Like many readers of Faith and Heritage I have an interest in European folklore and tradition. Ever since I was a child I have enjoyed reading stories of the exploits of courageous knights faithful in their service to God and their king. The romantic idea of knights in shining armor slaying dragons, fighting off invading heathens, and rescuing damsels in distress has always appealed to me, and it does so even more today because these ideas are so countercultural. As I’ve studied different folklore traditions, the legend of King Arthur especially stands out. Arthurian lore stands proud in the European canon of folk heroes. Particularly fascinating is that many European folk legends have a basis in reality. Recently I finished reading two books by Scottish author Adam Ardrey on the subject of King Arthur: Finding Merlin: The Truth Behind the Legend of the Great Arthurian Mage, and Finding Arthur: The True Origins of the Once and Future King. In these two books Ardrey seeks to establish the historical basis for the characters of Merlin in Arthur, but what makes his perspective unique is that he places these two figures not in England or Wales, but in Scotland!

Ardrey’s work is certainly tainted by an easily discernible anti-Christian bias. Ardrey sympathizes with the pagan Druids and is hostile to Christians and Christianity, even comparing the Christians of sixth-century Britain to the Third Reich. This anti-Christian perspective definitely taints Ardrey’s otherwise sound scholarship. Christians such as Mungo Kentigern are portrayed as unflinchingly cruel and evil. Furthermore, Ardrey’s anti-Christianity is of the egalitarian and liberal variety. One of his most ridiculous assertions is his account where King Rhydderch of Strathclyde forgives his wife’s adultery. Ardrey insists that this happened because…Rhydderch was a homosexual! No other evidence is presented. The mere act of forgiveness is all that Ardrey needs to make this vast leap. These arguments definitely taint Ardrey’s objective analysis of the facts of history in the eyes of any reasonable reader.

Nevertheless Ardrey provides interesting original scholarship on the question of a historical Arthur. Many modern scholars have dismissed Arthur as an almost entirely fanciful medieval myth. It is easy to understand why many scholars are skeptical given the sparse nature of sources attesting to the existence of men like Arthur, Merlin, and Lancelot. That being said, Ardrey produces compelling evidence to suggest that Arthur and Merlin were historical figures dating to late-sixth-century Scotland. The legendary Arthur and Merlin are well known, and their exploits are founded upon the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Brittaniae (History of the Kings of Britain, c. 1136) and Vita Merlini (Life of Merlin, c. 1150), as well as Sir Thomas Malory in his Le Morte d’Arthur (The Death of Arthur, c. 1485).

King Arthur is said to have been born at Tintagel Castle to Igraine, Duchess of Cornwall, after Merlin the magician casts a spell to make the lovesick Uther Pendragon appear to her as her husband Duke Gorlois, who conveniently dies in battle. Uther and Igraine marry, and Arthur is born only to be fostered to Merlin as a reward for his services. Merlin then sends the boy Arthur to be raised by the Knight Sir Ector alongside his own son, Sir Kay. After the death of Uther, who is said to be king of all England, a new king must be selected by a tournament to be held in London. A miracle occurs in which a stone with a sword stuck in it appears in a churchyard with a message that whoever could pull the sword from the stone was “rightwise king born of all England.” Arthur is present at this tournament merely as a squire to his foster brother Sir Kay. When Kay sends Arthur to fetch his sword, Arthur unwittingly retrieves the sword from the stone, and is acclaimed king after Merlin confirms his parentage. After the sword drawn from the stone breaks, Merlin provides Arthur with his legendary replacement, Excalibur.

Merlin assists Arthur in establishing the Knights of the Round Table at his court in Camelot after his marriage to Guinevere, while warning Arthur that Guinevere will someday prove unfaithful. Merlin’s prophecy comes to pass when Guinevere engages in an adulterous tryst with Sir Lancelot, the most skilled and valiant of Arthur’s knights. The treacherous Sir Mordred, Arthur’s wayward nephew, uses this affair to create discord among the knights, and ultimately Arthur and Mordred end up mortally wounding each other at the Battle of Camlann. The dying Arthur is taken to a magical island called Avalon in which he is laid to rest. Arthur is the epitome of the sleeping hero, a king who is said to be waiting for the hour of greatest peril for his people in order to return and rescue them from destruction, hence lauded as the Once and Future King.

