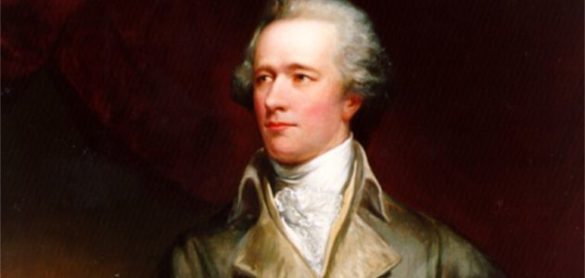

The reputation of Alexander Hamilton is not typically held in high regard by very many Southern paleo-conservatives or nationalists. Many Southerners view Hamilton as the foil to the virtuous Southerner Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton and Jefferson certainly were political rivals, so perhaps it is natural that many Southerners view Hamilton as the Yankee antithesis to Jefferson’s Southern agrarianism. This contrast is not without merit, but this approach is also oversimplified and anachronistic, reading the sectional conflicts of the North and South of the mid-nineteenth century into the time of Hamilton and Jefferson. The early post-Revolution years in America were less defined by the regional polarization that would lead to the Civil War several decades later.

That’s not to say that national politics did not have the general contours of the sectional conflicts that were to emerge, only that they were not quite so polarized as they would later become. Hamilton is criticized by many traditional conservatives, in particular those from a Southern background, for several of his political causes. He can certainly be blamed by fair-minded thinkers on the Right for the errors in his thinking. My aim is not to provide a comprehensive defense of Alexander Hamilton or the obvious problems in his thinking on certain political and economic issues, but rather to offer some considerations as to why I believe that Alexander Hamilton is not the historical boogeyman that some make him out to be. Consider the following:

Jefferson’s Thinking Was at Least as Flawed as Hamilton’s

In our contemporary circumstances we tend to think of politics as a civilizational conflict between good and evil in which foundational principles like marriage and abortion rights are debated in national elections. This was not the case in America during the late eighteenth century. There was a broad consensus among Americans on matters of importance, and this consensus was informed both by conservative Protestantism and Enlightenment rationalism. I am of the opinion that Hamilton and Jefferson both have admirable qualities as well as blind spots and flaws in their thinking. Both men made admirable contributions to the American political tradition, and their disputes were over topics in which good men of that time often disagreed. While both Hamilton and Jefferson had many admirable qualities, both men made misjudgments that must be discerned as well.

Southern nationalists and traditionalists are well aware of Hamilton’s shortcomings. Hamilton was an advocate of a strong federal government, centralized banking, a standing army, and the creation of the national debt that has been the bane of the American people for centuries. The nostalgia for Jeffersonian ideas has become particularly acute given our current political circumstances. We live under an oppressive, centralized Leviathan government that has entirely subsumed the states as mere jurisdictional subunits of itself. The judicial branch, which Hamilton favored, has become a dictatorial juggernaut that enforces leftist ideas and voids conservative victories in the legislative and executive branches. We are constantly embroiled in perpetual war, ostensibly for the purpose of establishing perpetual peace. Our national debt, once championed by Hamilton as a unifying force, has grown at such an alarming pace that it is mind-boggling to consider the extent of how much the federal government owes.

Jefferson’s Southern agrarian ethos is a good corrective for many of Hamilton’s errors, but Jefferson was also wrong on many topics as well. Jefferson was enamored of the French Revolution and even initially resisted denouncing the senseless violence that has become known as the Reign of Terror. Jefferson was firmly entrenched in the prevailing Enlightenment optimism in man’s inherent goodness and perfectibility. To Jefferson, the French Revolution swept away centuries of meaningless and oppressive superstitions that would give way to a new era of freedom and Franco-American friendship. Needless to say, Jefferson’s confidence was misplaced, and Hamilton’s skepticism of human nature grounded in traditional Christian anthropology has been thoroughly vindicated.

Hamilton’s Errors Were Not Unique or Original to Him

The errors in Hamilton’s thinking were not original to him. Centralized banking had emerged in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, and came over to England with the Glorious Revolution and the ascendancy of William of Orange as King William III. Hamilton grew up in the Dutch West Indies and admired the close relationship between the Netherlands and Great Britain. The historian Michael Hoffman details in his book, Usury in Christendom: The Mortal Sin that Was and Now Is Not, how interest (usury) gained gradual traction among Christian thinkers after initially being rejected as inherently sinful. Whatever the flaws in Hamilton’s thinking, they were already entrenched in the economies of Western Europe, and it is unlikely that modern banking practices would have been kept out of American politics even without Hamilton’s influence. Hamilton’s concern for order, rank, and traditional values place him firmly within the Tory camp. I am sympathetic to Tory ideas, but I also understand the flaws that have emerged from this tradition as well. Hamilton was not the first or the last example of the misjudgments about society that he made.

Hamilton Was a Genuine Christian in an Age of Skepticism and Deism

As I previously mentioned, many of America’s Founding Fathers were raised within an Anglo-Protestant milieu. Most of them were brought up in the Anglican or Congregationalist churches, with a handful of Dutch Reformed, Presbyterians, Methodists, and a few Papists sprinkled in the mix. The early American republic was thoroughly saturated in Protestant culture, but by the mid- to late eighteenth century, deism had become a popular trend. Deists believe in a single creator God but reject supernatural revelation and miracles. Many Christians in America and Europe adopted a deistic worldview, even though they remained culturally Christian and continued to attend church and observe religious holidays. Alexander Hamilton was not dissimilar from many of his contemporaries. He was raised in the Dutch Reformed Church and married Elizabeth Schuyler of a prominent New York Dutch Reformed family. Hamilton read the daily offices from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer every day.

