the children of God?

In 2037, however, you’re a different man. Through personal experience, you have learned that those pastors and politicians were making false promises. Life has not gotten better for you with diversity. It has gotten worse. You haven’t reached the level of suffering that your brother has, though. Years ago you moved across the state for a new job, but your brother stayed behind. He comes over annually for Thanksgiving, and he has plumbed the depths of the lies those pastors told you years ago.

He was there in the emergency room after two black men sexually assaulted your niece in broad daylight in your hometown. Your brother’s church (the one you grew up in) was recently vandalized by non-whites on account of its supposed white supremacism. Didn’t they know that your old pastor had preached to the congregation for thirty years about why they should adopt non-white orphans, and that half of the church had interracial marriages? Now that the new pastor is brown and all but one of the elders are non-white as well, your brother finds it curious that even when they’ve got all the power, they keep harping on the white members of the flock to not file their reparations payments late. That would be sinful, they say annually as white citizens prepare to file their taxes and contribute a mandatory extra 10 percent income tax to the federal “social justice fund”. He sadly nods when you tell him how it’s funny the non-white elders didn’t complain about the godlessness of the 2010s Black Lives Matter movement, and hold up the communist-organized 1960s civil rights movement as a quintessentially Gospel-centered moment in history.

You’ve long since grown tired of all this, but he is still on the fence. He considered no longer going to church two years ago when the non-white pastor and elders endorsed a pro-abortion, pro-Islamic presidential candidate on account of his commitment to “racial reconciliation.” Unfortunately, since his kids grew up in the youth group and were conditioned to equate their faith and patriotism with multiculturalism and miscegenation, your sister-in-law and nieces and nephews wouldn’t go along with your brother’s idea. He and his wife and kids don’t talk much about important things anymore, since all they do is fight when such topics come up. Your sister-in-law has taken him to the elders for resisting her half-cocked ideas about how the household should operate, and for not sufficiently treating her like a queen. He considers it a relief to be able to unburden himself to you in person. Phone and online chats are routinely monitored by the government now, and he doesn’t know any other white men who admit to being fed up, so he rarely feels at ease to speak his mind.

You’re glad that you’re not in his shoes. Still, in your late 50s, you wonder how you’re better off. You don’t have the family strife he does, since your wife and kids avoided the spiritual poison pastors began feeding their flocks decades ago. However, your kids and grandkids will have a hard time finding like-minded people to marry, to befriend, or with whom to worship or go into business. You’ve succeeded in holding off the worst effects of degeneracy for your kids’ childhoods. But it seems like all you’ve done is carry out a delaying action. What comes next is virtually unstoppable. There are no pro-white church denominations. There are no pro-white politicians or major political organizations. The anti-white government has clamped down on everything over the years to the point that samizdat is about all that remains of a resistance movement (and that is limited to a few hardy, tech-savvy individuals). The United States is beginning to resemble South Africa in the 2010s, when white farmers would be routinely raped, tortured, and murdered in their own homes by marauding blacks…and no one cared.

As a young man, you learned that one of the most important ways you could make decisions was to answer the question, “On my deathbed, what will I wish I could have had more of?” You knew that you wouldn’t pine for wealth on your deathbed, so you put aside materialism and the desire for fame in order to give your life to Christ and live with an eternal perspective. You knew that on your deathbed you wouldn’t linger over the memories of illicit pleasures, so you turned away from sexual temptations in order to honor God in your body and in your marriage. You knew that other accomplishments in this life would pale in comparison to the legacy you left in the persons of your children, so you prioritized building up your children and are grateful to have a realistic hope of seeing them carry on your faith and values in their and successive generations.

But now you realize that there was another question you should have asked yourself all those years ago. You had so much right, and yet as you approach your senior years you feel dread. While you prioritized the most important things in life for the sake of God and family, you neglected to prioritize what kind of world your kids would have to live in once you passed away.

Now you ask yourself, “If I had done something differently years ago, would my children’s prospects today have been better or worse?”

As you consider all the ways in which you could have done something differently and determine whether things would have worked out better or worse, you are glad you didn’t do the things that would have made their childhoods and adulthoods worse. You did the right thing in these cases.

But sometimes you find yourself thinking that things would have been better. In those cases you ask yourself, “Why didn’t I do it?”

And then you feel confusion. Regret. Anger. And shame.

| Tweet |

|

|

|