Merlin

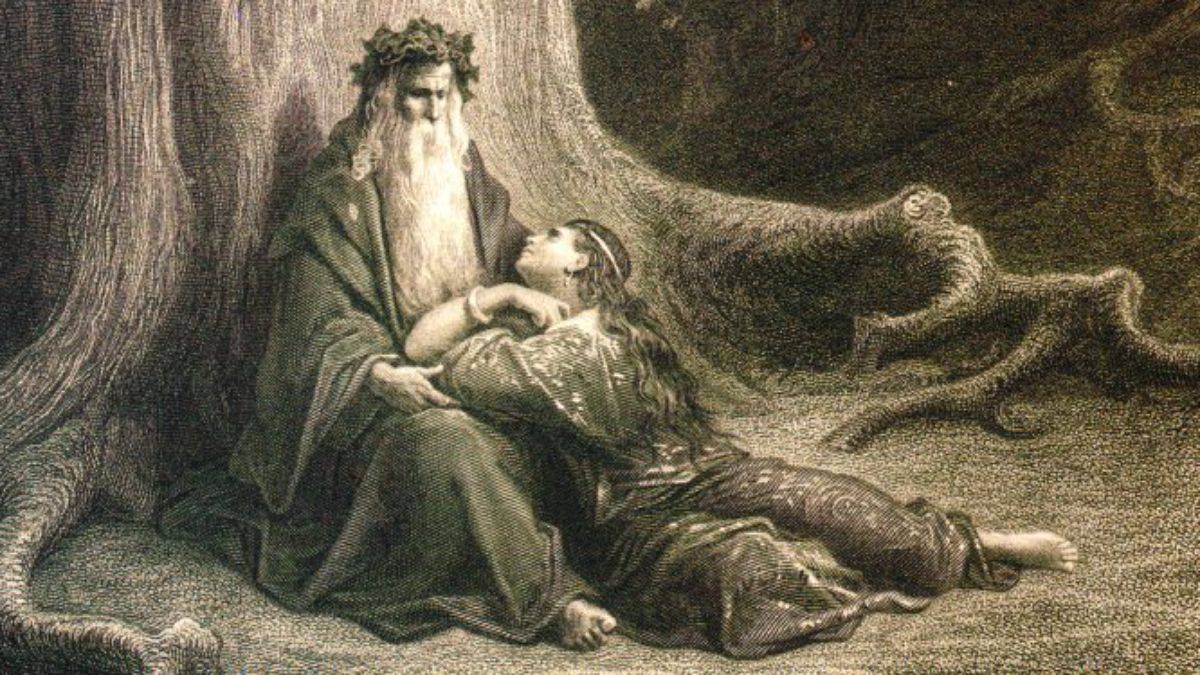

The figure we know today as Merlin (c. 540–c. 618) was never called by this name during his lifetime. The man who serves as the historical basis for Merlin was known as Myrddin. Sometimes he is given the name Myrddin Wyllt (Myrddin the Wild) or Merlinus Caledonensis (Merlin of Caledonia or Scotland) by later writers. Geoffrey of Monmouth is the first to give Myrddin the name Merlin, which derives from Norman English, most likely because the name Myrddin sounded too close to the French merde, which means excrement. For the sake of clarity I will refer to the man we know as Merlin by this given name, as that is how most would identify him. Information about Merlin (also called Lailoken) is found in Jocelyn’s Life of St. Kentigern, written in the twelfth century. Jocelyn portrays Merlin as a foil for his hero Kentigern, who is the patron saint and founder of the see of Glasgow. Jocelyn makes Merlin out to be little more than a court jester, a “foolish man” who entertains by “loud laughter, foolish words, and gestures.”

Ardrey convincingly argues that Merlin-Lailoken was a Druidic bard who was learned in the art of storytelling and stargazing. Ardrey uses various sources to establish that Merlin was the son of a Celtic chief named Morken, as well as that Merlin had a twin sister named Languoreth, wife of Rhydderch Hael, King of Strathclyde. Both Merlin and Languoreth are said to have been born in Cadzow c. 540, which is modern-day Hamilton in Scotland. Merlin’s madness is said to come about as a result of the Battle of Arderydd (c. 573) in the Annales Cambriae (Welsh Chronicles). Ardrey contends that Merlin’s flight into the wilderness was not due to lunacy, but because he had become a political and social outcast from fighting for the wrong side. Merlin was allied to Gwenddolau ap Ceidio, who ruled the region of what is now southwest Scotland against the Scottish people of Strathclyde and Dál Riata.1

Merlin’s side lost what is now known as the Battle of Arderydd to an upstart young military leader named Arthur mac Aedan (more on him in a bit), and Gwenddolau was killed in battle.2 Ardrey convincingly argues that madness did not drive Merlin into self-imposed exile, but rather his having become a social and political outcast, through his opposing his own people and his brother-in-law and future King Rhydderch in battle. Merlin’s exile in the wilderness lasted from 573 after the Battle of Arderydd until approximately 580 when Tutgual, Rhydderch’s father, died. Merlin’s time in exile in the Caledonian forest would be an incredibly difficult time. He had imprudently picked the wrong side in battle and found himself alienated from his family. Tradition is that Merlin’s sister Languoreth is finally able to persuade him to return from exile upon the accession of her husband Rhydderch as King of Strathclyde. Ardrey cites “The Dialogue Between Myrddin and His Sister Gwenddydd” from the Red Book of Hergest, which is derived from a medieval Welsh poem conjecturing the conversation between Merlin and Languoreth that led to Merlin’s rehabilitation back into society.

Ardrey entirely dismisses the tradition that Merlin converted to Christianity upon his return to civilization by Mungo Kentigern – the aforementioned bishop of Glasgow – but Ardrey’s argument is not compelling. Basically Ardrey accuses later Christian authors of concocting this story as propaganda, yet this makes little sense, as Christian authors such as Jocelyn of Furness were inclined to disparage Merlin in order to paint his contemporary Mungo in a better light. Why then should Jocelyn or others have reported a false conversion story? The story of the conversion of Merlin to Christianity is quite ancient, and is commemorated in stained glass at the ancient Stobo Kirk in Scotland.

Merlin spent out his years following his re-entry into society in his hometown of Partick, a village in modern-day Glasgow. Ardrey notes a reference by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Vita Merlini suggesting that the tale of Merlin building Stonehenge is actually a reference to the construction of a major observatory on what is now called Ardery Street in Partick. Per this argument, Ardery is a reference to the Battle of Arderydd which began Merlin’s exile. This is then tied to Merlin’s residence in his hometown upon his rehabilitation. Geoffrey mentions the many windows and rooms of the “Stonehenge” that was built by Merlin, and Ardrey attributes this to the similarity in function between Merlin’s observatory and Stonehenge, since both were used for examining the cosmos. Ardrey argues that Merlin’s observatory in Partick morphed into Stonehenge as his legend migrated south from Scotland to England and Wales. Finally, Ardrey ends with Merlin’s death in approximately 618, which Ardrey contends was by assassination in Drumelzier, which he locates near modern Dunipace in Scotland. The legend of Merlin grew out of his staunch opposition to the Anglo-Saxon invasion threatening the existence of Celtic Britain.