After his fatal duel with Aaron Burr that would take his life in 1804, Hamilton spoke with his friend Rev. John Mason, a prominent Presbyterian minister. Rev. Mason denied Hamilton’s request to receive communion before he died because it was not the practice of the Presbyterian Church to administer communion privately. Hamilton called upon the Episcopal Bishop of New York and Rector of Columbia University (formerly King’s College), Benjamin Moore, to administer last rites and communion.1 Moore agreed only when Hamilton agreed to renounce dueling and dispensed communion upon receiving Hamilton’s confession of faith. Hamilton spent his final hours singing hymns surrounded by his wife and children.

Hamilton also lived out Christian virtues throughout his life, and demonstrated tremendous fortitude during his formative years on the islands of Nevis and St. Croix in the West Indies. Hamilton’s parents, James Hamilton and Rachel Faucette, were not properly married, and his father abandoned the family when he was young. Hamilton did not bear ill will against his father, and even sent him money to care for him in his old age. Hamilton also took pride in his ancestry, naming his family estate The Grange after his family’s ancestral seat in Scotland.

Alexander Hamilton Generally Supported The South

Alexander Hamilton has come to be known by some as a Yankee who was diametrically opposed to the ways of the South, but this is an unfair and inaccurate characterization. Hamilton’s opposition to slavery was very distinct from the radical abolitionism that would spread throughout the North in the decades following Hamilton’s death. Hamilton championed the gradual manumission of slaves as a member of the New York Manumission Society. Like the later philanthropic organization, The American Colonization Society, the NYMS was a moderate institution that advocated gradual manumission of slaves as opposed to outright abolition. Hamilton remained a cautious opponent of slavery because of his friendship with slave-owners and Hamilton’s desire for a federal union. There is no basis for the idea that later abolitionists, who were willing to burn the Constitution in order to abolish slavery, had anything in common with Hamilton.

Hamilton was a lifelong friend of George Washington, and served as his second-in-command or aide-de-camp during the Revolution. Hamilton’s closest friendship was with John Laurens of South Carolina, the son of the President of the Continental Congress Henry Laurens. Hamilton was crushed when he received the news of John Laurens’s death in the final days of the Revolution. Hamilton lobbied Patrick Henry of Virginia to stand for election as president in 1796 to succeed George Washington. Hamilton also favored Southern Federalists Thomas Pinckney and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney in the presidential elections of 1796 and 1800, respectively. In contrast Hamilton feuded, at times irrationally, with Massachusetts Federalist John Adams. Whatever his flaws, Hamilton was no enemy of the South.

Hamilton Was Concerned About Immigration and Foreign Influence

Alexander Hamilton was a skeptic of immigration and understood just as well as his fellow New York Federalist John Jay that America has always been a nation “descended from the same ancestors.” Hamilton was a strong supporter of the Naturalization Act of 1790 that limited citizenship in the United States to “free white persons of good character.” Hamilton had come to America during his young adulthood, but he still understood the necessity of America’s homogeneity as an ethnically European nation. Hamilton wrote, “The safety of a republic depends essentially on the energy of a common National sentiment; on a uniformity of principles and habits; on the exemption of the citizens from foreign bias, and prejudice; and on that love of country which will almost invariably be found to be closely connected with birth, education and family.”

Hamilton Was Rightly Skeptical of the French Revolution

Hamilton’s opposition to the French Revolution distinguishes him from many of his contemporaries, who were enthusiastic supporters of Revolutionary France. Hamilton wrote, “The politician who loves liberty, sees them with regret as a gulf that may swallow up the liberty to which he is devoted. He knows that morality overthrown (and morality must fall with religion), the terrors of despotism can alone curb the impetuous passions of man, and confine him within the bounds of social duty.”2

Hamilton believed that Americans should not support the overthrow of the French king and aristocrats who had supported the American cause for independence. Hamilton has proved prophetic in his denunciation of the ideology of the French Revolution, which has proved to be the downfall of the West. Hamilton was much more faithful to the traditional Christian understanding of man’s fallen nature, rejecting an unbridled optimism in the good judgment of the “common man” as the measure of all things. Hamilton also understood that morality is inseparable from religious beliefs. The abandonment of Christianity throughout the Europe and North America has absolutely ruined the moral conscience of the West.

My argument is not that Hamilton was a man without flaws in both his personal life and his political beliefs, only that he is not the villain some think him to be. Hamilton was a man of strong character, keen intellect, and a firm attachment to the welfare of his country. We can learn from his successes and failures, and count him as a worthy member of America’s Founding Fathers.

Footnotes

- As an interesting aside, Rev. Moore’s wife Charity Clarke was a cousin to Aaron Burr’s wife, Theodosia Bartow Prevost. Rev. Moore’s only child was a son, Clement Clarke Moore, a seminary professor and author of the famous poem, ‘Twas The Night Before Christmas. ↩

- “The Stand,” Works of Hamilton, V, p. 410. Quoted in The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot by Russell Kirk, Seventh Revised Edition, pg. 80. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|