Arthur

The legend of King Arthur remains one of the most compelling narratives in the canon of European folklore. Arthur embodies all of the virtues of chivalry, knighthood, courtly romance, royal justice, and valor. In many ways Arthur stands in stark contrast to our age of decadence and degeneracy. For years I have studied the legend of King Arthur in the hopes of discovering a historical antecedent to the legend in medieval Wales and England. I have discovered the answer I was seeking in Ardrey’s book. Ardrey makes a compelling case that the legend of King Arthur emerged out of the exploits of a warrior prince named Arthur mac Aedan (c. 559–c. 596).3 Legends such as the Sword in the Stone, Excalibur, the Round Table, and Arthur’s death in battle and burial on the Isle of Avalon have their roots in this historical figure. The most impressive evidence that Ardrey presents, and perhaps his most unique contribution to the research in Arthurian lore, is his identification of Arthur mac Aedan with the twelve battles of Nennius.

First, there is the question of Arthur’s parentage and ancestry. The legendary Arthur is said to be the son of a man called Uther Pendragon, king of all Britain, and a woman known as Igraine, while her husband Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall, is away fighting in battle. Gorlois dies and Igraine agrees to give Arthur to the custody of Merlin, who then fosters him to be raised by Sir Ector. Ardrey considers almost all of this as fanciful legend, but he does believe that Uther Pendragon is a historical person. Interestingly, Ardrey maintains that Uther Pendragon is not a proper name but rather a descriptive title. The Pendragons, or Dragon Chiefs, were active in the Celtic resistance against the Anglo-Saxon invaders. The first Pendragon was a man named Emrys, more commonly known as Ambrosius Aurelianus. Emrys was a late-fifth-century warlord who was possibly of Roman-British extraction. Emrys is mentioned by early historians such as Gildas in his De Excidio et Conquestu Brittaniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain), as well as by Nennius in his Historia Brittonum. Geoffrey of Monmouth makes him to be the brother of Uther Pendragon and the uncle of Arthur. This is obviously made up by Geoffrey, but it’s not impossible for there to be a familial connection since both Emrys and Arthur are said to descend from noble British families.

The identity of Emrys as Pendragon is historically sound. What then are we to make of Uther Pendragon, Arthur’s purported father? Ardrey’s solution is intriguing. Ardrey suggests that Uther Pendragon is not a name, but merely a descriptive title. The word Uther is said to derive from antiquated Scottish spelling of the word other. Ardrey cites the Chambers English Dictionary, which provides “uther” as an alternative spelling of the word other. Ardrey also cites the Oxford English Dictionary, which gives the specific Scottish spelling of the same word as “uthyre.” It seems entirely reasonable to believe that Geoffrey of Monmouth was reading sources about the uther (other) Pendragon, and he mistakenly interpreted this as a proper name, as opposed to a title given to a warlord who succeeded Emrys as Pendragon. The man whom Ardrey identifies is Gwenddolau ap Ceidio, the general allied with Merlin who was killed at the Battle of Arderydd. Ardrey reasons that as Gwenddolau was the lieutenant of Emrys, he must have been his successor as Pendragon. After seeing the evidence, I agree that Uther Pendragon is a real historical person, but I disagree with Ardrey about his identity.

I agree with Ardrey that it is possible that Uther Pendragon is not Arthur’s father, but I find his identification of Gwenddolau as Uther to be a bit of a stretch. It seems unlikely that later historians would simply invent the relationship of Uther Pendragon to Arthur if the only relationship between these men in actual history was their opposition at a battle in which the purported father was killed by the son either directly or indirectly. Another reason Ardrey’s explanation is unconvincing is that while there seems to be little known about the Pendragons, I cannot find a source listing Gwenddolau among their number. A better candidate for Uther Pendragon is Maelgwyn of Gwynedd, described by Gildas as the “dragon of the island.” Maelgwyn was a renowned warrior and a regional over-king of northern Wales. While it is clearly an exaggeration by later historians and writers, such as Geoffrey of Monmouth or Sir Thomas Malory, to describe Uther Pendragon as though he were king of all Britain, the designation of Uther as an over-king seems to fit Maelgwyn better than it does Gwenddolau.

Also interesting is that Maelgwyn has two children recorded in ancient genealogies. A son named Rhun Hir succeeded him, and he also had a daughter named Eurgain. Is it possible that she is related to the Igraine or Igerna who is said to be the mother of legendary Arthur?4 This possibility is also intriguing given that Eurgain is said to have married Elidyr Mwynfawr of Strathclyde. Ardrey suggests that Aedan took a British woman as his second wife after the death of his first wife,5 and that this woman was most likely from the kingdom of Strathclyde in modern Scotland, due to Aedan’s alliance with Strathclyde. It is at least possible that Aedan’s unnamed second wife was from the family of Eurgain, which would make Arthur a possible great-grandson of Maelgwyn (or Uther Pendragon). The fact that later writers described Arthur as Uther Pendragon’s son would be akin to Jesus being referred to as “the son of David” and the “son of Abraham” in the Gospels (as in Matthew 1:1). Obviously, much of this is conjectural and nothing can be stated for certain on the topic of sixth-century genealogies.

Arthur mac Aedan’s father was a man named Áedán mac Gabráin, King of the Scottish Kingdom of Dál Riata.6 Dál Riata was a kingdom founded by Gaels from Ulster in Northern Ireland. As such, the Scots of Dál Riata spoke Q-Celtic Gaelic as opposed to the Britons and Picts, who spoke P-Celtic. (The difference between these Indo-European dialects is the origin of the expression “mind your Ps and Qs.”) The Scottish kingdom of Dál Riata was founded by Arthur’s great-great-grandfather, Fergus Mor Mac Erc, upon his invasion of Argyll. Arthur’s father Aedan was raised in the region of Manau and was the son of a Pictish woman and a Scottish royal father, according to Ardrey. Ardrey suggests that Arthur’s mother was Aedan’s British wife, as opposed to his Pictish wife. He reasons that Aedan’s son Gartnait was made king of the Miathi Picts after Arthur’s victory (c. 584) due to the supposition that Aedan’s son Gartnait (who was given a Pictish rather than British name) must have been the son of the Pictish princess Domelch, since this would lend to his legitimacy as a ruler of the Picts. It might have seemed natural for Arthur to have been made a ruler over territory he conquered, but Gartnait was given this territory due to his connections to the Picts. By contrast, Arthur would lead the Strathclyde Britons in battle during the Great Angle War of the 580s, which suggests that his mother was a Briton from Strathclyde.

Many historians dismiss such stories as Arthur drawing a magical sword from a stone or wielding the mighty Excalibur as pure fiction, but Ardrey makes a compelling case that Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone are rooted in actual history. Ardrey maintains that Arthur’s father Aedan was crowned as the King of Scots c. 574 after the Battle of Arderydd in the capital of Dál Riata called Dunadd. In this coronation ceremony, Aedan would have placed his foot in a specially carved footprint on the hillside and would have sat upon the Stone of Destiny brought to Scotland by his Irish ancestors. Ardrey suggests that Arthur was Aedan’s tanist, or heir apparent, after his valor in the Battle of Arderydd. As such Arthur would have had a role to play in his father’s coronation ceremony. Arthur would have placed his foot in the footprint carved into the summit of Dunadd, drawn a ceremonial sword, and brandished it in the four directions of the compass. Later writers such as Sir Thomas Malory would have read of Arthur’s taking a ceremonial stone from the summit of Dunadd, and provided a fanciful explanation of what had actually transpired.7

Excalibur was said to be a magical sword given to Arthur after the sword drawn from the stone was broken. Ardrey argues that the sword drawn from the stone actually was Excalibur, although no contemporary of Arthur would have called the sword by that name. Excalibur was a special ceremonial coronation sword used by the Scots. Geoffrey of Monmouth refers to Arthur’s sword as Caliburn or Caliburnus in Latin. Later the Norman-French writer Wace called this sword Excalibur. Ardrey proposes that this name means “the sword out of Caledonia and Hibernia,” which were the ancient names of Scotland and Ireland, respectively. This strongly points to Arthur being a figure from the Scottish kingdom of Dál Riata whose ancestors migrated to Scotland from Ireland and brought their coronation symbols and regalia along with them. It seems entirely plausible that Excalibur was a ceremonial sword brought to Scotland from Ireland, and that the name of this sword was later contracted to include the ancient names of both lands.

Ardrey also discusses Arthur’s marriage to Guinevere and his inheritance of the Round Table. Ardrey conjectures that Arthur traveled to Ireland with his father Aedan after the Battle of Arderydd in 573 to attend a council of rulers at Drumceatt. Aedan and Arthur then returned to Scotland c. 576, at which time Arthur likely married. The name of Arthur’s wife, Guinevere, is descriptive and roughly means “exceedingly beautiful.” Sir Thomas Malory suggests that Arthur was given the Round Table by Guinevere’s father as a wedding present. According to Ardrey, Guinevere was a Pictish princess from Manau. This would have helped reaffirm Arthur’s family’s position in Manau, where Aedan was raised east of Dál Riata. Ardrey offers The King’s Knot at Stirling Castle Rock as the location of the Round Table. The Round Table was not a table that all sat around in order to establish equality, but a round earthwork. A prominent chieftain would sit in the center and others would be seated around him in order of rank. The remains of The King’s Knot have been restored and can be viewed at Stirling Castle even to this day! I was surprised to find that the legend of the Round Table associated with Stirling is quite strong.

Béroul, a twelfth-century Norman poet, places the Round Table at Stirling in his Romance of Tristan. A squire called Perensis is sent by Tristan to King Arthur: “He inquired for news of the king and learned that he was at Stirling. Fair Yseut’s [Isolde’s] squire went along the road which led in that direction. He asked a shepherd who was playing a reed-pipe: ‘Where is your king?’ ‘Sir,’ said he, ‘he is seated on his throne. You will see the Round Table which turns like the world; his household sits around it.”8 Froisart was a secretary to Queen Philippa of England, and he wrote in his Oeuvres in 1365 of a visit to Stirling. He states that he was told that Stirling was once the castle of King Arthur and that the Round Table was located there.

Scottish poet John Barbour writes in The Brus (The Bruce) c. 1377 of King Edward’s escape from Stirling Castle after the Battle of Bannockburn: “And beneuth the castell went thai sone/Rycht be the Rond Table away…/And towart Lythkow…/Beneath the castle [Stirling] they soon went/Right by the Round Table away…/And toward Linlithgow.” William of Worcester stated in 1478, “King Arthur kept the Round Table at Stirling Castle.” Sir David Lindsay, a sixteenth-century Scottish poet, wrote, “Adew, fair Snawdoun [Stirling], with thy towris hie,/Thy Chapell-royal, park, and Tabyll Round.” It is particularly compelling that these references to the Round Table being located at Stirling Castle are reported by medieval sources from England and Normandy in addition to Scotland, especially in light of Welsh and English writers’ attempts to place Arthur in the south of Britain as opposed to the north.

Given the prominence that Stirling Castle and The King’s Knot must have played in Arthur’s court, it would be tempting to identify Stirling as Camelot, Arthur’s fabled capital. Ardrey argues that Camelot was actually considerably to the west of Stirling, in Arthur’s ancestral homeland of Dál Riata. Ardrey states that Dunadd, the hill fort serving as the site of the Sword in the Stone incident, was the ceremonial capital of Dál Riata. The administrative capital was located nearby at Dunardry,9 which derives from the Scots Gaelic Dun-ArdRigh, meaning “castle of the High King.” Ardrey suggests that Camelot is descriptive of the land encompassing both Dunadd and Dunardry. Ardrey surmises that Camelot is likely a French variation on the Gaelic Cam Loth. Cam is stated to mean “twisted” or “crooked,” and loth is said to mean “marsh,” which combine to mean “crooked marsh.” Ardrey states that this fits the description of the land between Dunadd and Dunardry. The marshland between these two hillforts would is connected by the winding River Add through the Great Moss to the Sound of Jura. This seems to match the picturesque and highly romanticized portrait that later writers imagined when they depicted Camelot with its natural beauty and ancient architectural marvels.

Arthur’s Military Career

This brings us to what has cemented Arthur’s place in legend: his reputed martial prowess. The ninth-century Welsh monk Nennius provides a list of twelve battles that Arthur won in succession. This list has become a riddle that Arthurian scholars have sought to solve for generations. Ardrey argues that many of these scholars have stumbled over Nennius’s list because they are committed to placing Arthur in the south of Britain in the countries of England or Wales. Ardrey makes a compelling case that the battles of Arthur should instead be located in modern Scotland in the late sixth century. In order to make this chronology work Ardrey advises ignoring the dates provided in the Welsh Annals for the dates of the Battles of Badon and Camlann. The Annals date the Battle of Badon to the year 516 and the Battle of Camlann to 537. There are two reasons why these dates seem implausible. First, the Battle of Badon is the twelfth battle listed by Nennius in which Arthur was victorious before being killed at Camlann. A 21-year gap between these final two battles of Arthur’s illustrious career seems inexplicable. Such a gap would be a considerable time period between major battles under the command of a general, even by today’s standards. Secondly, the Annals list the date of the Battle of Arderydd as 573, and provides one of the earliest references to Merlin as having gone mad (fled into the forest) after this battle. Arthur and Merlin have always been considered contemporaries in any iteration of the legends of Arthur, and Merlin is frequently portrayed as being considerably older than Arthur. This is impossible if Arthur dies in 537 well in advance of the Battle of Arderydd in 573. On the strength of these considerations, Ardrey advises us to ignore the dates given for the Battles of Badon and Camlann, suggesting that these were dated to the early sixth century to fill in gaps.

The Battle of Arderydd is not listed by Nennius as one of Arthur’s battles, and this is likely because it occurred prior to Arthur’s command of his father’s armies. It is very likely that Arthur fought with distinction, and that the battle was renamed for Arthur in the generations after his passing. The context of Arthur’s first battle was in a Scottish civil war fought between his father’s supporters and other relatives who vied for the throne of Dál Riata. Shortly after being crowned King of the Scots, Aedan departed for what has become known as the Battle of Delgon in 574, a major victory recorded in the Annals of Tigernach. He left Arthur behind in the capital of Dunadd-Dunardry (Camelot). Aedan emerged victorious, and shortly after this time Arthur achieved his first major victory at the battle that Nennius said was “at the mouth of the river called Glein.” Ardrey suggests that Glein was not a major battle, but a series of skirmishes fought in the many river crossings and glens of Argyll between opponents of Aedan fleeing the Battle of Delgon and forces led by Arthur, Aedan’s son.

Next we come to the second, third, fourth, and fifth battles on Nennius’s list, fought on the river “called the Dubglas [Douglas] which is in the country of Linnuis.” On these battles W.F. Skene wrote, “There are many rivers and rivulets of this name in Scotland; but none could be said to be ‘in regione Linnuis,’ except two rivers—the Upper and Lower Douglas, which fall into Loch Lomond, the one through Glen Douglas, the other at Inveruglas, and are both in the district of the Lennox, the Linnuis of Nennius.”10 Ardrey states that the area north of the Clyde estuary is called Lindum in a map from second-century geographer Ptolemy. Ardrey suggests that the word Lindum is derived from the Irish Gaelic word lind, which means “pool.” This later became linn in Scottish Gaelic, and suggests that this later became the Latin word Linnuis and was applied to the area south and west of Loch Lomond before receiving its present name of Lennox. This is the only place that matches the combination of Douglas and Linnuis/Lennox.

Ardrey suggests that the Miathi Picts took advantage of the Scottish civil war to invade Dál Riata on its eastern border near Loch Lomond. This series of battles likely took place over an extended period of time in which Arthur was dispatched to the eastern marches of Dál Riata in order to defend the border against Pictish invaders. Ardrey notes that Arthur’s presence in this region is etched into the landscape itself:

Halfway up the west bank of the loch, five miles north of Glen Douglas and the River Douglas, a pass runs west from Loch Lomond, through Glen Croe, over the well-named height called the Rest and Be Thankful, through Glen Kinglas to Loch Fyne and the heartlands of Argyll. The eastern end of this strategically vital approach is dominated by a mountain that, even today, is called Ben Arthur. This is a perfect place for any man charged with commanding an army on the Dál Riata-Pictland border to have had his headquarters. . . . To invade Dál Riata the Picts would have had to cross Douglas—specifically they would have had to traverse the pass commanded by the hill Ben Arthur, because Douglas and Ben Arthur lay between Dál Riata and Pictland.11

At the base of these rivers Douglas, Arthur successfully defended Dál Riata from invasion through four straight battles, or as Ardrey conjectures, four consecutive campaigning seasons. Ardrey suggests that these battles took place during the mid- to late-570s.

The sixth battle of Arthur is said to have been fought “on the river Bassas,” historians have had difficulty locating. Ardrey suggests that this battle was fought in Pictish territory in 584 after Arthur had successfully staved off the Pictish invasion in four successive campaigns. The place name Bassas has passed into obscurity, but Ardrey suggests that Bassas is a variant spelling known to Nennius centuries after the Roman occupation in Britain. Ardrey contends that Bassas is derived from the name of a third-century Roman emperor whose birth name was Lucius Septimius Bassianus, and who is more commonly known by the moniker Caracalla. Caracalla spent time in what is now northern England and Scotland during his father Septimius Severus’s campaign of conquest from 208 to 210. Ardrey suggests that the battle on the river Bassas is a reference to a battle fought between Arthur’s Scots and the Miathi Picts at the old Roman fort at Carpow situated at the confluence of the Tay and Earn rivers near modern Perth in Scotland.

Ardrey maintains that the river Earn may have been known as the Bassianus due to the construction of a fixed bridge during Caracalla’s reign. Caracalla received this nickname during his tenure in Britain, and it may literally mean “lover of the Caledonians,” from the word cara meaning “dear to” and calla as a contraction of “Caledonian.” This may have come about because he ended his father’s brutal campaign for conquest after his father died in 211. Caracalla may have earned this nickname after brokering piece with the native Pictish tribes and ultimately leaving for the continent. Interestingly enough, Geoffrey of Monmouth lists Caracalla as a king of Britain under his birth name Bassianus. This lends further credence to the idea that Carpow and the Rivers Tay and Earn retained his name in local geography for centuries afterward, and was known as Bassas during the time of Nennius. After this conquest of Pictland and Pictish King Bridei mac Maelchon was killed, Arthur’s older half-brother Gartnait (the son of Aedan’s Pictish wife Domelch) was made king of the Picts.

The Great Angle War

These battles certainly would have cemented Arthur’s reputation as a military leader among his contemporaries, but Arthur’s achievements during the Great Angle War beginning in the mid-580s established him as a legend in the centuries following his death. Before the Great Angle War, Arthur’s battles had helped to secure his father’s position as King of the Scots of Dál Riata, defeat Pictish invaders, and ultimately overthrow a hostile Pictish king. During the Great Angle War Arthur became a military leader over a confederation of several Celtic kingdoms to stand united against the Anglo-Saxon invasion. This invasion commenced with the advance of the Angle King Hussa north from his base in Bernicia around 585. Hussa invaded the British kingdom of the Gododdin and marched north towards modern Edinburgh.

Instead of marching east to join ranks with the beleaguered Gododdin at Edinburgh to meet the invading Angle army, Arthur marched his men south from Manau to Peebles before turning east in order to flank the main body of the Angle army. Ardrey suggests that Arthur used tactics similar to Confederate General Magruder at the Battle of the Wilderness in which he staved off a numerically superior Union attack in 1862. Arthur’s men were spread wide and thin throughout the Caledonian forest and used hit-and-run guerrilla tactics to avoid major engagements. This gave the Angles the impression that Arthur’s army was far more numerous. The Angles were slowed by Arthur’s constant harassment long enough for reinforcements from Strathclyde to arrive. This is the basis for the seventh battle in Nennius’s list, the “Battle of the Caledonian Wood.” After these skirmishes the Angle army was still intact and formidable, but had been slowed from its initial pace in which the Angles threatened to easily overrun the British kingdoms in modern Scotland. As a result of this campaign Arthur was given command of the combined British forces. Nennius writes, “Then Arthur fought against them in those days, together with the kings of the British, but he was their leader in battle.”12 Ardrey suggests that Merlin may well have advocated for the leadership of Arthur over the allied armies at this point, which contributed to the association between Merlin and Arthur in later literature.

The eighth battle of Nennius’s list is said to have taken place at Guinnion Fort. Ardrey places this battle at the old Roman fort near Stow in Wedale, only a short day’s march from the aforementioned Caledonian woods. W.F. Skene notes that Guinnion Fort was associated with the church at Wedale in Stow. The Vatican Recension version of Nennius contains additional information confirming this location: “[Arthur] took with him the image of St. Mary, the fragments of which are still preserved in great veneration at Wedale, in English Wodale, in Latin Vallis-doloris. Wodale is a village in the province of Lodonesia, but now of the jurisdiction of the bishop of St. Andrew’s, of Scotland, six miles on the west of that heretofore noble and eminent monastery of Meilros.”13 It is obviously highly unlikely that Arthur carried an image of the Virgin Mary with him during the battle, but this does confirm the location of this battle at Stow in Lothian or Lodonesia, as this manuscript reads, as well as the proper distance from Stow to Melrose. The reference to the image of Mary likely was added by a cleric to gain fame for an image of Mary that existed at the church near the battle. Ardrey suggests that the name Guinnion is derived from the Celtic gwyn which means “blessed,” given by Christians who named the area for the Virgin Mary.

After Arthur successfully drove the Angle army back at Guinnion Fort, the Angle army retreated south and regrouped. Here both opposing armies faced each other in Nennius’s ninth battle, fought “in the city of the Legion.” Ardrey locates this at Trimontium, the capital of Scotland during the Roman occupation in the first and second centuries. Trimontium is located where the Gala Water joins the River Tweed near Melrose. This was a major victory for Arthur’s Britons and an equally devastating defeat for the Angles, who suffered massive casualties. Arthur did not relent and sought to draw the Angles into battle once more. The tenth battle on Nennius’s list was fought “on the river Tribuit.” The name Tribuit is obscure and has caused difficulty for historians in identifying the battle’s location. Ardrey notes that the Vatican Recension of Nennius’s Historia has the word Trevoit as opposed to Tribuit. This allows Ardrey to easily identify the site of the tenth battle as the River Teviot, located ten miles south of Trimontium and continuing a straight geographic line through battles seven through nine.

Ardrey suggests that after these series of defeats by the Britons under the command of Arthur, the Angles allied themselves with the Picts. Perhaps a plan was agreed upon to divide up conquered Scottish territory, with land conquered by the Scots in earlier generations returning to the Picts, and the land of other British kingdoms in the modern Scottish lowlands being taken by the Angles. Ardrey argues that the Angles sailed north into Pictish territory and there launched an attack on the Scots. They met Arthur’s army at Beregonium, or what Nennius called Breguoin, at modern Benderloch. This was located at the site of an old Roman mountain fortress which Arthur’s ancestor Fergus captured from the Picts, located about forty miles north of the Scottish capital of Dunadd-Dunardry (Camelot). The combined Anglo-Pictish forces were comprised of infantry who marched west from Carpow, the site of the Battle of Bassas, the sixth in Nennius’s list. The Anglo-Pictish forces were then reinforced by ships that sailed to Beregonium-Benderloch and anchored in the Ardmucknish Bay, and were forced to retreat back to their ships after being repulsed by Arthur’s forces.

Ardrey surmises that the Anglo-Pictish forces were mostly spent after this defeat. Arthur likely might have thought that the escaping Angles and Picts were sailing back home, but they instead sailed south forty miles to the unprotected Scottish capital. Conquest was now beyond the realm of possibility, as the Anglo-Pictish forces were too depleted after their recent defeat. The goal of this invasion was plunder before the forces of Arthur could be alerted and mobilized. The Scots living in the area fled to the protection of the twin fortresses of Dunadd and Dunardry while the land around this area was plundered. Word came to Arthur, who then immediately marched his army south to rescue the besieged Scots. Ardrey suggests that the reference to three days and three nights in the Welsh Annals may be symbolic, but it also may represent the time it took Arthur to move his army south during which the Angles and Picts plundered without opposition. Arthur marched his men south to the land surrounding the Scottish capital, referred to as Badden.14 Arthur then routed the Angles and Picts and ended their brief raid upon the inhabitants who lived there.

Arthur’s Death and Burial on the Isle of Avalon

Arthur is said to have been killed or at least mortally wounded at the Battle of Camlann, fought between the forces of Arthur and his nephew Mordred. Ardrey accepts Geoffrey of Monmouth’s attestation of Mordred’s identity as the son of Arthur’s sister Anna (or Morgause by other sources) through her second marriage to Lot of the Lothians. Mordred is thought to have been a Gododdin Briton who rose up against relatives. This makes Mordred the half-brother of the faithful Arthurian knights Sirs Gawain, Gareth, and Gaheris. This battle is dated by Ardrey c. 596, years after the conclusion of the Great Angle War. Ardrey cites Adomnán, a Christian writer who states that Aedan’s army (led by Arthur) fought a battle against his old foes, the Miathi Picts at Circenn-Carpow, near Nennius’s sixth battle at the river Bassas. Arthur was victorious, but his army suffered devastating losses in this Pyrrhic victory. It was at this point that Mordred decided to launch his offensive. Mordred led his army against Scotland and met Arthur’s army at what has become known as the Battle of Camlann, which Ardrey locates at the Camelon region of Falkirk. Arthur, the great warrior and defender of his kingdom, was finally felled as his beleaguered army was overmatched. Mordred is said to have died here as well, so Arthur is able to claim a sort of victory even in his death.

After Arthur’s death, Sir Thomas Malory relates that Sir Bedevere throws Excalibur into a lake in order to return Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake who originally gave the sword to Arthur. Ardrey rejects the supernatural elements present in Malory, and suggests that one of Arthur’s knights likely did throw his sword into a lake in accordance with an ancient Celtic ritual, though this would not have been the ceremonial sword Excalibur that Arthur wielded at his coronation decades prior.

Finally there is the mystery of the Isle of Avalon. Avalon has been identified by many as Glastonbury, but this identification cannot withstand even mild scrutiny. Glastonbury is not an island, and there is no good reason to believe that it was an island in Arthur’s day. Avalon is placed by Geoffrey in “the western seas,” and this description makes Glastonbury impossible. Ardrey offers a compelling case for Iona, and island off the western coast of Dál Riata where many Scottish and Irish kings were buried. Ardrey notes that St. Columba, Arthur’s distant relative, may have been present at Arthur’s burial, and that this may have taken place at the ancient Abbey church located there. Iona is noted for its natural beauty and tranquility, and matches Geoffrey’s description of an island paradise.

Arthur’s victory in the Great Angle War pushed the Angles out of modern Scotland and caused their retreat back to their coastal heartland, what is now East Anglia. They would remain there for thirty years before staging another campaign, this time going south rather than north. This campaign would be successful and result in the establishment of England (Angle-land).

Arthur is remembered in European legend because of his heroic stand against a powerful invading army. Arthur mac Aedan altered the course of history through his courage, knowledge of warfare, and leadership. Adam Ardrey has done a compelling job of locating the historical Merlin and Arthur in what is now Scotland. These men gained their legendary status due to their efforts in keeping hostile invaders out of their homelands. Without Arthur’s success there would have been no Scotland and likely no Wales or Ireland, only a Greater England.

Arthur is chief among Europe’s “sleeping heroes”: kings or warriors thought to be waiting to return to the throne and rescue their people from certain disaster. The legendary Arthur rests on the Isle of Avalon, where he waits for his opportunity to rescue his people once more. I find the concept of the sleeping hero fascinating. While there is no question that this tradition is rooted in folklore, it also seems to be grounded in the Christian understanding of death as a falling asleep (Matt. 9:24; Mk. 5:39; Lk. 8:52). The legends of the kings in the mountains serve as a reminder that one day “the Lord cometh with ten thousands of his saints” (Jude 14). The legend of King Arthur developed because history remembers kindly those who fight to protect their kindred and people. The legend of King Arthur has developed and become embellished over time, but the legend is tied to actual history, as Adam Ardrey demonstrates. King Arthur, his knights, and their contemporaries have inspired generations of European poets and writers, from Taliesin and Aneiren of the Flowing Verse to Sir Walter Scott and Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Today, the whole of the European people face an existential threat to our existence, as Arthur and his knights did in their day. Today we face an invasion of hostile foreigners bent on our destruction, and the stakes are so much higher in our day. Arthur valiantly fought and led men into battle to establish the place of the Scots in Britain; today we must fight to secure the very existence of the entire white race and the civilization our ancestors produced and sustained. Like Arthur and his knights, we must meet our challenges with courage, fortitude, and valor. Someday we will ride alongside Arthur and the whole host of sleeping heroes who await their chance to reclaim their homelands from hostile invasion once and for all. Until that time we are tasked with doing our part today to secure our people’s existence for future generations. Perhaps the years to come will see the emergence of a new hero, a worthy successor of Arthur, the Once and Future King.

Footnotes

- This map of sixth-century Britain provides a general layout of the kingdoms that existed at that time. ↩

- Nineteenth-century historian W.F. Skene located the Battle of Arderydd near modern Arthuret. ↩

- Technically his name would have been spelled Artúr mac Aedan, but I will continue to refer to him as Arthur for the sake of simplicity. ↩

- Some suggest that Eurgain, the daughter of Maelgwyn, is the St. Eurgain for whom an old church in northern Wales is named. She is said to also be a niece of St. Asaph. This potentially lends further credence to an Arthurian connection as Geoffrey of Monmouth; the admittedly fanciful chronicler of Arthur was the bishop of St. Asaph in north Wales. ↩

- Aedan’s first wife is thought to be Domelch, a Pictish princess. Interestingly enough, this genealogy states that the father of Domelch was Maelgwyn of Gwynedd, whom I have proposed as a possible historical basis for Uther Pendragon. I find this doubtful, and it seems to have been asserted based upon the similarity of the names Maelgwyn and Maelchon. ↩

- Ardrey suggests that the identification of Tintagel Castle in Cornwall as the birthplace of Arthur is entirely fanciful, and that this detail to the Arthurian legend was added by Geoffrey of Monmouth because his patron’s brother was the owner of Tintagel Castle at the time. This is a sound explanation, but it is likely that Tintagel was a fortress during the days of Arthur, and that Arthur may have been related to the Cornish Britons there through his Welsh and British ancestors. ↩

- Ardrey is insistent that Arthur was never a king proper, and this is true since he never lived to succeed his father, but later generations likely considered Arthur a king due to his role as his father’s heir apparent, similar to the early coronation of Henry the Young King during the lifetime of his father Henry II of England. ↩

- Béroul, The Romance of Tristan (London: Penguin Books, 1970). Cited in Ardrey, Finding Arthur, pg. 139. ↩

- Dunardry became the historic seat of Clan MacTavish. ↩

- The Four Ancient Books of Wales, translated by W.F. Skene (Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas, 1868), chapter IV, 52. Cited in Ardrey, Finding Arthur, pg. 208. ↩

- Ardrey, Finding Arthur, pg. 209-210. ↩

- Nennius, Historia Brittonum, cited in Ardrey, Finding Arthur, pg. 230. ↩

- D.N. Dumville, Historia Brittonum iii: The Vatican Recension (Cambridge, 1985); and History of the Britons (Kessinger Publishing’s Rare Reprints: no date), 32. Cited in Ardrey, Finding Arthur, pg. 233. ↩

- The word “Camelot” refers to the winding River Add. This source confirms that the land north of Dunardry and south of Dunadd was called Badden/Boadan. ↩

| Tweet |

|

|

|